Ian Woo Interviewed by Tony Godfrey

In his studio 20th March 2023

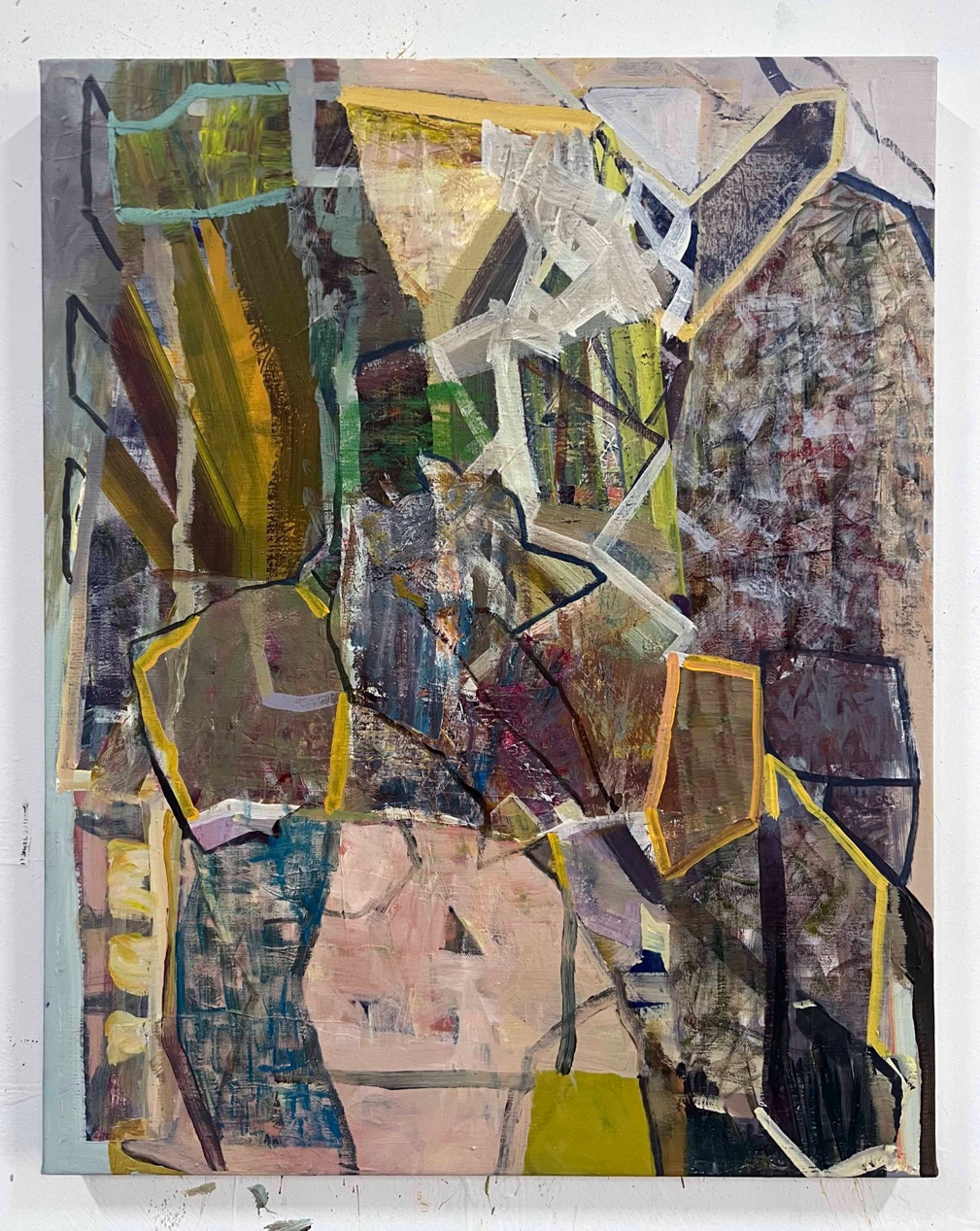

Ian Woo, Chromatic Pulse React, 2023

Ian Woo, Chromatic Pulse React, 2023

TG: How was the pandemic for you?

IW: It was great! I got to work in the studio even more than I would’ve liked. Time was a little bit more suspended. That was great for the artist. I am not crazy about spending too long a time in the studio, but I have the ability to take my time. Anyway, usually when I work I can only work two hours on a painting and then I would have to stop because I would either make the wrong decisions or I would just overwork it.

TG: So, it’s your natural game: a football match with an extra half hour of added time – two hours.

IW: Also. it’s the eyes. My eyes get tired after that length of time and are likely to make mis-judgments.

TG: OK, so after that two hours you stop. What do you do? Have a cigarette and a beer? Read a book or go home?

IW: Well, I don’t smoke. I do like a drink, but I never drink when I work.

TG: But seriously, when you’ve reached the end of that two-hour period and you realized you’re not one hundred percent anymore, do you go home, or you just rest for a while? How do you get back in the mood?

IW: I could rest here, have tea or some water. I would have some tonic water in all probability and then I’d just turn on some music and check my e-mails.

TG: The last time you turned on the music, what did you listen to?

IW: It was ECM records. It’s a German label, it was one of the new Nordic jazz bands that have appeared by a guy named Mats Eilertson. I wanted to listen to some ambient music. Sometimes I randomly choose something that is recommended by Spotify. But I don’t work with music on: I just listen to it after I have stopped working. It affects me a bit too much, so I try not to do that.

TG: So, you basically paint in silence, apart from the sound of the MRT trains whooshing by outside.

IW: Which is great, I think the sound of the train is quite nice, yeah! I have water sounds because of the air conditioner. I quite like that sound – that air-conditioned bubbling.

TG: How long will your break normally be?

IW: I can take a break for thirty minutes and then get back to work again but usually I will work on a different piece if I have time, I will spend about four hours in the studio and then I have to get out. I don’t think I should stay in the studio for too long.

In my work the composition changes quite a bit. I work on the floor sometimes; I work on the wall sometimes. It varies a lot: sometimes I’m doing a very calculated move; sometimes it’s not a calculated move. For example, in the most recent painting I drew these lines around some very intuitive mark that I made. They were very loose graphic marks but then the next day I came in and added the white line. Almost as if I’m framing those marks.

TG: So, this is a little bit of an improvisation followed by reining the horses in. I think that’s something consistent in your work, things seem chaotic but are often tidied up.

IW: Sometimes a structure needs to be clarified or coloured in. Or the colour has to be flat, without too many gradations. I think decisions like that become quite important in my work. The idea of a dialogue or juxtaposition of opposites is important.

TG: What is the relationship between the big one you are working on and the smaller paintings. Are they related?

IW: Yes, always related.

TG: In what way?

IW: Related in the way I set up the forms, in relationship to how they connect and when I say how the forms connect it deals with the idea of trying to find a kind of system or logic between form and space. How they come together and fall apart — like an organism in its environment.

There is always this idea of various compartments in the painting that have activities going on, but they impact each other. It’s as if they each have an energy that impacts the others. Structures change, and they could be doing this… [pointing at Chromatice Pulse React – please note, the image shown is of this painting when finished.]

TG: …the network of white lines to the right of the orange.

IW: …could become the orange, so obviously the temperature has changed. And then maybe this has become this…

TG: …the white jagged lines, yes? Is white the colour you often finish a painting with?

IW: Maybe. Possibly. When you think about that highlight, in a sense maybe I’m a renaissance painter where the highlights of a still life are usually added towards the end.

TG: Yes, it’s funny in way: the drawing comes at the end because if I look at that white hexagonal line. It’s tying it all together.

IW: Actually, in my painting, there’s a lot of drawing: I may draw first and then I will paint, but I actually you’re right, I actually draw sometimes at the end.

TG: I think that’s consistent. Apart from these larger paintings I can see five small, four very small drawings or watercolours pinned to the wall. Are they finished or are they ongoing?

IW: Finished. These are things that I look at and sometimes I will use in my painting, but they are not sketches. They are finished works, but I might use ideas from them in the main work.

TG: Are they after the paintings or before the paintings?

IW: Neither. I think they function separately because they are done in the study room in my house. I bring them here sometimes to pin up and just have a look at.

TG: There is different quality in them to the paintings. It looks as if there are more accidents. Is there a higher failure rate with them?

IW: Yes, because you can’t work too much on them. The white in them comes from the paper. It is so easy to cover them up by using gouache white as layering. The gouache white is a different white from the white of the paper. That’s a combination that I quite like. It’s the material of the paper that makes me do different things.

TG: So just going back to the pandemic period. You teach several days a week at Lasalle College for the art. Did Lasalle stopped teaching for a whole year?

IW: No, we continued, but a lot of things were online.

TG: On Zoom. Was that weird?

IW: It was weird. we tried our best to teach on Zoom but we pushed for studio meetups. The physical meetups are very important because otherwise you can’t see the work, and there’s nothing to talk about.

TG: You can’t do it on Zoom.

IW: I can do a supervision on an essay on Zoom but that’s about it.

TG: Let’s talk about this painting. Does this have a title? the big painting.

IW: It’s called “An Island in Monet“

Ian Woo, An island in Monet – Acrylic on linen 2020 (Photograph by Wong Jing Wei)

TG: The little scrubby blue bit in the middle with the orange circle around it, is that the island?

IW: Maybe, but I think what matters is the whole, the overall quality of depth and that tone which is something that I have seen in a Monet painting of his Water Lily Pond. It’s that colour which is half gold and half green. This, specifically, is from my experience of visiting and seeing the Monet works on paper that were in Setouchi, Naoshima Islands. It was an island that had this enclosed space with these watercolours installed. It was like seeing pictures in space framed within frames. Like repeated Monets appearing within frames. This is a kind of a homage or memory of that experience.

If you look at the colour it is quite dark and perhaps that’s down to the thing that is tropical about it. It’s almost as if my response is coming from within a shadow I experienced on the island. Enclosed within a shadow. This painting was one that I took out after giving up on it several years ago. It was a very old painting that I took out and I had a go at it and I manage to find a plot.

TG: What did you have to change?

IW: I reworked the whole thing.

TG: If I saw a photograph of the old painting, I wouldn’t recognize it.

IW: Yes, you wouldn’t recognize it. But I think it has a history. I think it started with this. An island within an island within an island. It has got multiple enclosures here. It’s quite complex and contradictory.

TG: Very contradictory. Now I can see the connection to Monet but it’s to do with colours, isn’t it?

IW: Yes, it is, and atmosphere as well. It’s almost a reflection, a softer reflection.

TG: It’s not the only time in your painting that there is a window of some sort.

IW: There is always some kind of a frame.

TG: In the 18th century that may have been be a gap between trees or other repoussoirs.

IW: The only difference is that the information of these frames is not rational in the gravitational sense. It always gets cropped off and then something happens below it that has no relationship to what’s on the top. Like here. Between this.

TG: This is the bit between the hexagon and what I called the island. Is this a painting you’re especially happy with?

IW: It’s actually a melancholic painting.

TG: Was there any reason for that?

IW: No, or perhaps it was the COVID. It is kind of a dark work. Which is not for everyone, but that’s alright. We all have some darkness. When I finished it, I wasn’t even sure that I should be showing this work but I said, “Well, I’ve already completed it and I think there is something there that I’m proud about and it’s dark. So be it.”

TG: On the far left is a very lyrical passage. There is really dark jagged line in the bottom right corner. It’s quite brutal in a way. There are areas that are very dark, or a very dark blue and they look as they have been cut out and collaged on. It’s a painting with a lot of contradictions really.

IW: Yes, you’re right. Lyrical and then contrasted with a cut out with something that’s quite physical. Constructed. But there is also a bit of architecture you know.

TG: Compared to Monet there is a lot of architectonics in it, like scaffolding. Monet always took the scaffolding out.

IW: I guess it’s a space I live in

TG: Perhaps that comes from Singapore: all that the scaffolding and the structures. Just training in from the airport to here just reminded me of how incredibly urban this is, how many buildings there are, not higgledy-piggledy, but yet not on a grid. It seems rigid and it seems totally arbitrary. Why is this road curved here? and not there? I guess it’s because the streets mainly grew along roads between the villagers.

IW: Yes, but also now if you look at Singapore, they tend to create wider, but minimal empty spaces. And that combines with the new train stations that they are building. It’s like a constant transition. Singapore is almost in constant transition.

Ian Woo Studio 20.3.23

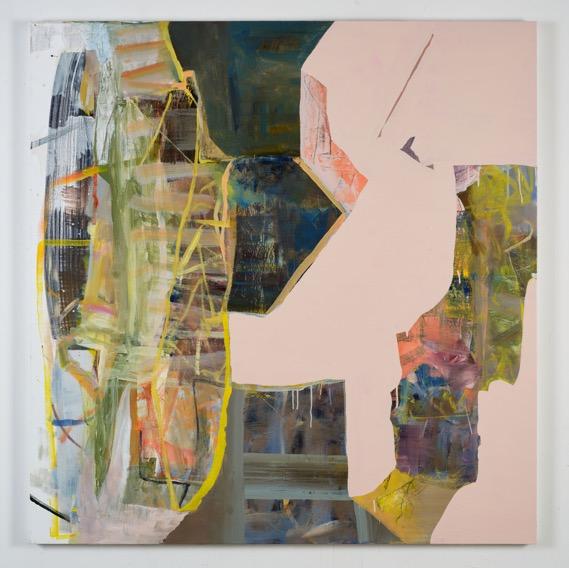

TG: The painting with the large expanses of pink this was made when?

IW: 2023, two weeks ago. I can’t figure out a title yet.

Ian Woo, Pink lady – Acrylic on linen, 2023 (Photograph by Wong Jing Wei)

TG: The pink instantly reminds me of how sometimes Willem de Kooning would put a female body in a painting.

IW: You see it as a body?

TG: Yes, a white woman’s body.

IW: It took me three applications of pink to arrive at this. I had to find the right tonality.

TG: If I compare this with paintings you made a few years ago they were more consciously holistic, much more harmonised. Now that there’s often much more disruption. Is that something that came with or accelerated with the pandemic?

IW: I don’t know actually: I think the mark making changed quite a bit. I feel that the way I divide the spaces is also a little bit different from before; there are more dramatic shapes in the current work that I am making

TG: During the pandemic and even afterwards, we didn’t travel, we didn’t see much in reality – in the flesh, so to speak, anymore, especially art. We are much more reliant on what we see only the web. Has that had an effect on you? Can one tell?

IW: I guess making paintings is like traveling, making art is like a way to travel. I walked a lot during the pandemic; I spend a lot of time walking in the beach. I walked for an hour or more than an hour.

TG: You’re quite close to the sea where you live on. Is there a beach?

IW: Yes, I would walk there almost every day. Now I’m walking less along the beach, but I think I walk more within the city.

TG: You don’t have a dog that makes you exercise?

IW: No, I don’t have that. I don’t have a dog. I’m a cat person.

This painting, Gateway, obviously has been made during my walks or rather afterwards. To me this painting has a connection to the rhythm of walking.

TG: These vertical and horizontal strips?

IW: Yes

TG: How many sessions did this painting take?

IW: I was working on it for probably about four months, but not every day. I would work on it twice in a week and then leave it alone and then come back to it. And you can see there is a similar kind of front-back, back-front, front-back, you know. the framing devices are creating this possible front and back illusion and it multiplies – like mirrors reflecting mirrors.

TG: They remind me of how Degas pastels, where often he found that the paper wasn’t quite big enough so he added another bit. You had that feeling in the Monet Island painting. It looks the same as Monet, but with a bit added to the left, a bit added on top. This one obviously had bit added to top right and bottom.

IW: And it’s called Gateway. As if something’s been opening up like a gate -opening up.

TG: It looks like a Japanese hieroglyph.

IW: Some of the young audiences that were here said that it looks like a hashtag, like a hashtag meme. You can tell that this is a 2021 painting in the sense that the lockdowns is ending: the sense of hope of things opening up.

TG: Even though you said it was a great time to paint, the painting you produced are quite melancholic. This one certainly is!

Ian Woo, Gateway, Acrylic on linen (Photograph by STPI Creative Workshop and Gallery)

IW: Yes, but when I say “great”, it doesn’t mean that I produced happy works.

TG: Did you know anyone that died in the pandemic?

IW: Fortunately, no, but I think of the musicians that passed away I know. A lot of jazz musicians passed away. It was all very mysterious back then because you didn’t know what was going to happen next. Maybe things are going to be like that forever. Maybe that’s why there’s kind of a melancholic reflection about life, but when you see this painting you can sense that – oh yes -maybe there’s something else, maybe things will open up soon.

TG: It’s much more jazzy; it’s much more vibrant.

IW: I think these two paintings present a good closed and open situation.

TG: You mentioned Japan: is that a big influence on you?

IW: Yes, I do like Japan a lot, the culture, the food, and art. Singaporeans like to travel to Japan, because it is a safe country… except for the earthquakes. It’s quite easy to travel around and obviously they have beautiful work there. I mean historically they have always had beautiful work. It’s always quite inspiring. Last year I was teaching there in Musashino University. I teach there every two years. And it was great, teaching the painting students there. They are all very good painters.

TG: Technically

IW: And very sensitive with the touch, they can do whatever they wanted to do. But it was great hanging out with them because they also understand the complexities of making paintings. So, the dialogue is always enriching.

TG: By your natural instinct, do you feel closer to Japanese artist than say an Indonesian artist?

IW: Actually, I don’t think I’m close to either of the two countries, I know artists there, but I don’t think I know them that well.

I love Indonesia, for example the history of the music that they have with the Gamelan. The sound is beautiful. It is something that is so distinctive to our region here. I think the way Indonesians deal with colour is fantastic. Sometimes I use yellow, and I do think about Indonesia, because they use yellow quite a bit. I think about my time in Jogja. There’s something about the heat. Yellow is also like the colour of gold for the Chinese.

TG: It’s a very, more consciously tropical than you are in Singapore.

IW: They are also very chaotic, which I quite like.

TG: It’s a good change from Singapore.

IW: In Japan, I like the way they organize things, they are very creatively organized. So that too is quite a positive influence to have. Just to pick the best of each. But In terms of knowing the artist, I don’t think I know them well enough; I mean I know Heri Dono but I do not know him well enough. He’s great to talk to.

TG: Yeah, he’s a raconteur.

IW: But there’s always only so much you can know because you’re not part of that culture. I know my Singaporean artist much better because we understand the problems we all have, the limits of what can happen here.

I think we talk about Japan and Indonesia quite a bit because, these are old cultures. So, my Singaporean artist friends and I need to travel and see works of art, we have to see the real paintings of the western canon, we need to see them at least a couple of times and that’s when we are learning. And then you go travel to Japan to see the prints. Indonesia to watch the performances of the Barong dance. There are have good ones and the other not so good ones, you know. You watch a good one and then you’d be very inspired. So, I think traveling is so important for a Singaporean artist.

TG: One difficulty in Singapore, is that there are not a lot of collectors of contemporary art.

IW: Well, there is only so many collectors and the taste-wise, I think is quite hard to convince certain collectors about abstraction. I still feel there’s a lot of misunderstanding about abstraction. They would like to hear a story. But sometimes there’s no story in a painting. I mean I’ve told you a couple of stories here, but in a sense they are not really stories.

TG: They are not essential to understand the painting. The painting discloses itself in different ways.

IW: Good abstraction does that. However, I’ve learned that I have to think about ways to communicate the painting in a way that is simple enough but yet doesn’t water down the complexity of the work. So, it’s a combination of talking about how it was being made and also the kind of inspiration that the painting comes from. That’s one way to get around it. but frankly the folks that buy my work, they never ask for an explanation. I think things are changing, I think a lot of younger people here are learning to use their intuition to look at work.

TG: So, breaking with the whole ethos in Singapore of being very rational.

IW: Yeah exactly. I can be rational in the way I talk about the work. I can. and it’s fine.

TG: Your paintings always have this move between intuition and then reorganizing. Throwing a rope around this area, putting a hexagon in, tidying up making it clearer adding a little emphasis.

IW: And then also looking at the work as if I’m a stranger who has not seen it, which is really hard.

TG: When you come into the studio, what’s the first thing you do? Sit down or just look at the painting or…

IW: I actually look at the painting on the wall without the lights on.

TG: Right, just natural light.

IW: Yeah, in darkness sometimes. And if the painting can pop in the darkness I say “Okay maybe there’s something there. Then I turn on the lights and I look at it again and that’s the surprise.”

TG: I recall that Rothko always wanted his paintings to be underlit so they would emerge slowly as the viewer recalibrated their eyes.

IW: Which is what I think is very important. When I first saw Rothko at the Tate, the old Tate, the light was dim. I liked it.

TG: They’re gloomy.

IW: Melancholic.

TG: Have you been to the Rothko Chapel in Houston?

IW: I would like to go one day.

TG: I have, and it was a very bizarre experience, I sat there and there were people in there planning a wedding and eventually the museum-people told them, “I’m sorry, you can’t do this. Out you go.” What a terrible place to have a wedding! This is a funeral chapel. It’s very sombre, very dark, very beautiful, absolutely melancholic. Great for funeral services, but definitely not for weddings, if you want to have your wedding there, you misunderstand the paintings now. This is a man in terrible health, a family breakdown, drinking heavily, not in a good frame of mind. It’s much more of an installation than the room in the Tate

IW: It’s constructing the atmosphere; that is the art. There was a piece of music that was composed for the Rothko chapel.

TG: Yes, Rothko Chapel by Morton Feldmann.

IW: Well, the two of them, they connect very well because it comes from a Jewish folk melody, I think.

TG: That’s right. It’s a nice piece of music. Very sombre.

IW: Lyrical as well.

Small paintings, 2020-21, 2019, 2007

TG: I have just realized, right above this, on the right, there are very small paintings. The one on the right must be older.

IW: Yes. It’s figurative, it’s a house.

TG: Why did you put them up there?

IW: I recently renovated the studio, and they have to put this pipe here because of the aircon duct. So, I realized, “Hey, it looks like a ledge I can put something on”, so I did.

TG: Did you always have the aircon on?

IW: Yeah, I always have. It’s too cold. Sometimes I won’t turn on the aircon when I paint. Sometimes it’s raining and its cool enough outside.

I realise, by the way, you have used COVID as a pivot in this interview.

TG: Yes, because I’m meeting people here in Singapore for the first time in several years. This the first time I’ve been in your studio since COVID. There’s catching up to do, but, also it did change things. You’re not the only person that said “it was great” because you got so much more studio time. Cecilia Allemani who curated the last Venice Biennale said art had become more personal, more intimate because of COVID.

[At this point Ian went to collect some food he had ordered – Pad Thai and Chicken Wings – and we ate it. He put some different paintings on the wall.]

TG: You have set out two large and ten quite small paintings that you did in 2018? Why are they on wood?

IW: Esplanade which contains a theatre and concert hall asked me to create some artworks for that long corridor that runs from the MRT Station to the theatre. The point was to create things for the wall that the public would look at it or not look at it. Either they’re rushing to the theatre or too busy with other things. Not so many people stop to look hard. It’s a really long wall. I made a whole series of wooden structure objects that are painted on. Why wood? It’s because they wanted something a bit hardier to withstand the public space, because people might touch it. They wanted to put a ring fence in front of it and I said “No”. Because if they touch it then that’s just too bad, it’s my problem. I told them that “It’s not going to work if you put a ringfence in it”. So, I produced these works and sure enough, a couple of people did touch them but that’s fine.

TG: Were they irreparably damaged?

IW: No, it was okay. Probably some finger marks on it.

TG: So, these ten small paintings are extracts of a bigger body. Did you see them working like sculptures in space?

IW: I see them as more like pictorial objects. The point was to get you to walk along past them and just to have a glimpse of them. Because that’s what I thought the rushing travellers would have with the little time they have. It could not function like a serious painting in a museum, they were objects that are painted on.

Ian Woo, Emotional Things – As displayed in the Esplanade Tunnel 2018 (Photograph by Ken Cheong)

Emotional Things, 2018, as seen 20.3.23 in the studio. (The large painted object above was also part of the Esplanade installation.)

TG: But they do have moods. They’re quite moody! If I look here, there’s one which is a blue monochrome and another one rather like a pink sky with a white sun and white stars on it.

IW: You’re right, in a sense that they are about the phenomena of everyday life as someone walking on earth. When you walk the sun hits you, and in the night, the temperature changes. You see different kinds of things that change through the time of your journey. It’s really about that kind of experience.

TG: They are sketches, aren’t they?

IW: Well, no, but they were done very quickly. Once I felt that they looked right I’d just leave them. They are quite minimal in a sense because I wanted them to be like very quick snippets of experiences.

TG: Here in your studio, you have placed them close together in a row. That is I guess how you originally installed them.

IW: Indeed, it depends on the space and on what’s around them. I’ve shown them in another gallery where I put them quite close as well. They can actually be reshuffled and placed further apart if needed. If you look closely, the width of these boards varies in length, but the height stays the same

TG: Does that matter? They are like off cuts.

IW: I think this creates the idea of irregularity in life.

TG: So, the ten could easily be extended to twenty or thirty?

IW: In theory, yes, but I think this ten will be it. If I made another series, it would be based on a separate idea.

TG: You could not recover the mood again.

IW: The mood has gone: it was 2018, a certain period and feeling when I made this in.

TG. They, and the title reminds me of Franz West, who made Passtucke emotional sculptures which you could handle.

IW: Oh really? I should look at those works. It’s a very simple idea. They are objects but by painting them, it injects within each of them a form of emotion. I think I got this idea from how we like to put objects in our house so as to project our sense of taste, which to me actually equates to a kind of sentiment.

TG: Did painting on wooden panel felt different from painting on canvas?

IW: Well, number one, I realized that I was not making pictures here: I was making objects that will participate once they come into a space – almost like actresses and actors. Waiting to be deployed in an opera that has not been staged yet.

TG: So, the blue one is probably one of your sopranos, isn’t it?

IW: (Chuckles). That’s a good reading actually. Why is blue a soprano?

TG: I have to think about that, I mean you could argue that it should a bass.

IW: Bass will be Jesus, isn’t it?

TG: What voice would the green painting have?

IW: Definitely not a bass, probably a mid-tone

TG: A baritone or tenor.

IW: Yes, I think it is a tenor. I think the soprano is the light one.

TG: The pink one

IW: Yes, the pink one

TG: I think you’re right. Though of course in reality, a good singer could sing all ten. Because these are ranges of emotions not of notes. So, in a way they are colour paintings but deep down they’re not: they’re about capturing a few moods. The relationship of a viewer to them is different because they’re not normal paintings. They’re asking to be discussed, negotiated.

IW: They are also negotiated in a sense that they look almost incomplete individually, and you need to see them as a whole to experience it… Actually, if you see them as a whole, they never really resolve, you have to resolve it.

TG: Yeah, they remind me of Raul de Keyser who made small, unresolvable paintings.

IW: I like his work. His paintings would often be as small as these, but complex too.

TG: When you went out to get some food, I looked behind me and realized It’s setup for full musical performance. There’s keyboard, drum set, guitar, are you having concerts with yourself?

IW: I have a band comes in to play sometimes.

TG: How often?

IW: Not as often as I would like, because they keep traveling, but we are meeting at the end of the month. Do you know Angie Seah the performance artist? She is the singer and there’s Aya Sekine, the keyboard player but she’s traveling as well.

TG: They are all artists?

IW: The drummer Jun is a sound, audio engineer. Aya is a professional jazz pianist.

TG: So, you the four of you just come in and jam for an hour.

IW: Yeah, and we make tunes, we have a YouTube video, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pwingjytwk0) The band is called Qianpima. Which means a thousand horses in Chinese.

Qianpima in the studio 2020 (Image courtesy of Aya Sekine)

Qianpima in the studio 2020 (Image courtesy of Aya Sekine)

TG: Are you all Chinese?

IW: Singaporean Chinese, except Aya who is Japanese. We can practice for two hours and stop. You remember I played bass guitar for a performance with you? You did a talk that was all improvised.

TG: It worked well I wish it had been recorded. We should do something again like that.

IW: Anytime, just call me. By the way, do you know the piece of music by Gavin Bryars – Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet?

TG: Yes, It’s beautiful. It’s just an old man singing on the street.

IW: One of the most sublime experiences I had.

TG: Endlessly repeated with variations.

IW: I would like to use repetitions a bit more in my paintings in the future.

Added after my visit to Singapore in July 2023

Ian Woo, Earthquake Interiors, 1998 and Knees and Toes, 1998, as shown at Fost Gallery 2023.

Ian Woo, Earthquake Interiors, 1998 and Knees and Toes, 1998, as shown at Fost Gallery 2023.

Ian Woo, Finger Food, 1998

Ian Woo, Finger Food, 1998

TG. We have talked at such length about your recent work that I do not think we can talk in detail as I had planned to about your earlier work. But as you have an exhibition of paintings made twenty-five years ago currently on show at Fost gallery, perhaps we can talk a little about a couple of paintings in that show. For example, Finger Food. I can see what the title suggests and how it applies to these paintings as being like things laid flat on a tray, but they also remind me very much of the ideogram paintings that Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb were making in the Nineteen-Forties. It is a more numinous reference than canapés. Do you see a connection?

IW: The answer to the ideogram reference is yes but I never thought of it explicitly. Afterall, all my invented gestural forms refer to me searching for images that are ambiguous as memory. My encounter with ideograms could be seen in relation to how early Chinese or Egyptian characters / picture words were developed to communicate a kind of language. It’s a basic human need to invent images to communicate. Art to me is invention, curiosity and continuity.

TG: The notion of the numinous in Rothko is that, something deeper or more spiritual underlies and appears, however subtly, through the painting. Paradoxically, three table paintings of the late Nineties have something of that, but are also quite pop-arty in their suggestion of objects – and there are the titles, of course! Finger Food, Vanilla Days, Sunny-side up. These paintings have less suggestion of landscape and landscape space than most of your paintings. Am I barking up the wring tree or trees? Were they a deliberate attempt to get away from a space that suggested landscape?

IW: Well, they are based on the interiority of the study room which is where I made them. Can spirituality exist in these private domestic enclosures? Of course. Painting in a small room, asking questions about existence, living with a new family and the future.

TG: How different was your working method back then? Did you have a smaller studio then?

IW: I painted in my study room which had one empty wall just the size of these paintings so that only when I shut the door, I was able to see them without furniture interruptions. I painted fast and often in between house chores. Early morning before work or late at night after work.

TG: As a writer I must admit to enjoying re-editing old writings. There is always something one could say better or that one understands better – or thinks one does! But there comes a point where the work becomes too distant, somehow outside one self. I could re-edit my book The Story of Contemporary Art from 2020, even maybe my Painting Today book from 2009, but I couldn’t re-edit my Conceptual Art book from 1998. It belongs to a different time, a different world. And as for my first book which come out in 1986 it looks to me now as if it was written by another person, which in a way it was – a much younger me. How do you think about these tabletop paintings now? Are they something you could return to? Even paint some extra ones?

IW: You are right that time has passed. It’s a different context of desire and need. But with these table top paintings. it is about a subject matter that is timeless so, “Yes!” I could return to them. But for now, I am interested in the flatness of the space in them. So, I have actually started employing them again in my new work, to see how it belongs in the present tense.

TG: Thanks Ian, it has been great talking about these works and your studio practice. There is much we haven’t gotten to talk about: how you became an artist, your time in UK and Spain, and almost all of the work you made before the pandemic. Maybe we can cover that another time.

.

Ian Woo Interviewed by Tony Godfrey

In his studio 20th March 2023

Ian Woo, Chromatic Pulse React, 2023

TG: How was the pandemic for you?

IW: It was great! I got to work in the studio even more than I would’ve liked. Time was a little bit more suspended. That was great for the artist. I am not crazy about spending too long a time in the studio, but I have the ability to take my time. Anyway, usually when I work I can only work two hours on a painting and then I would have to stop because I would either make the wrong decisions or I would just overwork it.

TG: So, it’s your natural game: a football match with an extra half hour of added time – two hours.

IW: Also. it’s the eyes. My eyes get tired after that length of time and are likely to make mis-judgments.

TG: OK, so after that two hours you stop. What do you do? Have a cigarette and a beer? Read a book or go home?

IW: Well, I don’t smoke. I do like a drink, but I never drink when I work.

TG: But seriously, when you’ve reached the end of that two-hour period and you realized you’re not one hundred percent anymore, do you go home, or you just rest for a while? How do you get back in the mood?

IW: I could rest here, have tea or some water. I would have some tonic water in all probability and then I’d just turn on some music and check my e-mails.

TG: The last time you turned on the music, what did you listen to?

IW: It was ECM records. It’s a German label, it was one of the new Nordic jazz bands that have appeared by a guy named Mats Eilertson. I wanted to listen to some ambient music. Sometimes I randomly choose something that is recommended by Spotify. But I don’t work with music on: I just listen to it after I have stopped working. It affects me a bit too much, so I try not to do that.

TG: So, you basically paint in silence, apart from the sound of the MRT trains whooshing by outside.

IW: Which is great, I think the sound of the train is quite nice, yeah! I have water sounds because of the air conditioner. I quite like that sound – that air-conditioned bubbling.

TG: How long will your break normally be?

IW: I can take a break for thirty minutes and then get back to work again but usually I will work on a different piece if I have time, I will spend about four hours in the studio and then I have to get out. I don’t think I should stay in the studio for too long.

In my work the composition changes quite a bit. I work on the floor sometimes; I work on the wall sometimes. It varies a lot: sometimes I’m doing a very calculated move; sometimes it’s not a calculated move. For example, in the most recent painting I drew these lines around some very intuitive mark that I made. They were very loose graphic marks but then the next day I came in and added the white line. Almost as if I’m framing those marks.

TG: So, this is a little bit of an improvisation followed by reining the horses in. I think that’s something consistent in your work, things seem chaotic but are often tidied up.

IW: Sometimes a structure needs to be clarified or coloured in. Or the colour has to be flat, without too many gradations. I think decisions like that become quite important in my work. The idea of a dialogue or juxtaposition of opposites is important.

TG: What is the relationship between the big one you are working on and the smaller paintings. Are they related?

IW: Yes, always related.

TG: In what way?

IW: Related in the way I set up the forms, in relationship to how they connect and when I say how the forms connect it deals with the idea of trying to find a kind of system or logic between form and space. How they come together and fall apart — like an organism in its environment.

There is always this idea of various compartments in the painting that have activities going on, but they impact each other. It’s as if they each have an energy that impacts the others. Structures change, and they could be doing this… [pointing at Chromatice Pulse React – please note, the image shown is of this painting when finished.]

TG: …the network of white lines to the right of the orange.

IW: …could become the orange, so obviously the temperature has changed. And then maybe this has become this…

TG: …the white jagged lines, yes? Is white the colour you often finish a painting with?

IW: Maybe. Possibly. When you think about that highlight, in a sense maybe I’m a renaissance painter where the highlights of a still life are usually added towards the end.

TG: Yes, it’s funny in way: the drawing comes at the end because if I look at that white hexagonal line. It’s tying it all together.

IW: Actually, in my painting, there’s a lot of drawing: I may draw first and then I will paint, but I actually you’re right, I actually draw sometimes at the end.

TG: I think that’s consistent. Apart from these larger paintings I can see five small, four very small drawings or watercolours pinned to the wall. Are they finished or are they ongoing?

IW: Finished. These are things that I look at and sometimes I will use in my painting, but they are not sketches. They are finished works, but I might use ideas from them in the main work.

TG: Are they after the paintings or before the paintings?

IW: Neither. I think they function separately because they are done in the study room in my house. I bring them here sometimes to pin up and just have a look at.

TG: There is different quality in them to the paintings. It looks as if there are more accidents. Is there a higher failure rate with them?

IW: Yes, because you can’t work too much on them. The white in them comes from the paper. It is so easy to cover them up by using gouache white as layering. The gouache white is a different white from the white of the paper. That’s a combination that I quite like. It’s the material of the paper that makes me do different things.

TG: So just going back to the pandemic period. You teach several days a week at Lasalle College for the art. Did Lasalle stopped teaching for a whole year?

IW: No, we continued, but a lot of things were online.

TG: On Zoom. Was that weird?

IW: It was weird. we tried our best to teach on Zoom but we pushed for studio meetups. The physical meetups are very important because otherwise you can’t see the work, and there’s nothing to talk about.

TG: You can’t do it on Zoom.

IW: I can do a supervision on an essay on Zoom but that’s about it.

TG: Let’s talk about this painting. Does this have a title? the big painting.

IW: It’s called “An Island in Monet“

An island in Monet – Acrylic on linen 2020 (Photograph by Wong Jing Wei)

TG: The little scrubby blue bit in the middle with the orange circle around it, is that the island?

IW: Maybe, but I think what matters is the whole, the overall quality of depth and that tone which is something that I have seen in a Monet painting of his Water Lily Pond. It’s that colour which is half gold and half green. This, specifically, is from my experience of visiting and seeing the Monet works on paper that were in Setouchi, Naoshima Islands. It was an island that had this enclosed space with these watercolours installed. It was like seeing pictures in space framed within frames. Like repeated Monets appearing within frames. This is a kind of a homage or memory of that experience.

If you look at the colour it is quite dark and perhaps that’s down to the thing that is tropical about it. It’s almost as if my response is coming from within a shadow I experienced on the island. Enclosed within a shadow. This painting was one that I took out after giving up on it several years ago. It was a very old painting that I took out and I had a go at it and I manage to find a plot.

TG: What did you have to change?

IW: I reworked the whole thing.

TG: If I saw a photograph of the old painting, I wouldn’t recognize it.

IW: Yes, you wouldn’t recognize it. But I think it has a history. I think it started with this. An island within an island within an island. It has got multiple enclosures here. It’s quite complex and contradictory.

TG: Very contradictory. Now I can see the connection to Monet but it’s to do with colours, isn’t it?

IW: Yes, it is, and atmosphere as well. It’s almost a reflection, a softer reflection.

TG: It’s not the only time in your painting that there is a window of some sort.

IW: There is always some kind of a frame.

TG: In the 18th century that may have been be a gap between trees or other repoussoirs.

IW: The only difference is that the information of these frames is not rational in the gravitational sense. It always gets cropped off and then something happens below it that has no relationship to what’s on the top. Like here. Between this.

TG: This is the bit between the hexagon and what I called the island. Is this a painting you’re especially happy with?

IW: It’s actually a melancholic painting.

TG: Was there any reason for that?

IW: No, or perhaps it was the COVID. It is kind of a dark work. Which is not for everyone, but that’s alright. We all have some darkness. When I finished it, I wasn’t even sure that I should be showing this work but I said, “Well, I’ve already completed it and I think there is something there that I’m proud about and it’s dark. So be it.”

TG: On the far left is a very lyrical passage. There is really dark jagged line in the bottom right corner. It’s quite brutal in a way. There are areas that are very dark, or a very dark blue and they look as they have been cut out and collaged on. It’s a painting with a lot of contradictions really.

IW: Yes, you’re right. Lyrical and then contrasted with a cut out with something that’s quite physical. Constructed. But there is also a bit of architecture you know.

TG: Compared to Monet there is a lot of architectonics in it, like scaffolding. Monet always took the scaffolding out.

IW: I guess it’s a space I live in

TG: Perhaps that comes from Singapore: all that the scaffolding and the structures. Just training in from the airport to here just reminded me of how incredibly urban this is, how many buildings there are, not higgledy-piggledy, but yet not on a grid. It seems rigid and it seems totally arbitrary. Why is this road curved here? and not there? I guess it’s because the streets mainly grew along roads between the villagers.

IW: Yes, but also now if you look at Singapore, they tend to create wider, but minimal empty spaces. And that combines with the new train stations that they are building. It’s like a constant transition. Singapore is almost in constant transition.

Ian Woo Studio 20.3.23

TG: The painting with the large expanses of pink this was made when?

IW: 2023, two weeks ago. I can’t figure out a title yet.

Pink lady – Acrylic on linen, 2023 (Photograph by Wong Jing Wei)

TG: The pink instantly reminds me of how sometimes Willem de Kooning would put a female body in a painting.

IW: You see it as a body?

TG: Yes, a white woman’s body.

IW: It took me three applications of pink to arrive at this. I had to find the right tonality.

TG: If I compare this with paintings you made a few years ago they were more consciously holistic, much more harmonised. Now that there’s often much more disruption. Is that something that came with or accelerated with the pandemic?

IW: I don’t know actually: I think the mark making changed quite a bit. I feel that the way I divide the spaces is also a little bit different from before; there are more dramatic shapes in the current work that I am making

TG: During the pandemic and even afterwards, we didn’t travel, we didn’t see much in reality – in the flesh, so to speak, anymore, especially art. We are much more reliant on what we see only the web. Has that had an effect on you? Can one tell?

IW: I guess making paintings is like traveling, making art is like a way to travel. I walked a lot during the pandemic; I spend a lot of time walking in the beach. I walked for an hour or more than an hour.

TG: You’re quite close to the sea where you live on. Is there a beach?

IW: Yes, I would walk there almost every day. Now I’m walking less along the beach, but I think I walk more within the city.

TG: You don’t have a dog that makes you exercise?

IW: No, I don’t have that. I don’t have a dog. I’m a cat person.

This painting, Gateway, obviously has been made during my walks or rather afterwards. To me this painting has a connection to the rhythm of walking.

TG: These vertical and horizontal strips?

IW: Yes

TG: How many sessions did this painting take?

IW: I was working on it for probably about four months, but not every day. I would work on it twice in a week and then leave it alone and then come back to it. And you can see there is a similar kind of front-back, back-front, front-back, you know. the framing devices are creating this possible front and back illusion and it multiplies – like mirrors reflecting mirrors.

TG: They remind me of how Degas pastels, where often he found that the paper wasn’t quite big enough so he added another bit. You had that feeling in the Monet Island painting. It looks the same as Monet, but with a bit added to the left, a bit added on top. This one obviously had bit added to top right and bottom.

IW: And it’s called Gateway. As if something’s been opening up like a gate -opening up.

TG: It looks like a Japanese hieroglyph.

IW: Some of the young audiences that were here said that it looks like a hashtag, like a hashtag meme. You can tell that this is a 2021 painting in the sense that the lockdowns is ending: the sense of hope of things opening up.

TG: Even though you said it was a great time to paint, the painting you produced are quite melancholic. This one certainly is!

Gateway, Acrylic on linen (Photograph by STPI Creative Workshop and Gallery)

IW: Yes, but when I say “great”, it doesn’t mean that I produced happy works.

TG: Did you know anyone that died in the pandemic?

IW: Fortunately, no, but I think of the musicians that passed away I know. A lot of jazz musicians passed away. It was all very mysterious back then because you didn’t know what was going to happen next. Maybe things are going to be like that forever. Maybe that’s why there’s kind of a melancholic reflection about life, but when you see this painting you can sense that – oh yes -maybe there’s something else, maybe things will open up soon.

TG: It’s much more jazzy; it’s much more vibrant.

IW: I think these two paintings present a good closed and open situation.

TG: You mentioned Japan: is that a big influence on you?

IW: Yes, I do like Japan a lot, the culture, the food, and art. Singaporeans like to travel to Japan, because it is a safe country… except for the earthquakes. It’s quite easy to travel around and obviously they have beautiful work there. I mean historically they have always had beautiful work. It’s always quite inspiring. Last year I was teaching there in Musashino University. I teach there every two years. And it was great, teaching the painting students there. They are all very good painters.

TG: Technically

IW: And very sensitive with the touch, they can do whatever they wanted to do. But it was great hanging out with them because they also understand the complexities of making paintings. So, the dialogue is always enriching.

TG: By your natural instinct, do you feel closer to Japanese artist than say an Indonesian artist?

IW: Actually, I don’t think I’m close to either of the two countries, I know artists there, but I don’t think I know them that well.

I love Indonesia, for example the history of the music that they have with the Gamelan. The sound is beautiful. It is something that is so distinctive to our region here. I think the way Indonesians deal with colour is fantastic. Sometimes I use yellow, and I do think about Indonesia, because they use yellow quite a bit. I think about my time in Jogja. There’s something about the heat. Yellow is also like the colour of gold for the Chinese.

TG: It’s a very, more consciously tropical than you are in Singapore.

IW: They are also very chaotic, which I quite like.

TG: It’s a good change from Singapore.

IW: In Japan, I like the way they organize things, they are very creatively organized. So that too is quite a positive influence to have. Just to pick the best of each. But In terms of knowing the artist, I don’t think I know them well enough; I mean I know Heri Dono but I do not know him well enough. He’s great to talk to.

TG: Yeah, he’s a raconteur.

IW: But there’s always only so much you can know because you’re not part of that culture. I know my Singaporean artist much better because we understand the problems we all have, the limits of what can happen here.

I think we talk about Japan and Indonesia quite a bit because, these are old cultures. So, my Singaporean artist friends and I need to travel and see works of art, we have to see the real paintings of the western canon, we need to see them at least a couple of times and that’s when we are learning. And then you go travel to Japan to see the prints. Indonesia to watch the performances of the Barong dance. There are have good ones and the other not so good ones, you know. You watch a good one and then you’d be very inspired. So, I think traveling is so important for a Singaporean artist.

TG: One difficulty in Singapore, is that there are not a lot of collectors of contemporary art.

IW: Well, there is only so many collectors and the taste-wise, I think is quite hard to convince certain collectors about abstraction. I still feel there’s a lot of misunderstanding about abstraction. They would like to hear a story. But sometimes there’s no story in a painting. I mean I’ve told you a couple of stories here, but in a sense they are not really stories.

TG: They are not essential to understand the painting. The painting discloses itself in different ways.

IW: Good abstraction does that. However, I’ve learned that I have to think about ways to communicate the painting in a way that is simple enough but yet doesn’t water down the complexity of the work. So, it’s a combination of talking about how it was being made and also the kind of inspiration that the painting comes from. That’s one way to get around it. but frankly the folks that buy my work, they never ask for an explanation. I think things are changing, I think a lot of younger people here are learning to use their intuition to look at work.

TG: So, breaking with the whole ethos in Singapore of being very rational.

IW: Yeah exactly. I can be rational in the way I talk about the work. I can. and it’s fine.

TG: Your paintings always have this move between intuition and then reorganizing. Throwing a rope around this area, putting a hexagon in, tidying up making it clearer adding a little emphasis.

IW: And then also looking at the work as if I’m a stranger who has not seen it, which is really hard.

TG: When you come into the studio, what’s the first thing you do? Sit down or just look at the painting or…

IW: I actually look at the painting on the wall without the lights on.

TG: Right, just natural light.

IW: Yeah, in darkness sometimes. And if the painting can pop in the darkness I say “Okay maybe there’s something there. Then I turn on the lights and I look at it again and that’s the surprise.”

TG: I recall that Rothko always wanted his paintings to be underlit so they would emerge slowly as the viewer recalibrated their eyes.

IW: Which is what I think is very important. When I first saw Rothko at the Tate, the old Tate, the light was dim. I liked it.

TG: They’re gloomy.

IW: Melancholic.

TG: Have you been to the Rothko Chapel in Houston?

IW: I would like to go one day.

TG: I have, and it was a very bizarre experience, I sat there and there were people in there planning a wedding and eventually the museum-people told them, “I’m sorry, you can’t do this. Out you go.” What a terrible place to have a wedding! This is a funeral chapel. It’s very sombre, very dark, very beautiful, absolutely melancholic. Great for funeral services, but definitely not for weddings, if you want to have your wedding there, you misunderstand the paintings now. This is a man in terrible health, a family breakdown, drinking heavily, not in a good frame of mind. It’s much more of an installation than the room in the Tate

IW: It’s constructing the atmosphere; that is the art. There was a piece of music that was composed for the Rothko chapel.

TG: Yes, Rothko Chapel by Morton Feldmann.

IW: Well, the two of them, they connect very well because it comes from a Jewish folk melody, I think.

TG: That’s right. It’s a nice piece of music. Very sombre.

IW: Lyrical as well.

Small paintings, 2020-21, 2019, 2007

TG: I have just realized, right above this, on the right, there are very small paintings. The one on the right must be older.

IW: Yes. It’s figurative, it’s a house.

TG: Why did you put them up there?

IW: I recently renovated the studio, and they have to put this pipe here because of the aircon duct. So, I realized, “Hey, it looks like a ledge I can put something on”, so I did.

TG: Did you always have the aircon on?

IW: Yeah, I always have. It’s too cold. Sometimes I won’t turn on the aircon when I paint. Sometimes it’s raining and its cool enough outside.

I realise, by the way, you have used COVID as a pivot in this interview.

TG: Yes, because I’m meeting people here in Singapore for the first time in several years. This the first time I’ve been in your studio since COVID. There’s catching up to do, but, also it did change things. You’re not the only person that said “it was great” because you got so much more studio time. Cecilia Allemani who curated the last Venice Biennale said art had become more personal, more intimate because of COVID.

[At this point Ian went to collect some food he had ordered – Pad Thai and Chicken Wings – and we ate it. He put some different paintings on the wall.]

TG: You have set out two large and ten quite small paintings that you did in 2018? Why are they on wood?

IW: Esplanade which contains a theatre and concert hall asked me to create some artworks for that long corridor that runs from the MRT Station to the theatre. The point was to create things for the wall that the public would look at it or not look at it. Either they’re rushing to the theatre or too busy with other things. Not so many people stop to look hard. It’s a really long wall. I made a whole series of wooden structure objects that are painted on. Why wood? It’s because they wanted something a bit hardier to withstand the public space, because people might touch it. They wanted to put a ring fence in front of it and I said “No”. Because if they touch it then that’s just too bad, it’s my problem. I told them that “It’s not going to work if you put a ringfence in it”. So, I produced these works and sure enough, a couple of people did touch them but that’s fine.

TG: Were they irreparably damaged?

IW: No, it was okay. Probably some finger marks on it.

TG: So, these ten small paintings are extracts of a bigger body. Did you see them working like sculptures in space?

IW: I see them as more like pictorial objects. The point was to get you to walk along past them and just to have a glimpse of them. Because that’s what I thought the rushing travellers would have with the little time they have. It could not function like a serious painting in a museum, they were objects that are painted on.

Emotional Things – As displayed in the Esplanade Tunnel 2018 (Photograph by Ken Cheong)

Emotional Things, 2018, as seen 20.3.23 in the studio. (The large painted object above was also part of the Esplanade installation.)

TG: But they do have moods. They’re quite moody! If I look here, there’s one which is a blue monochrome and another one rather like a pink sky with a white sun and white stars on it.

IW: You’re right, in a sense that they are about the phenomena of everyday life as someone walking on earth. When you walk the sun hits you, and in the night, the temperature changes. You see different kinds of things that change through the time of your journey. It’s really about that kind of experience.

TG: They are sketches, aren’t they?

IW: Well, no, but they were done very quickly. Once I felt that they looked right I’d just leave them. They are quite minimal in a sense because I wanted them to be like very quick snippets of experiences.

TG: Here in your studio, you have placed them close together in a row. That is I guess how you originally installed them.

IW: Indeed, it depends on the space and on what’s around them. I’ve shown them in another gallery where I put them quite close as well. They can actually be reshuffled and placed further apart if needed. If you look closely, the width of these boards varies in length, but the height stays the same

TG: Does that matter? They are like off cuts.

IW: I think this creates the idea of irregularity in life.

TG: So, the ten could easily be extended to twenty or thirty?

IW: In theory, yes, but I think this ten will be it. If I made another series, it would be based on a separate idea.

TG: You could not recover the mood again.

IW: The mood has gone: it was 2018, a certain period and feeling when I made this in.

TG. They, and the title reminds me of Franz West, who made Passtucke emotional sculptures which you could handle.

IW: Oh really? I should look at those works. It’s a very simple idea. They are objects but by painting them, it injects within each of them a form of emotion. I think I got this idea from how we like to put objects in our house so as to project our sense of taste, which to me actually equates to a kind of sentiment.

TG: Did painting on wooden panel felt different from painting on canvas?

IW: Well, number one, I realized that I was not making pictures here: I was making objects that will participate once they come into a space – almost like actresses and actors. Waiting to be deployed in an opera that has not been staged yet.

TG: So, the blue one is probably one of your sopranos, isn’t it?

IW: (Chuckles). That’s a good reading actually. Why is blue a soprano?

TG: I have to think about that, I mean you could argue that it should a bass.

IW: Bass will be Jesus, isn’t it?

TG: What voice would the green painting have?

IW: Definitely not a bass, probably a mid-tone

TG: A baritone or tenor.

IW: Yes, I think it is a tenor. I think the soprano is the light one.

TG: The pink one

IW: Yes, the pink one

TG: I think you’re right. Though of course in reality, a good singer could sing all ten. Because these are ranges of emotions not of notes. So, in a way they are colour paintings but deep down they’re not: they’re about capturing a few moods. The relationship of a viewer to them is different because they’re not normal paintings. They’re asking to be discussed, negotiated.

IW: They are also negotiated in a sense that they look almost incomplete individually, and you need to see them as a whole to experience it… Actually, if you see them as a whole, they never really resolve, you have to resolve it.

TG: Yeah, they remind me of Raul de Keyser who made small, unresolvable paintings.

IW: I like his work. His paintings would often be as small as these, but complex too.

TG: When you went out to get some food, I looked behind me and realized It’s setup for full musical performance. There’s keyboard, drum set, guitar, are you having concerts with yourself?

IW: I have a band comes in to play sometimes.

TG: How often?

IW: Not as often as I would like, because they keep traveling, but we are meeting at the end of the month. Do you know Angie Seah the performance artist? She is the singer and there’s Aya Sekine, the keyboard player but she’s traveling as well.

TG: They are all artists?

IW: The drummer Jun is a sound, audio engineer. Aya is a professional jazz pianist.

TG: So, you the four of you just come in and jam for an hour.

IW: Yeah, and we make tunes, we have a YouTube video, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pwingjytwk0) The band is called Qianpima. Which means a thousand horses in Chinese.

Qianpima in the studio 2020 (Image courtesy of Aya Sekine)

TG: Are you all Chinese?

IW: Singaporean Chinese, except Aya who is Japanese. We can practice for two hours and stop. You remember I played bass guitar for a performance with you? You did a talk that was all improvised.

TG: It worked well I wish it had been recorded. We should do something again like that.

IW: Anytime, just call me. By the way, do you know the piece of music by Gavin Bryars – Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet?

TG: Yes, It’s beautiful. It’s just an old man singing on the street.

IW: One of the most sublime experiences I had.

TG: Endlessly repeated with variations.

IW: I would like to use repetitions a bit more in my paintings in the future.

Added after my visit to Singapore in July 2023

Earthquake Interiors, 1998 and Knees and Toes, 1998, as shown at Fost Gallery 2023.

Earthquake Interiors, 1998 and Knees and Toes, 1998, as shown at Fost Gallery 2023.

Finger Food, 1998

TG. We have talked at such length about your recent work that I do not think we can talk in detail as I had planned to about your earlier work. But as you have an exhibition of paintings made twenty-five years ago currently on show at Fost gallery, perhaps we can talk a little about a couple of paintings in that show. For example, Finger Food. I can see what the title suggests and how it applies to these paintings as being like things laid flat on a tray, but they also remind me very much of the ideogram paintings that Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb were making in the Nineteen-Forties. It is a more numinous reference than canapés. Do you see a connection?

IW: The answer to the ideogram reference is yes but I never thought of it explicitly. Afterall, all my invented gestural forms refer to me searching for images that are ambiguous as memory. My encounter with ideograms could be seen in relation to how early Chinese or Egyptian characters / picture words were developed to communicate a kind of language. It’s a basic human need to invent images to communicate. Art to me is invention, curiosity and continuity.

TG: The notion of the numinous in Rothko is that, something deeper or more spiritual underlies and appears, however subtly, through the painting. Paradoxically, three table paintings of the late Nineties have something of that, but are also quite pop-arty in their suggestion of objects – and there are the titles, of course! Finger Food, Vanilla Days, Sunny-side up. These paintings have less suggestion of landscape and landscape space than most of your paintings. Am I barking up the wring tree or trees? Were they a deliberate attempt to get away from a space that suggested landscape?

IW: Well, they are based on the interiority of the study room which is where I made them. Can spirituality exist in these private domestic enclosures? Of course. Painting in a small room, asking questions about existence, living with a new family and the future.

TG: How different was your working method back then? Did you have a smaller studio then?

IW: I painted in my study room which had one empty wall just the size of these paintings so that only when I shut the door, I was able to see them without furniture interruptions. I painted fast and often in between house chores. Early morning before work or late at night after work.

TG: As a writer I must admit to enjoying re-editing old writings. There is always something one could say better or that one understands better – or thinks one does! But there comes a point where the work becomes too distant, somehow outside one self. I could re-edit my book The Story of Contemporary Art from 2020, even maybe my Painting Today book from 2009, but I couldn’t re-edit my Conceptual Art book from 1998. It belongs to a different time, a different world. And as for my first book which come out in 1986 it looks to me now as if it was written by another person, which in a way it was – a much younger me. How do you think about these tabletop paintings now? Are they something you could return to? Even paint some extra ones?

IW: You are right that time has passed. It’s a different context of desire and need. But with these table top paintings. it is about a subject matter that is timeless so, “Yes!” I could return to them. But for now, I am interested in the flatness of the space in them. So, I have actually started employing them again in my new work, to see how it belongs in the present tense.

TG: Thanks Ian, it has been great talking about these works and your studio practice. There is much we haven’t gotten to talk about: how you became an artist, your time in UK and Spain, and almost all of the work you made before the pandemic. Maybe we can cover that another time.

.