Nice Buenaventura in conversation with Tony Godfrey.

9th July & 13th August 2024

TG. We are sitting together in the gallery that represents you, Artinformal, and I was wondering, as I have never been there, what is your studio like? What sort of room do you work in?

NB. I work on the second floor of the three-storey house I share with my partner, Cos (Costantino Zicarelli), who, as you know, is also an artist. Maybe ninety percent of that floor is given over to our studio. We share that space. At the moment neither of us is using the space as we both have residencies elsewhere — myself at Casa Romana in Clark, Cos at La Trobe in Bendigo.

During more “normal” times I would take up the open space, meaning the landing. It’s not massive but it’s bigger than a typical landing. I have an unused door set on trestles as a table. The size is ideal for me. Cos tends to work in the enclosed area.

In the picture above you can see that behind my table is a wall entirely covered in plywood so that we can mock up stuff. Cos and I have a common affection for woodgrain, which probably makes my next solo exhibition after two years only natural: it’s called Mt. Pareidolia, opening 17th of September here at Artinformal.

TG. Is this what you are making in Clark?

NB. Partly, yes.

TG. What is it about?

NB. It’s about making meaning out of randomness, based on the term pareidolia itself: seeing meaningful images in random patterns, for example spotting faces in woodgrain.

TG. I recall Leonardo da Vinci told his students to look at the stains on the wall.

NB. Yes. Or children looking for bunnies in the clouds. I think that this direction started as a potential solution to the empath’s dilemma: I’ve become too concerned about too many things so that organising my ideas was just impossible. Often I felt I was responding to disparate concerns. This would eventually turn for the better when I came across archipelagic thinking. It made me realise that everything is actually connected.

TG. You have written an essay on archipelagic thinking.[1] Can you explain, briefly, what you mean by “archipelagic thinking”? Does it mean more than the interconnectedness between islands (or nations/cultures) as opposed to the insularity of the single island or nation/culture)?

NB. I mean “archipelagic thinking” as both metaphor and method. And so yes, I am referring to interconnectedness, but not restricted to geography or geology. In recent years, “thinking with the archipelago” has the impulse to react to one too many different things as part of the process. Now I even find satisfaction in discovering connections that one might describe as unlikely.

TG. You don’t have the luxury and continuity of always working with the same material – graphite, charcoal, paints, video, or code. Next year you could be working with totally different materials. In an interview we did five years ago you used the word “tension” as what drove your work.

NB. Yes, I did use that word, and still do to explain the work. Now that I think about it, unlikely connections make for tensions: two or more seemingly opposing ideas that form a fluid network underneath.

TG. A lot of your work has been done with what we could call mistakes, or natural variation. Right?

NB. Correct.

TG. I was very aware looking at your website the other day. It is quite curious: you have to move all the images out of the way to see the texts. I assume this deliberate.

NB. It is.

TG. It is sort of annoying, but it does make you participate – which I guess is what you wanted. And in listing old projects I was aware you are very reluctant to give dates. You want to keep things fluid, in flux, rather than tack them to a strict chronology.

NB. The annoying bit is not so deliberate—ha ha! I guess throughout the years what has been constant is that mistake-as-motif is my modus operandi. For example – this one [points at painting], which is one of many, is called Gaian Assembly. At first glance the impressions on the linen look random.

Nice Buenaventura. Gaian Assembly XIV, acrylic on dyed linen, 28 x 20 in, 2023, from the 2-person exhibition with Fyerool Darma (Singapore) and land erodes into at Calle Wright, curated by Carlos Quijon Jr.

TG. It looks as if it is derived from something typographic, or a photocopy of something typographic

NB. It is a kind of evolution from that. The reference material is printed matter. I chanced upon very badly photocopied texts from the American period[2], particularly of The Philippine Islands and Their People by the infamous D. C. Worcester. The copy I was able to download from the internet was very badly reproduced, and then digitised, so that the pages were filled with Xerox specks and scanner dust. For no particular reason I felt an urge to engage with that text, that copy. I didn’t know how to do so, until by chance I zoomed into one of the pages and realized that these specks, when magnified several thousand times, started to look like islands. And so, these shapes are not my design: they have real analogues in the world lifted from pages in that book. The artistic intervention is that I repeat some of these shapes, perhaps in keeping with the theme of reproduction.

TG. So you do fiddle with it.

NB. I do. There is some composition present. But most of the groupings—or Xerox archipelagos—are based on how the imperfection marks are grouped in the “original copy”.

TG. So you change some things it to make it look better? You are not a machine mechanically repeating things.

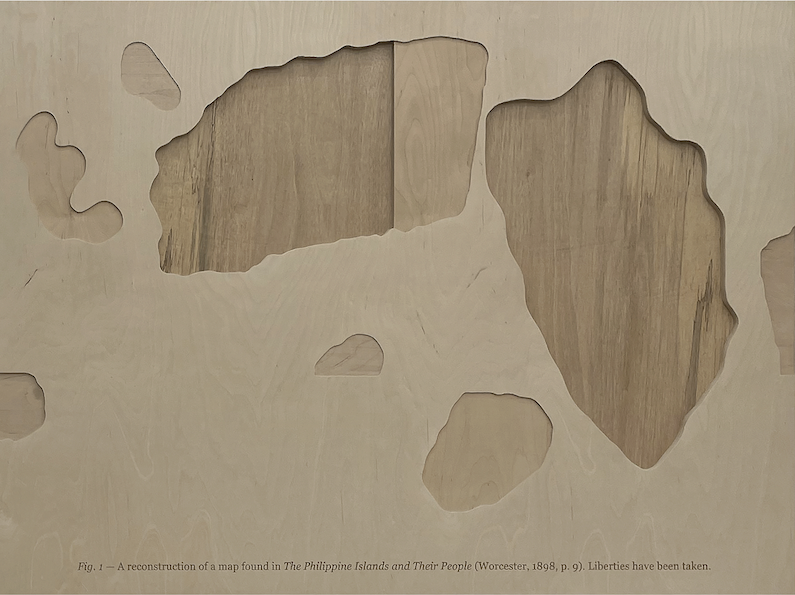

Nice Buenaventura. Gaian Assembly XV, laser engraved plywood, 48 x 34 in, 2023, from the 2-person exhibition with Fyerool Darma (Singapore) and land erodes into at Calle Wright, curated by Carlos Quijon Jr.

NB. Yes. I take liberties. I’m reminded of one of the pictures of Gaian Assembly that I sent you, the one made of plywood featuring a para-text at the bottom that is meant to look like a real caption. It says “fig. 1. – A reconstruction of a map found in The Philippine Islands and Their People (Worcester, 1898, p.9). Liberties have been taken.” So, yes, I do take liberties, pun intended.

TG. As often there is a political aspect to what you do. Here colonialism.

NB. Yes.

TG. I was also thinking of someone like Thomas Ruff who made enormous photographs based on star systems but would by selection, cropping etc. to aestheticise them – or even Vija Celmins who makes paintings of star photographs but by her slight adjustments make them more like art. They are amazingly beautiful in a way your average star chart isn’t. Do you similarly try and improve these aesthetically?

NB. Maybe subconsciously. I guess as an artist there is that tendency to produce something aesthetically pleasing. And so, despite the initial attraction to errors, and I do find them beautiful as they are, there is a knee-jerk reaction on my end to manipulate them a little bit and make them fit within certain parameters I have in mind.

TG. But you don’t set off thinking, “I will make this really beautiful”?

NB. No.

TG. I remember talking to the Singapore artist Guo-liang Tan who you will showing with in 2026 and whose works originate in quite a conceptual way but end up being beautiful in a sensuous way. He said that for him that any such beauty was an unintended by-product. Is that how you feel?

NB. You know, yeah! I have never thought of it in that way but now that you mention it, this is pretty true for me too. I was interviewed last month for the CCP Encyclopaedia of Visual Art, incidentally by a co-teacher at Ateneo. She was able to coax out of me something that I hadn’t articulated before: that maybe I am a researcher primarily, and I just happen to present my findings in an artistic way. Whenever I make art, it is almost always more of a by-product of a larger process.

TG. I think you belong to a particular kind of what I would call late conceptual art-makers that didn’t really exist until maybe thirty or forty years ago. But that is something I want to come back to. I am going to be boring and take you right back to the start. I know very little of your background, other than you did not go to art school.

NB. Yes, I didn’t—except later as a post-grad.

TG. What sort of family did you come from? Was it catholic by any chance?

NB. [laughter] Yes, of course.

TG. What a surprise!

NB. But my mum converted, became a born-again Christian. I never witnessed my father and mother argue until that time. They were like the ideal pair until they couldn’t agree on a faith to practice together anymore. That was the first—and maybe last—significant conflict between the two of them that I know of.

TG. So they go to different churches.

NB. It was a difficult time for us as my Mum would go off to a different church, and we would continue to go to the same one with our dad. These days neither of them goes to church, though I believe they still pray. They still believe the same things.

TG. Are you a believer?

NB. I believe in a higher order, if not power. I don’t go to church anymore.

TG. When did you last do confession?

NB. Oh, my! Maybe when I was still in high school! I went to a catholic high school.

TG. Would you define yourself, like most artists here, as a lapsed catholic?

NB. Possibly. It’s a grey area. Because I was brought up Catholic, when I am in trouble, I do subconsciously pray. I find myself praying. It’s not something I decide on doing. It’s an automatic response.

TG. But you don’t need to go to a church to do that.

NB. No.

TG. What sort of jobs did your mum and dad do?

NB. My mum was, and still is, an academic. She teaches mathematics. My father is an engineer by training. For a long time he ran an electronics manufacturing facility with some partners. I also worked there. I helped them out for maybe three years starting around 2012, sometime after I finished my degree in communication

TG. I don’t know how old you are.

NB. I turned forty this April.

TG. I thought you were younger. In your family’s house were there any art books?

NB. I can’t really recall. Three of my uncles though were very good painters, but they never pursued painting as a profession. I suppose you could say they were hobbyists. They also used to make these amazing sculptures out of cardboard that would end up as decorations in their homes. And my godfather, who was also my uncle on my Dad’s side, moonlighted as a portrait painter in his younger days. I really grew up with him; I was raised by aunts and uncles because my dad and mum had to work in the city. I grew up in Laguna. My mum and dad would leave me in the compound where my aunts and uncles had houses. When my godfather had commissions he would let me prime his canvases and watch him paint.

TG. Did that affect what you did later in life? Or suggest possibilities?

NB. A slow opening. Because, generally speaking, art in my family was seen as a hobby. All of my family ended up in business or some other corporate preoccupation. They did not see art as something you can make a living out of. It was discouraged. They would encourage you to draw—but only as a hobby. My first course at university was biochemistry, a pre-med course. Like typical Filipino parents of their generation, they encouraged me to become a doctor. I lasted a year at it and then transferred to communication in UP Manila. UP Manila, unlike UP Diliman, does not have a Fine Arts college. Much later I would take an MSc in media and arts technology at Queen Mary, University of London through a study grant.

TG. Or course I met you in London back in 2019. But you had been working as an artist long before that. When did you start making what we might call late conceptual art? And why?

NB. I think that from the beginning the work was always conceptual. I was a designer first, and was used to technology-aided work. When I decided to transition into art, tech was something that I carried with me, but more as a concept rather than a tool.

TG. So your BA in Communication was basically in Graphic Design, or what long ago was called Commercial Art. A degree that normally leads to a job in Advertising.

NB. Kind of. Immediately after finishing my undergrad. I worked primarily as a graphic designer, freelance or for an advertising firm. Most of the time I was working with and designing on computers.

TG. So from an early stage you had computer expertise.

NB. Just a bit more expert than your average computer user.

TG. Your education has not included such traditional things as life drawing.

NB. Only rarely, but you can see one of the works we will discuss includes a life drawing! A portrait of myself and my son. But it was based on a photograph that I photocopied, that I then copied as a painting.

Nice Buenaventura. Rewilding (Clap Game), charcoal and oil on canvas, based on a photograph by Czar Kristoff 22.5 x 15.25 in, 2020

TG. It is curious. In the UK I can think hardly of anyone who studied Graphic Design who then became an artist, but in the Philippines or Asia generally it is more common. Pow Martinez, Buen Calubayan and Jonathan Ching are examples. When did you first start to exhibit art?

NB. I think the first time I exhibited was at an art fair – on the recommendation of Dr. Rico Quimbo who had seen my drawings on Instagram. He told Soler Santos about me, and then Soler very generously asked me to participate in his West Gallery booth at Art Fair Philippines 2016.

TG. When you showed your drawings on Instagram, were you being a hobbyist or were you a potential professional artist trawling for contacts.

NB. [laughter] Yes, the latter! I had spent a considerable number of years doing advertising work, most of it corporate. I was done.

TG. So you had done ten years of graphics.

NB. I would say less because I worked with my dad for a while, and that had nothing to do with advertising.

TG. When was it you decided to try and be an artist?

NB. I think the desire was always there. It never faded away. As a child I wanted to paint like my uncle.

TG. If your parents had been more enthusiastic, would you have gone and doing a Fine Art degree?

NB. Yes.

TG. Has it been a problem for you not having done a Fine Art degree?

NB. Not really. In the beginning, occasionally I would think I was at a disadvantage, being older and without a BFA, but in hindsight my background has had a huge impact on how I work now. It was all part of the journey.

TG. I think “the journey” is a good way of putting it.

NB. I wouldn’t say I’m ecstatic whenever I tell anyone about what I did during my earlier years as a designer, but it is a past that I can acknowledge with ease today.

TG. What you make are drawings of things not made by people – accidental drawings.

Nice Buenaventura. Various works from her first solo exhibition Wave Drawing Nos. 11-12 at Artinformal in 2017

NB. I wouldn’t call this one (Wave Drawings) accidental. They are based on the vibrations of my drawing hand. This made up my first solo show ever, at Art Informal in Greenhills.[3] The tension then was all about labour, perhaps because I was making a transition between two different types of work: from design to art.

TG. You are defining yourself as an artist. One who is interested in the tension between the man-made and the machine-made, with a particular interest in wobbles or mistakes or natural variations.

NB. Yes, I would say that is very accurate. Looking back, it does seem like I was documenting that period of transition: from being used to creative executions on a computer to exploring creative executions with my hands.

TG. Tension and transition. This is something you said to me five years ago. If I remember right I asked, “Nice, do you start with materials?” and you replied, “No. I start with a tension. That is what I try to resolve through a process I’m comfortable with, like making. In some ways my practice is really just an offloading of personal and social tensions, but incidentally productive.[4]

There is, though it is maybe not obvious, an autobiographical element to your work. I don’t want to over exaggerate but there is an emotional investment there. Your work relates to your life.

NB. I think so too. For example, in Wave Drawings, you have a grid of gradients that are rendered in pencil by hand, and these are not random marks. They are based on the vibrations of my drawing hand as I was working, recorded using a kind of mobile seismograph that I had on my iPhone. It would output sine waves as it caught the vibrations on the table. I would then transcribe the waves into gradients—the bigger the wave, the darker the band.

TG. In a way it is recording energy.

NB. Yes. So whenever the gradient turns dark it shows you the times I was really going at it on the paper.

TG What are these five green blocks on the floor. How do they relate to the wave drawings?

NB. You prophesied my answer to this question! The floor work, titled Tools for Advanced Hospitality, in a way, is a representation of energy. They are resin-cast salt, copper carbonate that is green to be exact, in the shape of the negative spaces in the corners of my studio. It was meant to allude to the practice of sprinkling salt in the corners of a room to purify energy.

TG. At this point, 2017. You have come out fully as an artist. Are there other artists either around you or in the past who are helping you be who you are at that point. I don’t want to use the word “influence”, but artists that particularly interest you. That maybe confirm what you want to do.

NB. Cos is a large part, obviously. In terms of other artists whose work somewhat affirmed what I wanted to do… I think there were very few of them around during the time. Coming from a background in design, Minimalism was ingrained in me. I like sparse, gridded compositions. I felt that Minimalism was something only a handful of artists here were interested in.

TG. Minimalism never happened in South-east Asia.

NB. We have Maria Taniguchi, though I don’t know if she explicitly identifies with the movement. I knew her from when I was a designer. I didn’t even know she was an artist when I met her; it would’ve been cool. We also have Jon Cuyson who makes hard-edge paintings, among other things, and Celine Lee who makes very outwardly minimalist embroideries that are presented like paintings. Both of them I would meet much later.

TG. It is interesting you only refer to artists based in the Philippines. An artist that your work makes me think of is the Canadian artist Rodney Graham. But I can see from your face that name means nothing to you.

NB. Indeed.

TG. In the nineties we see a number of conceptual artists setting up a project by setting parameters and conditions to make manifest a concept. Rodney Graham is to me the epitome of this.[5] A late conceptual artist whose works were often very complicated. The American artist Stephen Prina who set up a project where he made exact size versions of all Manet’s painting – but as monochromes – is another. In one work Graham took the 9 extra bars that Wagner’s assistant Engelbert Humperdink (yes, he was really called that) composed that could be repeated and varied as fill in whilst complicated scenery was being changed during one of his operas. Graham had a computer work out all possible variants – that as a stand-alone piece of music could extend through several billion years!

Taking an idea and taking it to an extreme. I remember going to a lecture by him. It was a very dead-pan detailed presentation. The person I went with remarked afterwards, “he is such a Geek.”

NB. [laughter]

TG. Is there a geeky streak in your work too?

NB. Oh, definitely! I think the fact that a lot of my reference materials are text-based already leads one to presume.

TG. And there is the scientific feel of your works.

NB. As I have told people before, if I were better at maths, I would have become a scientist. Now, looking through this book of yours about Rodney Graham, I like how the images do not appear to be created by one person. I think that that is how my work tends to be.

TG. There is a different persona for each work. You do not have a signature style.

NB. Yes.

TG. But what is there are recurrent themes and interests. If you like, your signature style is in the nature of your inquiries. Dealers often find it hard to work with artists without a signature style. They can’t say to collectors, “this is an archetypal Nice” or “Nice is moving into a new phase: she is using larger brushes.”

NB. I think the collectors who collect my work tend to be – and I don’t want this to sound like a back-handed compliment – are the discerning kind. Those who are willing to spend more time than usual with the work in order to understand what the artist has to say. At the same time, I don’t believe that this is the only way to appreciate and to acquire art. To each their own.

TG. You are very fortunate that the young collectors here are prepared to be very experimental.

NB. I would agree.

TG. You do better here than you would in Singapore.

NB. Even I get surprised sometimes when my work sells.

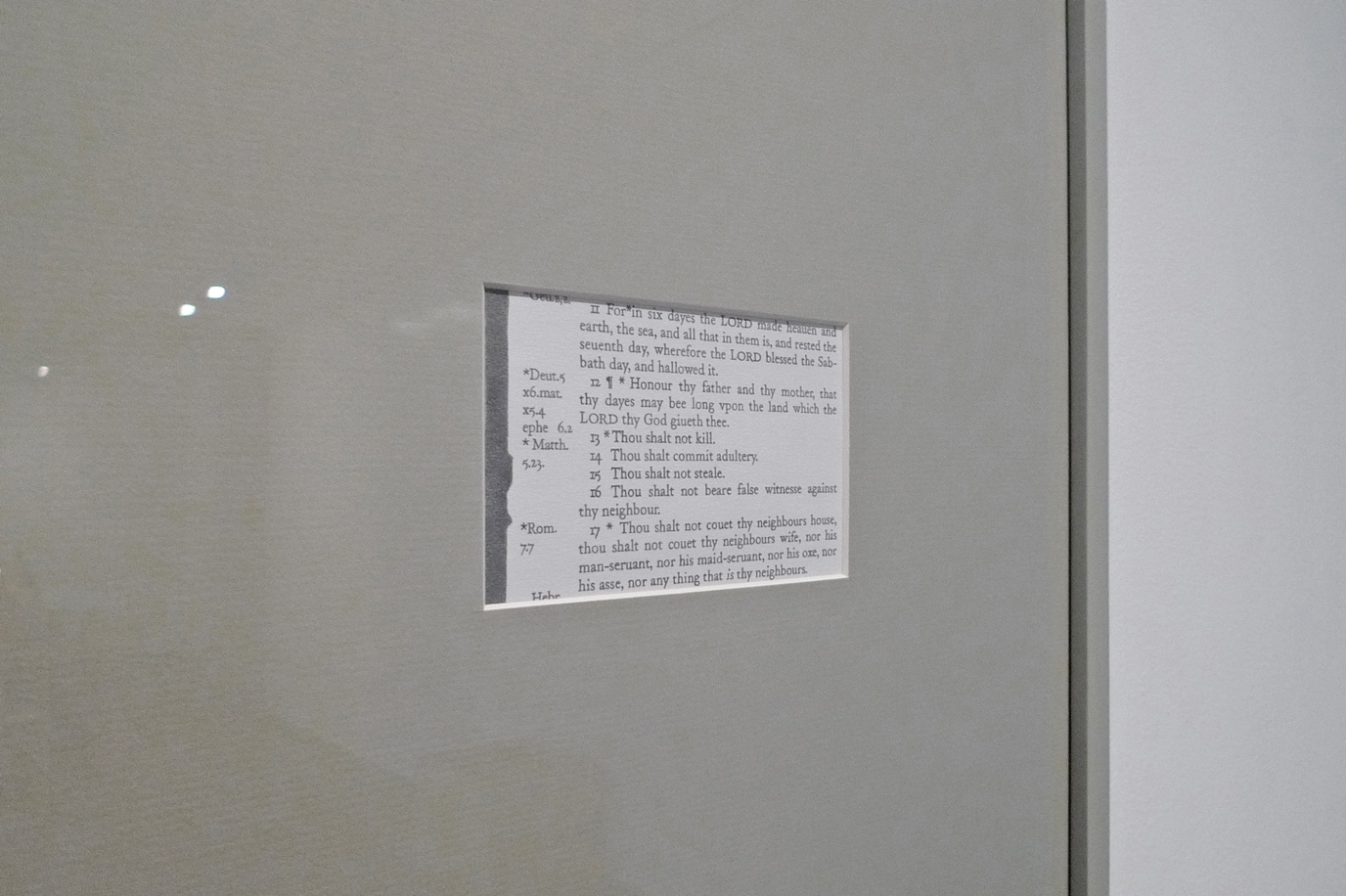

Nice Buenaventura. Wicked Bible. King James Version. London: Robert Barker and Martin Lucas, 1631, graphite on paper, 49.53 x 34.29 cm, 2019

TG. If I look at the work on the table in front of us, the Wicked Bible. Someone may ask, “why should I spend money for a degraded photocopy of a page from an old Bible – one where you are incorrectly told, ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’?”

NB. But this one is a drawing! Outwardly it doesn’t scream at you that it’s a drawing. You really have to look.

TG. A lot of your work is about asking the viewer to look harder. That is persistent in your work. I also think that is true of Cos’s work. I often don’t get it at first glance. Sometimes, unlike you, that is because he gives us a lot of stuff so it is difficult to process. You are much more minimalist than him.

NB. Yes, but I feel that he has become more open to the style, I guess because we work together and osmosis happens.

TG. So you are correcting him.

NB. [laughter] I think it goes both ways. He is also into print-based materials as references for his work. I am sure there is a lot of spontaneous seepage going on between our practices that it’s difficult to tell who influenced who. I think that it’s something we welcome. We have been noticing, actually, that we’ve started using the same things to conceptualise and make work.

TG. You did a collaborative exhibition with Cos at Art Informal last year.

NB. Yes, we both did paintings. My main contribution to that show was multiple paintings of the same portrait. It’s called Mateo, a Typical Philippino. It came from the same badly reproduced copy of the book that I got these specks from. [pointing at work on the table] The title of the show was As heavy as its weight in ghosts.

Various works (Left: Costantino Zicarelli, Right: Nice Buenaventura, a series of Mateo, A Typical Philippino, charcoal and oil on canvas, 12 x 9 in each) from the 2-person exhibition with Cos As heavy as its weight in ghosts at Artinformal in 2022

TG. How many images of Mateo did you do? I remember it was a lot.

NB. Twelve maybe. The first two Mateos were shown in CCP in 2022.

TG. When you were collaborating with Cos, was that an easy or difficult thing to do? Was it pre-planned or improvised?

NB. Improvised, mostly, but we had a vague idea of what we wanted to do individually. For example, I knew from the start I wanted to expand the Mateo series. In the end, it felt like two solo shows that just happened to bump into each other and then got along. There were no hiccups.

TG. On your website there is a project based on a map of all the islands running from Indonesia all the way down to New Zealand.

NB. Ah, the video work. Rocks scattered by the last breaths of the Pacific.

TG. One thing that interested me in coming to Singapore and Philippines was that people talk about the country as being in a block called South-east Asia. Or people here would talk about the colonial legacy from Spain and the USA. Sotheby’s sell old art from the Philippines as Latin American. That is where they place it culturally. But there is also a way in which you belong to Oceania – that vast island chain that runs from Sumatra to Easter Island or Stewart Island. Where do you place yourself?

NB. I have become more aware of the region in which I belong through some collaborations with NTU CCA Singapore. I’ve had the pleasure of working with the Magdalena Magiera, Angela Hoten and Uta Meta Bauer who were building a South-east Asian database of artistic practices that deal with ecology.

TG So it was when you were in Singapore that you started to think about archipelago?

NB. My awareness of South-east Asia as a region (and really only of Maritime South-east Asia[6]) just became more critical when I started working with people in or from Singapore. But the archipelago as a framework for thinking and doing—that started when the School of Commons at the Zurich University of the Arts commissioned an essay in 2020. Jasmine Wenzel, an acquaintance I met a while back, had a project under the school about island ecologies. She asked me to write a kind of experimental, free-form essay related to her research. When I was doing my own research on the subject I came across archipelagic thinking, and then I ended up with a visual essay contribution called The new word for world is archipelago, a title that is obviously a riff on The Word for World is Forest, a novella by Ursula Le Guin. In the essay I write about how the current climate crisis can be traced back to the Western colonial project, accompanied by documentations of a series called Thrashing Palm Tree—silhouettes of palm trees bending to strong forces during Tropical storms, made out of water on plywood. The water is held in place with a hydrophobic solution applied to the wood.

When you tap into that subject (colonial history) a lot of other issues crop up. I think that’s when I started feeling the weight of concern. There were so many things to react to all of a sudden. And so when I came across archipelagic thinking, not only through the usual suspects like Caribbean theorist Edouard Glissant, and—closer to home—through activist-author Bas Umali, but also through the many emerging academics who are invested in Island Studies, I found relief in the reality that many believe in the interconnectedness even of far-apart things. Colonial history and the current climate crisis, for example. These thoughts were stewing in my head in 2020 during the height of the pandemic; I had a lot of free time to read.

TG. Two questions. Firstly, you clearly express archipelagic thought in your writing, can you do so in your visual work?

NB. If I’m being honest, I would like to say yes. I mean, it is definitely an aspiration. I think that my exhibitions in the last few years, during and after the pandemic, have been broader in terms of conceptual scope. I like thinking of these exhibitions as written work that happen to be extruded into 3-D space. This also means, maybe, or I hope, that I now have a more acute sense of staging, of pacing, of confining works into “chapters” so that the art is legible to a certain degree.

TG. Secondly, did you enjoy the pandemic? So many artists I know answer, “yes I had so much uninterrupted time in the studio”.

NB. I feel guilty but I must admit I did. I am a recluse at heart. I have difficulty with sustained socialisations. A meeting like this doesn’t count. But teaching, for example, when I have to be in school for a fixed number of days a week, makes my anxiety a bit more difficult to manage.

TG. Teaching is stressful. I know. I did it most of my working life. It was how I made a living, where I spent most of my time and energy from 1984 to 2012.

NB. Full time.

TG. Most of that time. I was even in charge of a college for some years.

NB. I am so stressed even though I am only teaching part-time. But I guess part of the stress is that making art takes a lot of time and teaching takes a lot of that away.

TG. Teaching and making art is not an ideal combination.

NB. I used to think it was.

TG. So often I hear things like “I teach every Monday and Tuesday and on Wednesday I am burnt out”. It takes a while to get over the teaching. Your brain has been distracted and pulled in the wrong direction.

NB. There is also the shadow work of teaching.

TG. Especially nowadays – the ever-increasing amount of admin, necessary preparations, tutorial reports, and so on and so on. I first worked in an art college in 1978 and since then conditions have deteriorated so much. But let’s get back to your work. Specifically various Xerox portraits.

Nice Buenaventura. Various Xerox paintings. 2019.

NB. One of which is a portrait of me—but only as a shadow, with my son when he was a lot younger.

TG. What you have already said explains these. Paintings of photocopies.

NB. Paintings of errors I would say, not just photocopies, because some of them are based on printer errors rather than photocopier errors.

TG. It’s form of Photo-realism, isn’t it?

NB. Yeah, I would say so—of real printed matter.

TG. Is Photorealism a movement that ever interested you?

NB. No, not really. The closest to that would be the work on the left, which is from a page in an art book about a Roni Horn exhibition. A viewer walking past one of her floor-bound sculptures and in front of one of her drawings. You can tell from the way it is painted that the source image has been photocopied many times.

TG. It is a sort of photorealism which has none of the intentions of 1960’s Photorealism. The conceptual aspect of early photorealism, say Chuck Close at the start, got forgotten because it sold so well. American collectors saw it as a celebration of reality, not a critique of representation.

I can, btw, see why Roni Horn’s work would appeal to you. It is often based on errors or natural variation, but yet is very exact. And like you her work extends over many different media, especially text in her earlier work.

NB. The material for this show, which was called Fools will copy but copies will not fool, was a text by Walter Benjamin—The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

TG. I think I may have read that. I may even have given it out to students and made them read it. [laughter]

NB. I was required to read it for my post-grad. Having read it, and finding myself unsettled by the contradictions between Benjamin’s being a celebrated Marxist and his ideas about the aura, I felt an impulse to straighten things out for myself: by attempting to lend the aura of authenticity to the copy. I thought it was rather defeatist to say that the aura was the cultural authority, and that it can only belong to the original. And so in making paintings based on reproductions, even taking it a little further by choosing error-riddled reproductions, perhaps the aura can be possessed by the “lowly” copy too.

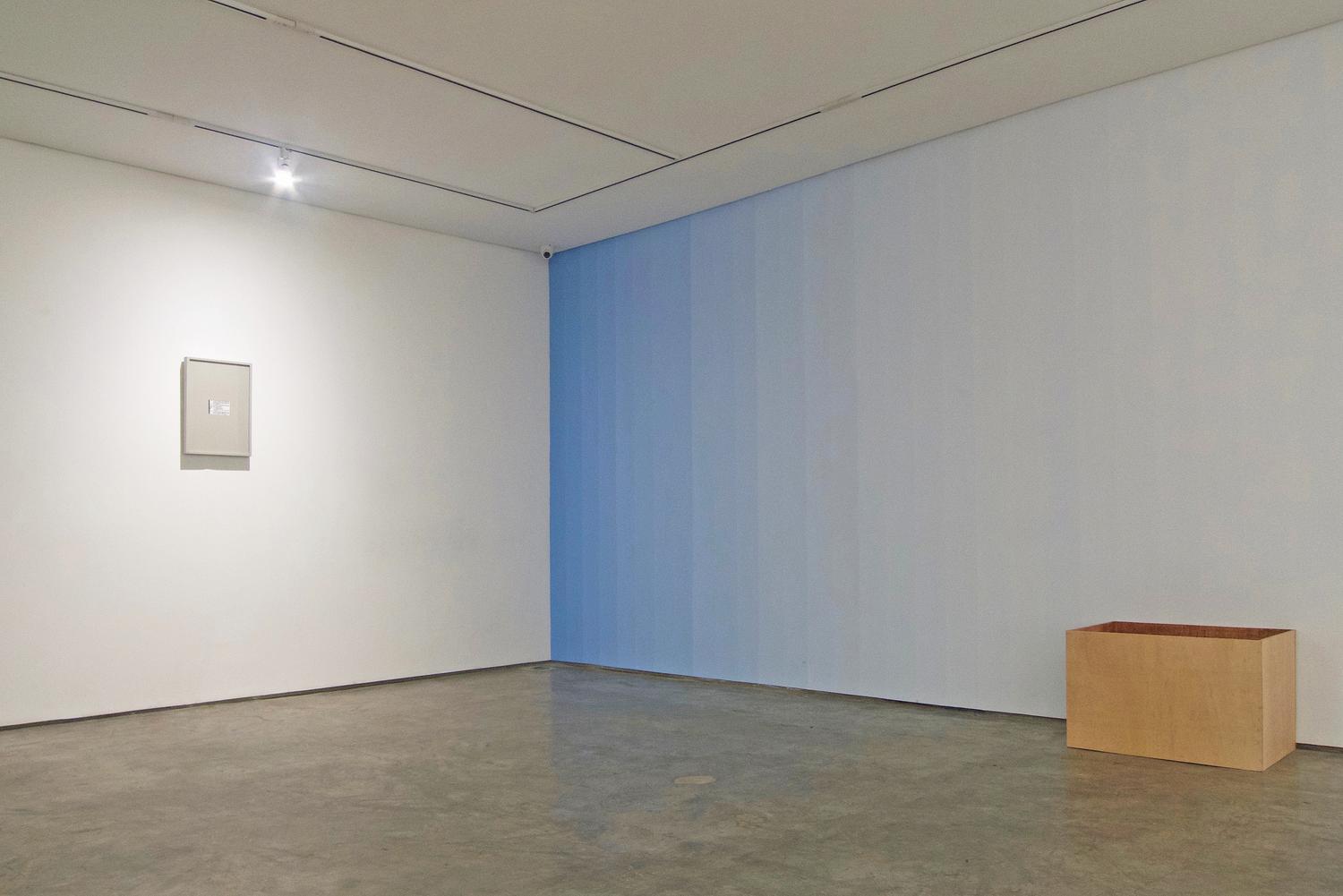

TG. What is the blue wall drawing on the right of the image?

NB. Printer manufacturers have websites, and these websites host forums where customers can ask for help in troubleshooting their printers. Most of the time they upload examples of erroneous print-outs. The blue wall is a copy of one such example from the Konica website. It is quite a goldmine of these abstract, geometric forms that happen to be errors.

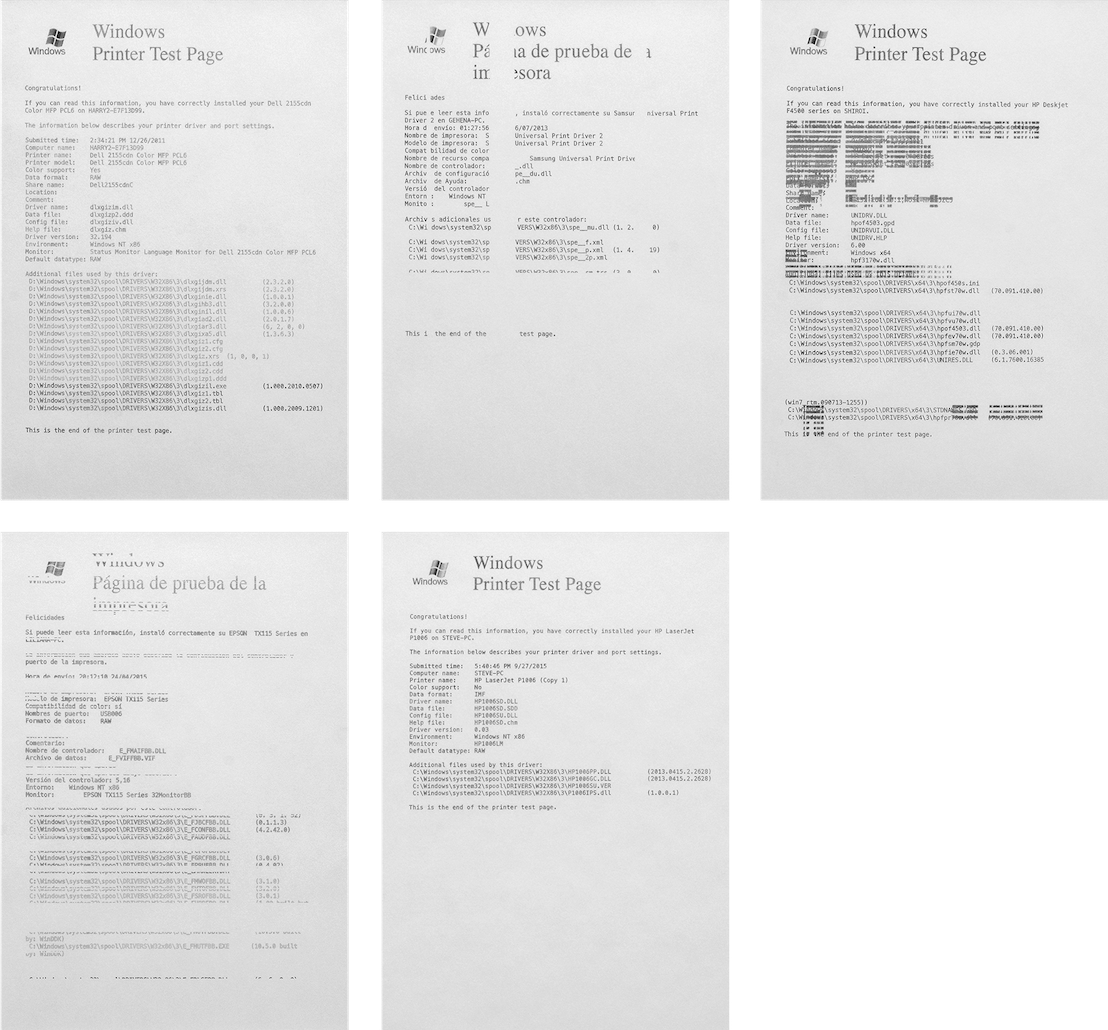

Nice Buenaventura. Pagina de Prueba de la Impresora, A4 each, 2018.

The earlier Pagina de Prueba de la Impresora series comes from the same thought process and also source material, except that it contains legible text and the final work is a drawing rather than a painting.

TG. Can you explain how you made Pagina de Prueba de la Impresora?

NB. When you buy a printer and you want to test if it is working, you print out something that is called a “Printer Test Page.” Pagina de la Prueba de la Impresora in Spanish. The series is a set of drawings of real test pages, erroneous ones, that were uploaded to the internet by users who needed help fixing their printers. I found ones with really interesting errors: inconsistent black tones, some streaks and ink smears, overlapping letters. I copied all these by hand using a pencil. When it was shown at West Gallery in 2018, unless you really paid attention, you probably would’ve said you saw some meaningless documents on the wall. When you give it a closer and longer look, the hand (and intent, I hope) reveals itself.

TG. How long did this take to do?

NB. A long time! That is why there were only a few works in the show. Wave Drawings also took a long time.

TG. This is like copying lines at school for punishment.

NB. Yes.

TG. Did it feel like a punishment?

NB. At times. I guess you could say it is like masochism. I feel delighted whenever I finish making these very difficult things, you know? Accomplishing something no one else can do.

TG. It does sound like a sort of religious exercise. Like Buddhists chanting or repeating the Heart Sutra. Do you work in silence or do you have the radio or music on as you work?

NB. It depends, but most of the time in silence. If there were one conflict in our shared studio, it’s this. Cos likes his music loud. I like music too but often not when I am working. Sometimes I play a movie instead. I don’t watch it, but I like hearing dialogue.

TG. There is something austere about your work. I guess that is an aspect of minimalism.

NB. It is austere in the final output. But if you consider the amount of labour that goes into the work maybe it is not so.

TG. I am reminded of reading that draftsmen who make Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings – ten thousand horizontal line, ten thousand diagonal lines and so on – can go into a trance-like state. Do you?

NB. Yes, I have been told or asked this a number of times. Meditative, they would say. I get that. I do lose track of time when I’m working on these labour-intensive pieces. Often I only stop when something starts to hurt.

TG. How long did it take to make this work?

NB. If I worked continuously everyday for, say, five hours, maybe a week for each page. But I can’t work like that; I need breaks because of the strain on my back and my wrists and my eyes. While in London I found this super cool contraption designed for manicurists on Amazon. It’s a lamp with a bendy stand and a magnifying lens. I can’t draw this without it now.

Nice Buenaventura. Fools will copy but copies will not fool (Partial installation view). 2019.

TG. In the image above what is the relationship between the text work on the left (the Wicked bible) and the wall drawing on the right.

NB. They are both print rejects. The first one rejected by members of the faith, the second by someone having trouble with their cyan ink cartridge.

TG. Did you paint it yourself?

NB. No. Romano, who works here, did. I gave him some instructions, and he was able to execute it the way I imagined it. The box to the side of this wall contained actual print-outs of printing errors I composited that people were free to take home.

Nice Buenaventura. Boolean Garden (Dormilones). 2019

TG. What is a Boolean Garden?

NB. I made this in London, with all the assistance I could get from the teaching assistant in a class called Interactive Digital Multimedia Techniques. I have been meaning to revisit this but it can be quite costly: it involves electronics and programming that I cannot do alone.

TG. You need a geek.

NB. Yes, a bigger geek than I! Anyway, Boolean Garden is a project that I can best describe as techno-botanical: it attempts to make a connection between nature and technology.

TG. If you put your hand close by does the plant jump around?

NB. Yes, and it produces a sound.

TG. What sort of sound?

NB. In the beginning it was a jarring noise, to keep you away, as a makahiya does, but my professor said the installation should encourage interactivity. Haha! So I changed the sound to something a bit more melodious. I’m very proud of the coded gradient here: the closer you get, the more vigorous the shaking and the louder the sound.

13th August

Nice Buenaventura. Thrashing Palm Trees with installation view. 2020-2022.

TG. I am looking at an image of your work Thrashing Palm Trees. And I have to ask a very obvious question: “What is this made of? Is it a painting?” It looks literally like water spilt on wood.

NB. It is exactly that.

TG. How did you stop it drying out?

NB. I wasn’t able to.

TG It must have been a very short-lived work!

NB. I think we could call it a durational installation.

TG. A matter of minutes or hours?

NB. Hours. We did a bunch of testing.

TG. What was your reason for making something that was so temporary?

NB. That it would be temporary was an afterthought. It was more that I wanted to use water as a medium. I created this after suffering indoor flooding in the middle of the pandemic. Do you remember Typhoon Rolly? That was a very bad time for us at home.

TG. You said you wanted to work with water. In a way the medium – in this case water – often leads you to wherever it is you are going.

NB. Yeah, it’s the second factor that defines the final outcome, next to tension. I have conflicting feelings about water: that fascination and fear that are at odds with one another. I felt that tension needed to be resolved somehow.

TG. Why do you fear water. Are you a good swimmer?

NB. The fear comes more from my anxiety of things getting drenched in dirty sewage water. I do know how to swim; this is more about flooding.

TG. This is a massive issue in Manila. When Geraldine lived in Sampaloc a flood got into Geraldine’s store room and destroyed all her early catalogues.

NB. Flooding is a massive issue, especially in our area—the Scout area in Quezon City. Unfortunately, our house sits on the lowest point of the street. Whenever there is a storm, water and debris rush into the front of our house.

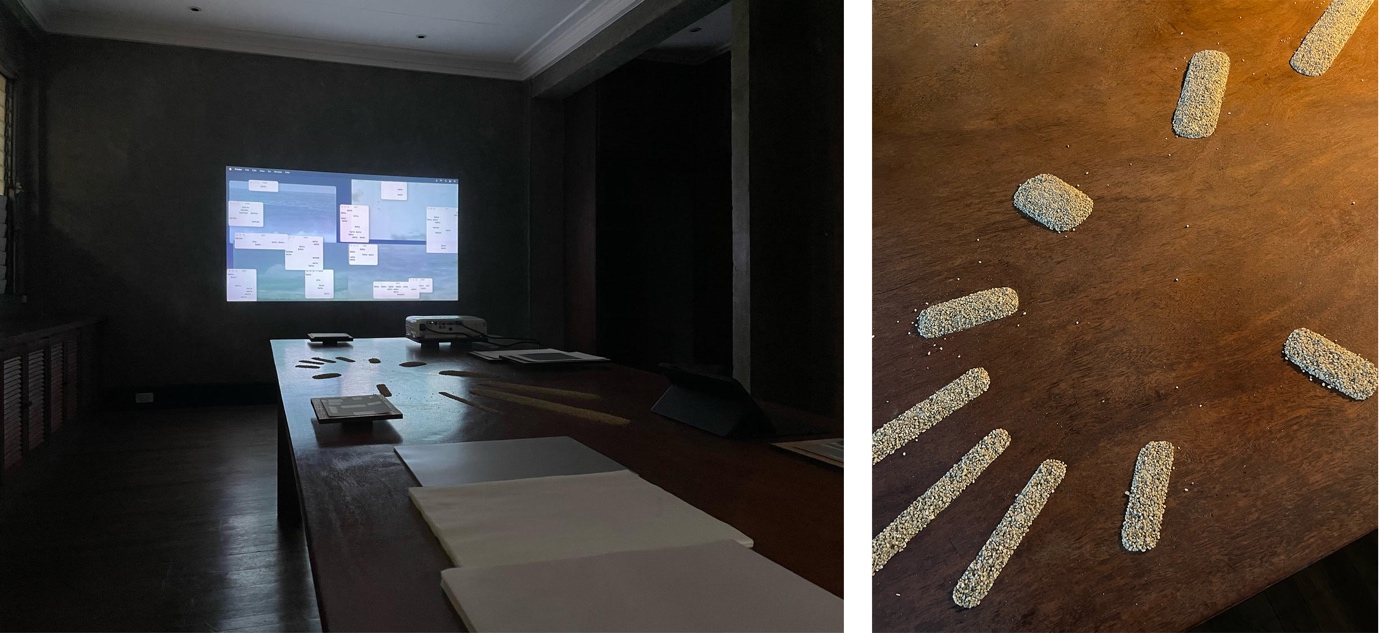

Nice Buenaventura. Rocks scattered by the last breaths of the Pacific (Installation view) & Buffering Sun (Detail view). 2023

TG. And now I am looking at an image of Rocks scattered by the last breaths of the Pacific and Buffering Sun from 2023.

NB. Oh… the video!

TG. You describe it as a video, not as an installation.

NB. Well, yes, because having the table there was an idea that came after and was actually suggested by the curator [Carlos Quijon Jr.]. Originally, what I had envisaged was just the video and the accompanying text.

TG. Would you have preferred to have left it that way?

NB. Actually, no. I think in the end I preferred that it was an installation because the things on the table all had something to say about the video. I think this made the ideas behind Rocks… easier to appreciate.

TG. It allowed more participation from the visitors: they could pick those things up.

NB. Pick up in the sense that they can read more about the video work. The participation bit also applies to the way the piece was produced: the montage is composed of citizen-footage of storms occurring over the Pacific. I asked YouTube content creators for permission to use clips of their videos. So, in a sense, the work features the participation of strangers on the internet.

TG. Talking about collaborations. This was also a collaboration between you and a curator. Do you work that way often?

NB. No, not at all. It was the first time I had worked closely with a curator. Usually, curators I have worked with in the past would give us artists free rein, just a very loose prompt. With Carlos it was very different: he was involved in every step of the process, though, of course, while allowing us artists some freedom to assert artistic input. There were only two artists in this show, a small team. Because of this it was easy to find a compromise amongst three creative minds.

Tony, how do you work as a curator?

TG. A few years ago I was at a conference on curating with Patrick Flores and others. “My main job for many years,” I said, “was teaching and that affects how I curate. For me an exhibition is like a seminar: I set the theme or give out a reading. Some people just do whatever they normally do, others react to the theme and some engage in a conversation with me.” I am fairly hands off. I don’t have any anxiety about not being in a commanding position. I work with artists because I am interested in them, maybe I can help translate things. There have been exhibitions where I have done little more than say “would you like another cup of coffee” and exhibitions where there are long discussions and I might suggest alternative ways of doing things. Above all I am a writer: my main contribution is often an essay or an interview.

NB. So there are different curating styles?

TG. Yes, personality is involved and so, sometimes is ambition. The final work we planned to talk about was Gaian Assembly. Am I right I thinking this is a group of many works?

Nice Buenaventura. Gaian Assembly XVII, graphite and water-based binders on canvas, 4×3 ft, 2024

NB. Yes, it’s ongoing and actually evolving for this upcoming exhibition. Since 2022 when I made the first Gaian Assembly painting, I have been obsessed with xerox and scanner dust. I have developed a fascination for finding badly-reproduced archival texts. Cos shares this fascination: we have found a gold mine of material that suits our preference for photocopies. By virtue of them being photocopied you can readily say they have been badly reproduced. Digitising these for consumption on a screen adds another layer of bad reproduction: on top of xerox dust you have scanner dust. Accidentally

I zoomed into these specks and started seeing meaningful things in all that randomness: the specks started to appear like islands. So, the inside joke about Gaian Assembly is they’re made of xerox islands.

TG. Xerox Islands would have been a great title too. “Gaian” is presumably a reference to James Lovelock and his concept of the earth as a living entity.

NB. Yes, and to the general idea of the earth acting as one organism. Gaian Assembly is a phrase I made up for the essay I mentioned earlier. When this work came to be it just felt connected to those words – groupings of islands, seemingly discrete but actually interconnected underneath.

TG. Nice in the process of doing this interview we have talked about many things. Is there something else you want to say? Some question I should have asked?

NB. That just goes to show how I am responding to too many things. Thanks to “thinking with archipelago”, I don’t feel terrible about being a sponge and having to deal with varied issues because, underneath, everything is connected.

TG. All the dust will settle down in the one place eventually.

NB. Thank you for putting it so poetically. [laughter]

-

See “The New Word for World is Archipelago” at https://nicebuenaventura.com ↑

-

From 1899 to 1946 when the Philippines were a colony of the USA. ↑

-

Art Informal was originally based in Greenhills, an area of Manila then they opened a second branch Karivin Alley, Makati close to other galleries. Last year the branch in Greenhills was closed. ↑

-

Published by Art Informal in 2020 as part of a catalogue for ALT art fair. [?] Should we add the whole interview as an appendix? ↑

-

Rodney Graham. Vexation Island is it on you-tube? ↑

-

Basically the island based countries: Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore & The Philippines. Northern South-east Asia being part of the Asian land mass and having a strong Buddhist culture is different, ↑