BUEN CALUBAYAN IN CONVERSATION WITH TONY GODFREY

December 2023 – August 2024

Part One, by email, 16th December 2023 onwards

TG. Hi Buen. It was good to meet yesterday. You mentioned you left Manila during the pandemic and lived in the country in Pampanga – and that you got a dog. What sort? Has having a dog changed the way you see the world? and changed how you make art? Tony

BC. Hi Tony. It was good to meet you too. Yes, we got Nissin, she is an American bully. She has been a source of joy and distraction which is changing our daily routine, my mornings, and yes, the way I do my work and art, in many ways.

TG. Can you be more specific “in what many ways”?

BC. Well, in our morning walks, for instance, she brings me to some places in the village where I get to observe the surroundings. This is where I look for diagrams at work: “sniffing” into nature; in the atmosphere; in our movements and navigation, smell and sound. I use this as a focusing tool and grounding for the day ahead.

TG. Walking with my dog, Ragnar, a Golden Retriever, I am likewise made very aware of his utterly different perception of the world, one based primarily on smell not sight. At what point did our human ancestors start to prioritise sight over smell. Maybe when they learnt to walk on two legs?

BC. They (dogs) have a different conception of the world, for sure, but one that we may never access. Indeed, we still have to develop or rediscover our sensory capacities to bring about the possibility of another world. We have been relying on our sense of sight for too long in order to survive, now we have reduced the world to fit the size of pixels and retinas. My work addressed this.

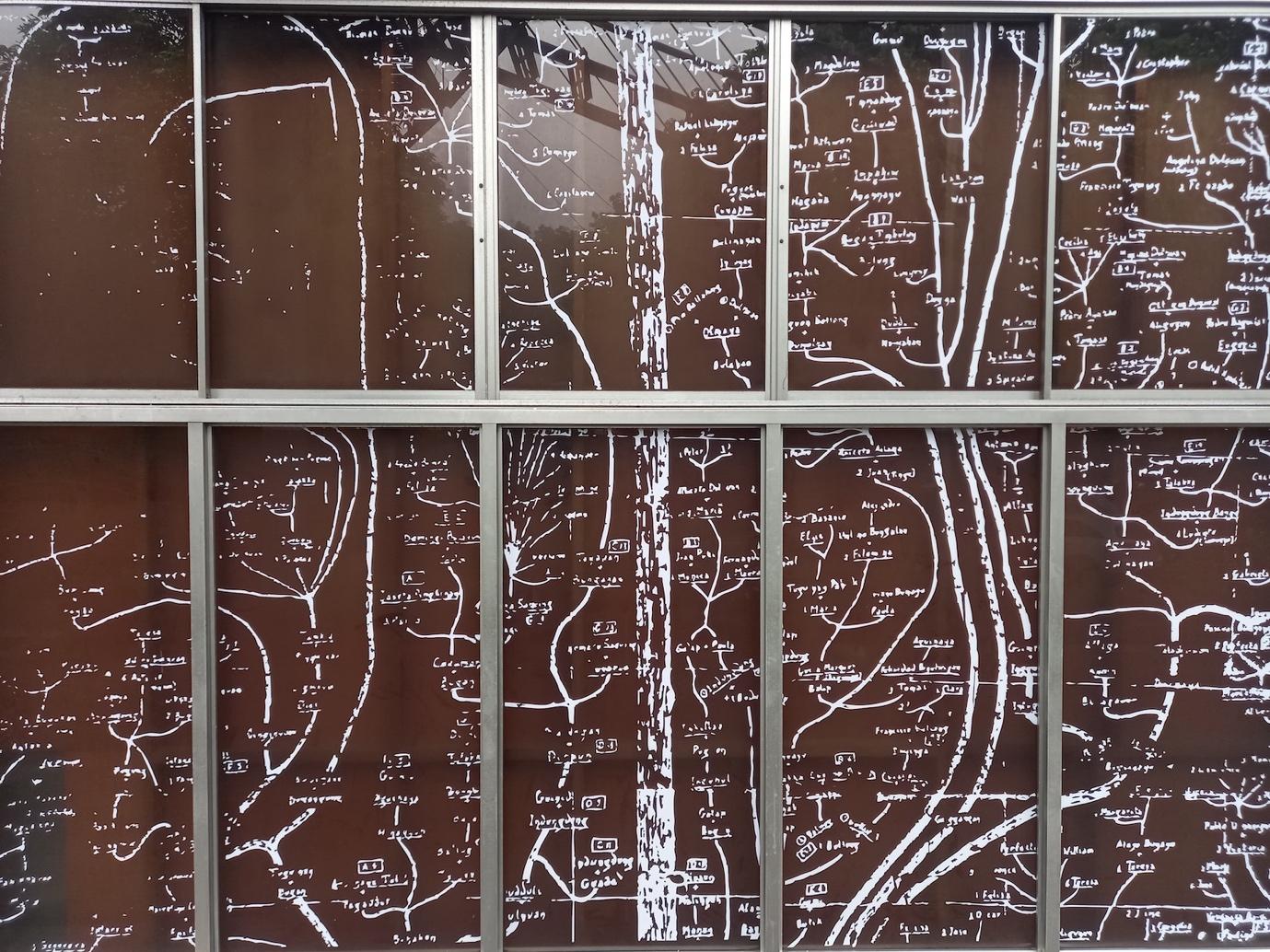

TG. As always with these interviews I have asked you to choose eight works from your career, early and late. But I am very aware that some of your works are extremely discursive. As I understand it your current ongoing exhibition at Vargas Museum is a sort of critical gesamtekunstwerk involving large diagrams placed on all the ground floor windows, a video projection, tables covered with notes, sketchbooks and books, and four workshops. We need more than one image to illustrate what you are trying to do!

As I understand it, the diagrams are the key. Is that correct?

BC. As you rightly mentioned, the diagrams are the key. It keeps the research project intact: from sensing, to what is being sensed, and the tools in-between. Maybe we can start with the work “Instructions on viewing the landscape”, the diagram of linear perspective itself from which we are using as a tool of picturing and as a framework of world-making.

Buen Calubayan, Instructions on viewing the landscape, 2023

Buen Calubayan, Instructions on viewing the landscape, 2023

TG. A couple of quick questions first. Are the diagrams all taken from other sources? To what extent, other than enlarging them, do you adapt them or invent?

BC. Most of the diagrams are assembled or modified from existing ones and archival materials. Some I make from scratch. And some are drawn during lectures and study sessions. They have been previously published and exhibited. This time, with new diagrams, I am looking for ways of activation that attempt to dismantle one point-perspective and make the viewer move through workshops, pedagogy, rhythm-analysis, among others.

TG. So your diagrams can be seen as being simultaneously art works and didactic tools. I am interested in your use of the words “activation” and “dismantle”. Can these diagrams be seen as models of a false consciousness which analysis can puncture or re-evaluate? This sounds, I know, rather Marxist. The goal for Marx, and later Gramsci, was not just to challenge false consciousness or ideology but to pave the way for the dictatorship of the proletariat and beyond that a world of harmony where we are no longer estranged (a more accurate translation of the word Marx uses “entfremdung” than “alienation”) from both our work and society but also from our environment. Is your goal similar? How can you assess the effectivity of your project?

Also, BTW, what is “rhythm-analysis”

BC. Yes. Diagrams are inherently didactic tools. But they are not meant to be looked at, like a static work of art. Their effectivity lies in their capacity to align people to the movements of their bodies and their surroundings, merging through purposeful work and the rhythms of everyday life (rhythm-analysis)—paving the way for (I suppose a “better”) world/event to come. In this way, it projects a similar (Marxist if you may) goal from which activation and dismantling threads through the same horizon line towards reaching or abolishing a supposed “vanishing point”.

With regards to its assessment, it is easier to see the results from the workshops and learning sessions, or from its future influence on curriculums and policies. But from a wider and deeper sense, like most works of art, it will need time and may be difficult to assess.

TG. I find myself thinking about a lot about some of the arguments I was involved with in the 1980s with artists such as Victor Burgin where ideas from Marxist theory (including Althusser) psychoanalysis (including Lacan) semiotics and feminism were conjoined, and in which single point perspective was seen as being deeply connected with a domineering male and colonizing gaze. Is there a feminist and post-colonial aspect to your project?

BC. I just came across Victor Burgin from Aesthetics Equals Politics by Mark Foster Gage.[1] That is the direction I am working on: towards the counter-aesthetic strategies where the pedagogical aspects of housework in relation to rhythms of everyday life; forms of affect; indigenous knowledge systems; among others are being examined. If you look at the diagrams related to Kiangan and Banahaw, they have multi-point, multi-sensorial dimensions that are not aligned with the single point perspective which tends to flatten worlds and experiences. You don’t gaze at the diagrams, you should become the diagram.

Buen Calubayan, Banahaw diagrams, 2023

Buen Calubayan, Banahaw diagrams, 2023

Buen Calubayan, Digitally modified Genealogical chart of Kiangan, 2023

Buen Calubayan, Digitally modified Genealogical chart of Kiangan, 2023

TG. Let’s come back to that later. As I understand it the seminars you run during the exhibition are an integral part of the project. What exactly do you examine and do in these seminars?

BC. The workshops are designed to address three things: First is the experience of the landscape and the activation of the diagrams pertaining to the Steiner-Waldorf pedagogy through lazure painting and form drawing workshops. These workshops reorient the self and the collective through movements, rhythm, and sensing as the images and forms unfold with the body and space. (The Lazure painting workshop was facilitated by Lormie Lazo, Maria Ester Samaniego, and Kara Escay. The Form drawing workshop was facilitated by Lormie Lazo.) Second is sensing the world through the Sense capacity building workshop which combines strategies of team building activity in a corporate setting; circle time in a Waldorf classroom; and improvisations in theatre and performance arts. The workshop is intended to activate the merging of the body, the environment it occupies, and the tools at work in between, at their full capacities. (This was facilitated by Deo Briones and Thea Marabut) Lastly, there was the Situated reading session, which hoped to open a dialogue on forms of resistance and collective de-centring of the West. The session is intended to unpack perspectives on land and indigeneity using intersectional, political, and global lenses. (This was facilitated by Con Cabrera)

TG. Buen, this is such a complex project that we could discuss it for the rest of the day, but I want to pause here. As always in these interviews I want to go back to how your career started, work through some sample works and then perhaps return to this Vargas project and other new related projects.

What sort of social, family background do you come from? Were your parents interested in art? When and why did you start to get interested in art?

BC. Hmm. I am a product of middle-class catholic upbringing. Trad. educ. The golden child syndrome. The one who is rewarded for doing good deeds, obeying authority, winning awards, and speaking in English. Consumerism is key. My parents were not in the arts but they are artistic. They supported my choice to study fine arts. I can recall having a childhood well-spent in playing and drawing. The walls in our house are full of my markings, but not without occasional punishments, of course. I would always draw in my notebooks. When I was seventeen I was very sure I would take the art-track. I think my interest in art comes from a deeper interest in formulating questions of philosophy and aesthetics.

TG. When do you think this questioning attitude and this interest in philosophy began?

BC. When I was in college and suddenly, I realized I should have taken painting as a major instead of advertising. Then a questioning of my religion, upbringing, and authority in general followed. I remember reading a lot of atheist, existentialist, and anarchist materials at that time.

TG. To clarify. You went to UST (University of Santo Tomas – the oldest university in Asia) at what age? You focused on Fine Arts – Advertising not Fine Arts – Painting. Why? How old were you when you realized you should be in Painting major. Did you transfer to Painting?

BC. I was seventeen. I took fine arts major in advertising at UST. In my third year, aged nineteen, my plates would look like the works of painting students. But I never transferred. So I finished fine arts with a major in advertising in 2001.

Part two, at Buen’s house and studio in Quezon City, Metro Manila,

17th July 2024

TG. We got stuck eight months ago talking about your time at UST. You took a major in advertising there not painting.

BC. Yes, I graduated in Advertising.

TG. How has that affected you? Has it been a problem doing that rather than painting?

BC. I see it as an advantage. Number one: I learned to avoid advertising! But it gave me some tools that I use in my current work. Painting I learned from my friends and by doing it.

TG. Technical or intellectual tools?

BC. Both. I can lay out my catalogue. I can do graphic stuff. Poster design. I use these tools in making diagrams.

TG. We shall come back to: the relationship in your work between paintings and diagrams. To fill in people outside The Philippines, UST – the University of Santo Tomas – is the oldest university in Asia. Set up by the Dominicans it remains staunchly catholic. This makes it different to UP (University of the Philippines) set up by the state and which most artists I meet come from; in particular from UP, Diliman – the branch in Quezon City in the North of Manila.

Did you have contact in the Fine Art department when you were at UST?

BC. In the Advertising route we did several Fine Art modules: drawing from life, outdoor free-hand drawing, but we did other things such as marketing.

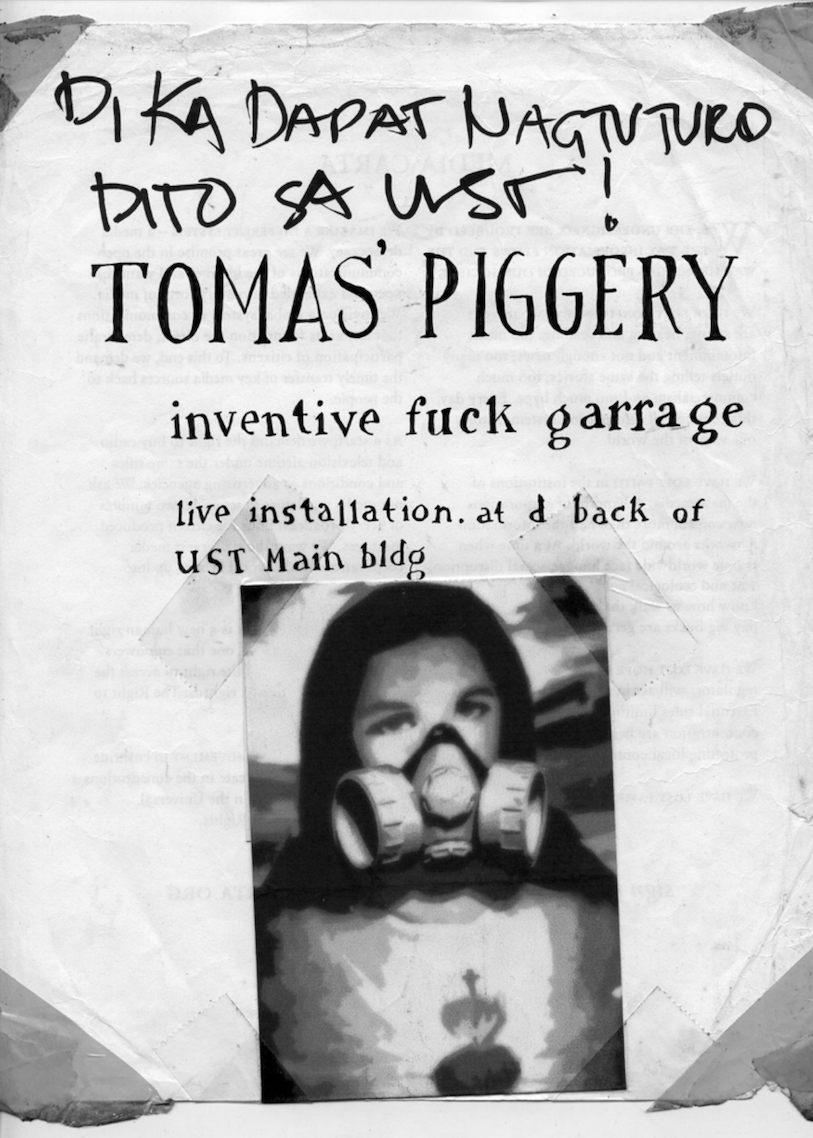

TG. You had a censorship problem at UST. Can you tell me what happened?

BC. This happened after I had graduated, when I taught at the College of Fine Arts and Design in UST while also working at the UST museum. I did a project. There was a construction site at UST. I declared it as an installation site, that it was an in situ art work. Then I made a poster about it. This poster has an image of Jesus Christ with a gas mask on. It was a typical protest work where you channel out some of your frustrations with society, and the corrupt system. Basically, Jesus Christ has to wear a gas mask as protection against all this.

TG. But a priest objected.

BC. He said the opposite: that I making out Jesus Christ was a terrorist. Yet, actually, that poster created no scandal when I made it. After a year there was a change of management and there was a new priest. Every college at UST has a designated priest. The previous priest had not been bothered by seeing my poster or maybe he didn’t see it. But this new priest wanted to make changes around the college such as a strictly imposed dress code. We questioned that because when you paint you should wear working clothes. That became an issue. I suspect that A professor who had taken a photo of my poster a year before gave it to this new priest. I was terminated without due process. I had no teaching for the next school year.

All I got was a letter saying my contract was terminated, no evidence attached to support the reason given. It was only later during the proceedings at the labour court that I found out I had been accused of blasphemy – “defiance and open display of atheistic ideas.”

I had gone to the union of the faculty and they helped me file a case because the management had not followed due processes and we went to National Labour Relations Commission (the Labour Court). This all took three years and the final decision was that UST would have to pay a penalty because of the lack of due process but the grievance – open display of atheistic ideas – was valid. So I lost the case.

TG. What have you been teaching?

BC. Foundation courses: free hand drawing, drawing from life. I had been teaching for five years before all this happened. The case took a long time. I just had to look for other jobs. I published the decision of the court – in the style of a prayer booklet. And the cover was the image of Jesus with his gas mask.

Buen Calubayan, Decision (cover of booklet), 2010

Buen Calubayan, Decision (cover of booklet), 2010

TG. This all sound so bizarre to someone like me who went to a university in the UK. There is a dress code! Atheism not permitted! Staff being sacked for no given reason!

BC. Of course the uniform is a way of controlling people – part of catholic obedience. [laughs]

TG. Is this what changed your direction from Fine Arts – Advertising to Fine Arts – Painting?

BC. I think I have changed already. By my third year in Advertising, I had realized I wanted to paint. But I never shifted because [pause] I am also somehow still obedient to my parents. There were financial reasons too: I did not want to burden my parents with another year in school. I was able to side-track things: even though I was in Advertising my projects would look like the plates[2] of a painting student. And I really didn’t care about the grades. It was something else I wanted to pursue. Even back in High School I think I was certain I wanted to be an artist.

TG. Was it your parents who wanted you to do Advertising?

BC. No, actually, in my province, in Lucena, I was not well informed when I was choosing my course. A cousin of mine was studying Fine Arts Advertising in UST. And I thought that’s the course I want to do because I can make artworks. I didn’t understand that there are different majors in a Fine Arts School.

TG. There was little knowledge of art in your home?

BC. My parents for example knew nothing of Makiling – the high school for the arts in Los Baños. One of my batchmates went there. But in retrospect I am glad I didn’t go there: it was better for me to have a wider perspective in my teenage years, not to be specialised at an early age.

TG. You are one of the few artists I knew who has a room especially designated as “The Library”. Writing and theory are important to you now. When did you first start to get interested in theoretical issues?

BC. I realise it started when I began to question my upbringing – especially strict Catholicism. Later I realised it is a type of trauma. You are moulded into a certain type of person and suddenly you are open to the world and it is different from what you have been told. It is a philosophical, existential question. Primarily I questioned my religion. During college and right after college I began reading a lot of atheist books and anarchist books. It opened my mind.

TG. You stopped going to church? When did you last go?

BC. When I need to accompany my friends or relatives there, I am OK with that. But it was a very long time ago that I went on my own. After college I did a lot of blasphemous works in order to exorcise my Catholicism and project some visual trauma to the believers. Maybe it’s my personal way of processing things.

TG. Did you exhibit these works?

BC. Yes. Images of Jesus Christ, Mother Mary. You name it I bastardised that image with scars, whatever. I realised later on that you believe in something for a very long time and then you question it. Art became a medium to question it, to face the self that had been moulded since childhood and which you don’t want anymore.

TG. You questioned all the assumptions you were brought up with?

BC. Yes. And I have every right to because it’s like a scar in your body, in yourself. But it will never be erased.

TG. You will always be a Catholic, even if you are a lapsed Catholic.

BC. Yes, I will always be obedient and compliant. I also learned that you don’t have to erase it. You just have to put a room in your self for it. It’s there. You have to deal with it. You have to live with it. Or live above it.

TG. I think it is the same for me. You know my father was a priest. Anglican, not Catholic, of course. I went to church every Sunday but it wasn’t as oppressive or as intrusive as the Catholic Church. I don’t have the faith my father had, but I never felt the need to rebel as you. I am comfortable with it. It is part of me. It matters.

BC. It matters. It affects you through your parent’s attitudes as well.

TG. My parents lived the Second World War. Like all their generation they were very patriotic and very obedient. In those days – late Fifties, early Sixties – at the end of the evening’s TV they would play the National Anthem. My father would always stand up for it. The other side to this obedience or deference was a very strong sense of community – a shared purpose.

BC. A sense of community, a shared purpose and also rituals. It helps you with the everyday rhythm of life. Praying for example. All this doesn’t go away. It just changes. You adapt.

TG. The ideology lingers.

BC. At the time I made those blasphemous works I was like a soldier trying to agitate people. But maybe I made them do the things I was rebelling about! I pushed them back into their prejudices. So, I realised this was not working. It doesn’t take you anywhere.

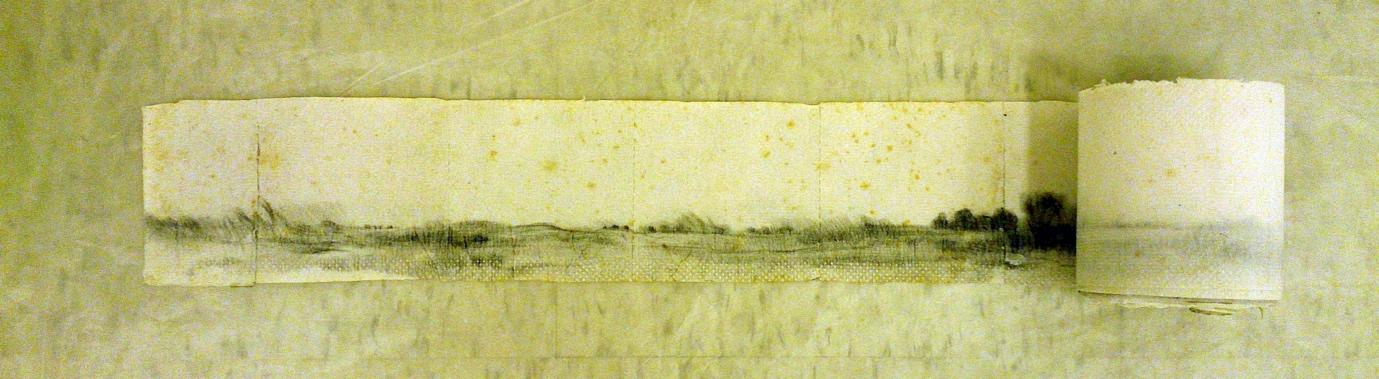

TG. At what point did you start to become interested in landscape? The first work you have chosen to talk about Eternal Landscape Painted on toilet paper, dated 2010 to 2013. Is that how long it took to make?

Buen Calubayan, Eternal Landscape, 2010-13, 463 inches long

Buen Calubayan, Eternal Landscape, 2010-13, 463 inches long

BC. I started it and then kept coming back to it. The reference for that landscape is the Hacienda Luisita and the massacre there. The contested farm land of the Aquino family. [The Aquino family clung on to this 6453 hectare sugar plantation despite the 1988 supposed land reform. In 2004 striking workers were attacked by police and soldiers attacked killing seven and injuring many. Peasant leaders were subsequently found murdered. In 2018 4099 hectares was transferred to farmers.TG]

TG. So even landscape is political to you. This is landscape art as agitprop.

BC. The work was never meant to be preserved. But a collector did buy it.

TG. How do you display it? This is like a toilet paper version of a Chinese scroll.

BC. Yes. Exactly.

TG. As in a scroll are you meant to roll it on and just look at it section by section?

BC. It has been exhibited several times. The first time I put it under glass. In a Vargas joint exhibition called Lupa it was exhibited in full under glass frames.

TG. Does the landscape change much?

BC. Mainly flat with some bushes. That is how Luisita is – flat farm land. We went there to see and we talked to some farmers when we were there. At this time I was in a collective called Tutok. “Tutok” is a Tagalog word for focus. This was the time of the Gloria Macapagal Arroyo presidency (2001-10). A time when the number of people who were “disappeared” escalated. The collective was a response to that. It was active from 2006 through 2009 I think. We would exhibit at universities.

TG. Were you showing text works or posters?

BC. Installations. That was what I was mainly doing then.

TG. Was there a leader or the collective was antithetical to such persons?

BC. There was a core group.

TG. Have others from the group gone on to make a name as individual artists?

BC. Among the core group were Jose Tence Ruiz, Manny Garibay, Karen Flores, Noel Cuizon, Iggy Rodriquez,, among others. Me, J Pacena, Mark Salvatus, and others became part of the core group later on.

TG. And why did it stop, or did you leave?

BC. We were all volunteers working for a common cause. But after I was terminated at UST I had to concentrate on getting work for my family. We had big projects at Tutok and then we got tired. One work I did was the mourning pins. It put the number of the desaparecidos on my T-shirt but I also realised that this number just kept getting bigger and nothing happened. What was the group for? Later on my question became, “Are we finding alternatives or other forms? But we end up showing paintings at the galleries. What does that do?

TG. We were talking about Victor Burgin and his move from being a quite strident left wing activist artist to working in a much more restrained, academic even-handed way where you accept you can’t change what happens in the street but you can maybe change in more subtle ways how people think. Influenced by Gramsci, Althusser and other neo-Marxists, Burgin would have said that what mattered was “ideological discussion.” That art works at a level of ideology, it can help us be aware of the late-capitalist ideology we live within.[3] Is that how you feel now?

BC. I think so. I haven’t lost the cause, I am just finding a different way, a different medium.

TG. Landscape Eternal 4 from 2012 is a fully blown landscape painting.

Buen Calubayan, Landscape Eternal 4, 2012, Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches.

Buen Calubayan, Landscape Eternal 4, 2012, Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches.

BC. This painting was shown in the Met. [Metropolitan Museum, Manila] in a mixed show of contemporary Filipino art. This painting references the Ampatuan massacre in Mindanao.[4] It is a proper landscape with dead people. They are taken from actual photographs of the massacre scene. It is a way of saying that the institutions and mechanisms that produces such landscapes as pictures are the same institutions and mechanisms that kill people.

TG. There is a Dutch artist called Armando[5] who starting in 1973 made a whole series of paintings and drawings called guilty landscape (Schuldige Landschaft). As a child he had grown up in Amersfoort near a Nazi transit camp where prisoners were gathered before being sent to concentration camps. The landscape for him was always associated with massacres. The landscape observes evil things but does not intervene. Your painting is of a Schuldige Landschaft too.

BC. Yes.

TG. Was this a turn off for your collectors?

BC. No, they bought it immediately. But as with my mourning pins, I don’t want to exploit such images. It is the inevitable dilemma of the social realist.

TG. Social Realists can also be very preachy, which is a turn off.

BC. I don’t want that either. That is specifically what I don’t want to do: make figure paintings which tell you this is a very bad thing.

TG. And having agreed it is a very bad thing we can sit comfortably and smug.

BC. I want to look for the systems embedded in these images. That is why I am doing diagrams now. What is behind all this? I also did not have dead figures in the later paintings.

TG. Even in the 2012 painting it was not immediately obvious there were dead bodies there. One of the curiosities of your career is that for someone whose work has a strong – I won’t use the word “didactic”- but theoretical, philosophical element you make full bodied painterly paintings that collectors respond to.

BC. Yes. This is true. But my exhibitions always show the links between the different elements of my project. The paintings are the element that can be bought. The diagrams, the archival works, the installation pieces are not easily sold or collected, but they are all part of my system. I want to show the system, the diagrams at work. It is frustrating that collectors only see my work as painting. The work is reduced to one object or one image.

TG. You try to combine the elements: for example, when I showed one of your Spolarium paintings in Slovakia right beside it was a text in English and Slovakian discussing the work. You often install paintings in a way that is annoying but forces you to think: why all this text? Why are the paintings on the racks in the storage area? There is a constant drive in your work to entangle the paintings with the more avowedly theoretical works. We could say you seek to problematise them.

Nevertheless, looking at the paintings as paintings, there is nothing else like them in the Philippines. When you started painting were there Filipino painters you looked to as models?

BC. Yes, of course, Juan Luna and Felix Hidalgo! I also remember looking at early Barrioquintos. I also look at the delicious prospect of Turner, Sargent, and Van Gogh in terms of style and atmosphere. If I may also add: Cecily Brown, Anselm Kiefer, and Cy Twombly.

TG. I mentioned that the toilet paper drawing looks like a Dutch landscape as Rembrandt made it. Other more turbulent paintings remind me of Jacob Ruisdael’s Jewish Cemetery. Very dark, gloomy, cascading water.

BC. I did study the work of Rembrandt as well as Turner. I think the problems we are facing in society are very basic. If one thing or medium does not work we tend to just go find another one. But I think we have to still work on some basic stuff. I think painting is one of these basic mediums. A basic thing that people still understand. People still use that language. That is also why I have to take it apart.

TG. You have to deconstruct the history of painting.

BC. In a way, yes. It is the same framework. We can dismantle academic paintings to think out of the box only to find we are still in the box. Even if you have instructions on how to get out of the box it is still a box.

TG. When you make paintings that try and dismantle or deconstruct paintings you are still within painting, still within that box?

BC. Yes.

TG. We are talking about a painting tradition that was predominantly European. Can I ask: have you ever been to Europe or the US?

BC. Only to Berlin and only for five days.

TG. So your knowledge of Western paintings is almost entirely from reproductions.

BC. I have seen original western paintings in Japan and Australia. I had a residency in Australia in 2014 as a result of winning the Ateneo Art awards.

TG. The year before was when you started making paintings based on Luna’s Spoliarium. How many did you make?

BC. It is a series of eight paintings.

Part Three, at Buen’s house and studio in Quezon City, Metro Manila,

4th August 2024

Buen Calubayan, Spoliarium IV, 2013, Oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm.

Buen Calubayan, Spoliarium IV, 2013, Oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm.

TG. I remember going into the National Museum here in Manila where Luna’s Spoliarium is exhibited and there were about fifty police cadets standing in front of it being given a lecture on patriotism. It is an enormous painting and also a nationalist icon. Dead gladiators being dragged from the Colosseum’s arena to have their armour taken of for re-use being seen as symbolic of Spain’s treatment of Filipino subjects.

BC. People say that. That is what is in the books but my research on Spoliarium, led me to challenge this placement of Luna and Hidalgo[6] as patriotic, nationalist painters. It is said that Luna winning a prize in the salon brought the Filipinos onto equal terms with the Spanish – as good as the coloniser. That is the official line. It’s also framed in the idea of genius. But actually the salon didn’t recognise him as a Filipino. They saw him as a European. He was European enough to win. He had been educated to fit in in Europe. Him making an excessively large painting like Spoliarium was a sign of personal ambition.

TG. And at that time there were many large academic paintings of scenes from antiquity, often with lots of nudity or violence, or both being made for the salons. An artist like Lawrence Alma-Tadema in the UK devoted his whole career to such paintings.

BC. It worked against the colonized in such a way that it only strengthened Europe (as the colonizer) to be the centre of art.

TG. If you were an outsider you had to go to the centre. Luna sought validation first in Spain, then in Paris.

BC. The salon and its paintings never came here. It was always only there.

TG. So making it a nationalist painting was an act of posthumous myth-making.

BC. And what is the salon today? It is the Venice Biennale. We still crave validation from the centre.

TG. Witness the controversy other who gets the Filipino pavilion every two years.

BC. It’s not about Juan Luna or Hidalgo per se. It’s about that incessant craving for international validation. To our longing to be equal to our erstwhile colonisers.

TG. If you go back to that period, you see how desperate artists from Sweden or Finland were to show in the Paris salon. They were as much outsiders then as were the Filipinos – as indeed were artists from the USA. Showing in Paris was the validation they needed to show they too were “real artists.”

Your research project was analysing how and why Juan Luna’s Spoliarium had been mythologized. But what led you to make this series of eight paintings based on it? They are all of details within it. Your Spolarium IV, for example, shows the hand of a dead gladiator and the rope pulling him out of the arena to take his armour off for re-use.

BC. The whole project also intended to dismantle Luna and Hidalgo by way of re-painting them. Imagining them on the bigger picture of the Nineteenth Century, in the context of the globalisation that was beginning then, and the growth of nationalist discourses. I wanted to find where Luna and Hidalgo were really situated – in the bigger picture, not just the salon.

TG. What struck me about Luna having seen the big show of his work in Singapore is that the early paintings such as Spoliarium are far less interesting technically than the later work made in Paris where he became effectively an impressionist painter.

BC. Yes.

TG. To some extent the way you have painted your Spoliarium paintings is how Luna would have painted in his later looser, more impressionist style.

BC. In a way I haven’t really dismantled it (yet). I have used Spoliarium as a base to also seek validation with my own practice within the local art scene. In a way I see them as a performative gesture or strategy similar to how Juan Luna used his painting to seek validation in a larger art scene. The scene today is not so different from the days of the salon. That is the official scene. In juxtaposition to this is my research into the Banahaw for instance in Pasyon and Revolution or the aesthetic sensibility of the Katipunan in, for example, their amulets and the prayers printed on their clothes.

Buen Calubayan, Pasyon and Revolution, 2014.

Buen Calubayan, Pasyon and Revolution, 2014.

TG. So, one day in the future, when you have your retrospective would you like to show Pasyon and Revolution in the same room as your Spoliarium paintings?

BC. Yes. Actually, in the exhibition where I showed Pasyon and Revolution opposite I placed not a Spoliarium painting but a landscape painting that referenced traditional English landscape paintings I had seen on my residency in Australia. The hammock in Pasyon and Revolution was made from the text of the book Pasyon and Revolution (by Reynaldo Ileto. published 1979). I stripped out the text and made it into a very long thread and then I wove it into a hammock.

TG. It must be fragile!

BC. Very fragile! On the clothesline behind are printed prayers in Latin that I collected from Mount Banahaw. One of my intentions was to draw two parallel lines: the salon line and the popular line. The video projects images I took in Mount Banahaw. I want to go back there: it is still ongoing research for me. I always intended to actually live there for two years or so. What I have done so far is not even the first chapter of that work, just a prologue to it. I grew up in a nearby town. My mother would not allow me to go there because of the strange religious sects based there. Perhaps my parents who are staunch Catholics feared I would be polluted by them. [Laughter] So they were very protective of me.

TG. You initially showed just five of the Spoliarium paintings at the Now Gallery in 2013. You never showed all eight together?

BC. No, they are all privately owned now.

TG. Did you show and more conceptual works with them?

BC. Just the paintings.

TG. This is unusual for you.

BC. Yes. Until 2013 I was a researcher at the National Museum, but my research into Spoliarium is still unfinished. I am still working on it. I want to replicate a very big catalogue that the National Museum published for their inauguration of the Spoliarium but with new texts – and a new tour guide script. Since entrance has become free there are many school trips there.

In the middle of that juxtaposition is my timeline. Relocating myself and the nineteenth century things. That is being updated too. It is an ongoing work. Just as the diagrams change all the time.

TG. Can people see your timeline on the web or is it a physical object you exhibit?

BC. It was uploaded to the website of NTU CCA in Singapore when I had a residency there. It is the spine to all my work. I am adding to it and also recontextualising it.

TG. I sometimes think you are a secret encyclopaedia maker: you want to absorb everything into your project.

BC. I think so. I want to understand the system and connect everything, but in an exhibition some elements must be highlighted and others not.

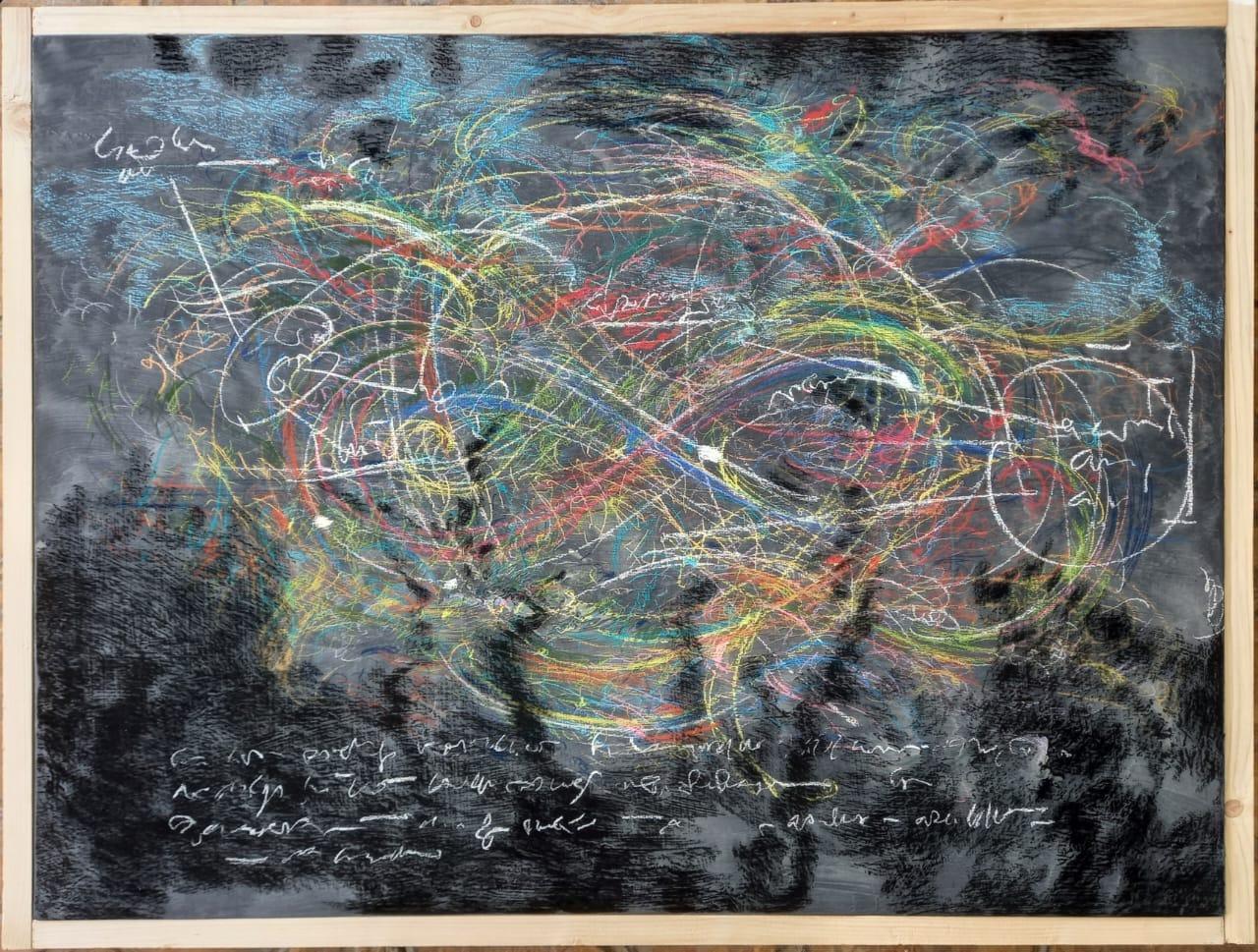

TG. I am thinking about the trajectory of your work and what you have hung on your studio wall today. At first glance it looks like a blackboard with some writing on it, like a Joseph Beuys blackboard. But the writing is more aesthetically pleasing than that of Beuys. It reminds me of Cy Twombly’s blackboard paintings and how he could make scribbles and scrawls look elegant. As you said before we turned the tape on making them is quite complicated: a layer of standard gesso and then a layer of black gesso, a special gesso for pastels, and then the pastels – you have to work out which ones are not changed by the final layer of fixative. This is being sent to Seoul Frieze. There are many words in this piece, but that are all in Tagalog, not a language commonly spoken in South Korea. Will you include a text to be displayed by it.

BC. Yes. Most of the texts are from books I have been reading recently about land struggles, or from the texts we made at the Vargas Museum exhibition. I want to develop readings sessions and workshops exploring these texts. [The last two parts of this interview were in Buen’s new house, designed by himself and his architect sister and brother-in-law. The top floor of the house, with its adjacent roof garden are designed as a site or forum for such sessions or workshops. TG] Or lectures or performances.

TG. But you can’t do that at an art fair like Frieze Seoul.

BC. No, all I can do there is have a short text indicating what the writings are about.

TG. I am also looking at the recent painting you have chosen as an image for this interview – does it have a title?

Buen Calubayan, A Way out of the Wilderness, 2023, 36 x 48 in.

Buen Calubayan, A Way out of the Wilderness, 2023, 36 x 48 in.

BC. The title for that comes from the Vargas exhibition: A Way out of the Wilderness. The writing in this is in English. It references the movement of the landscape. It echoes the sign for infinity. These are also the movements of the body, its rhythms. In a way this is a way to dismantle the diagrams of linear perspective. How we can re-integrate ourselves in the landscape by way of body movements, of experience,

TG. So is the root for these new paintings your diagrams, not a fascination with the blackboards of Beuys, or the ecriture of Cy Twombly?

BC. Yes. The diagrams and the attempt to dismantle one point perspective as a flattening device. I want to find other diagrams that cater to other senses. The one-point perspective is only applicable to the sense of sight. It makes the world flat as an image. And now with all these screen devices we are using one point perspective even more. We have digitalised, pixilated the world and flattened it. This research project is about dismantling the one-point perspective in such a way that we come to understand the world in a more holistic way. Holistic in the sense of being multi-sensory. Understanding the world with all the senses activated. But, of course, the irony is that once I capture such an image it too flattens the experience.

TG. You are re-inscribing the body into your work. But in so doing the re-inscription too becomes only image. It is an inevitable paradox. All you can really do is just keep doing it.

BC. Yes, doing it again. Finding other co-ordinates. With all the senses. Walking, doing work, washing the dishes, these are all part of the everyday rhythm of the body. I see it as a diagram. All these movements.

TG. This also makes me think of contemporary dance. Is dance something that interests you?

BC. Yes. I always dance. I alternate it: I walk, I exercise, I dance.

TG. Do you dance to music or just to body rhythms?

BC. Sometimes to music, sometimes not.

TG. Have you ever brought dance into your exhibitions?

BC. Not yet.

TG. Could you imagine yourself collaborating with a dancer or a choreographer?

BC. I would be open to that. This is one of the directions I can see myself moving in.

TG. Could that lead you to using video too? The problem of involving dance in an exhibition is that the dancers can only be there once.

BC. Right now, I am hesitant to use videos. For the same principle: I see that as yet another flattening device. I am more focussed on the situated experience, which is very hard to show. Dance is pure experience. I mean, if I dance here nobody will see it, it’s for myself and I don’t want to capture it on video or some other flattening device. It’s just the experience. I want the event itself.

TG. There is a wonderful quote from the painter Brice Marden that I sometimes use: “How you look at a painting physically is very important. A good way to approach a painting is to look at it from a distance roughly equal to its height, then double the distance, then go back and look at it in detail where you can begin to answer the questions you’ve posed at each of these various viewing distances. If you go through a museum and you look at a lot of paintings in that way, it’s like a little dance; it’s almost a ritual of involvement.” Sometimes when you look at children looking at a painting you see that they do the same. There is a sense in which painting is connected to dance: it can subtly evoke a dance.

I want to go back to you last show at Blanc gallery where you showed a number of installations and diagrams but also to the shock of everyone nine new large paintings but none shown hung on the wall but on the sliding racks in the gallery’s storage room. On a table nearby there were several books and texts. To see one of the paintings you had to pull it out. And you could only see one at a time. I suppose this is what Bertolt Brecht would call an A effect (Alienation or distancing effect) where something is staged in an unexpected way so the audience’s illusion is broken and they are made aware that what they are seeing is just actors and stage props – or in your case not a romantic landscape but coloured mud on woven fabric in a commercial gallery. The viewer is jolted out of his comfort zone. He or she had to physically pull out the paintings one by one to see them. He or she had to bend down to read the books or texts – no chairs were provided I noted!

Installation of paintings at Buen Calubayan, Blanc Gallery, 2023, with on right Eye level viewpoint, 2023

Installation of paintings at Buen Calubayan, Blanc Gallery, 2023, with on right Eye level viewpoint, 2023

Installation of readings at Buen Calubayan, Blanc Gallery, 2023

Installation of readings at Buen Calubayan, Blanc Gallery, 2023

Then he or she would go upstairs to find enormous diagrams made with stickers on the big windows and also a couple of very austere installations. (I was reminded, by the way, of Giulio Paolini who made austere but elegant installations about perspective and mimesis.) One of the installations was a replica of a grid of lines just above the ground such as farmers put to keep birds away from their crops.

BC. First of all I treated the paintings as an index, installed in the way of a museological installation. It’s a gesture, a way of activating the archive with some movement. Also I was introducing a different way of looking.

Buen Calubayan, Fever as Symptom of Evolution, 48 x 60 inches, Oil on Canvas, 2023

Buen Calubayan, Fever as Symptom of Evolution, 48 x 60 inches, Oil on Canvas, 2023

Buen Calubayan, On Dynamic Unity, 60 x 72.25 inches, Oil on Canvas, 2023

Buen Calubayan, On Dynamic Unity, 60 x 72.25 inches, Oil on Canvas, 2023

BC. The documents and the books there are my research. I don’t expect anyone to read an entire book there. They are like footnotes listing my sources.

TG. This is a very curious idea: an exhibition with footnotes.

BC. Footnotes should be read later, in your home, if you are interested enough to follow up. It is not meant to be read there. My intention is for you to go out of the gallery. I want to say that not all is in here.

In the installation upstairs the grid also refers to one point perspective.

TG. There is a term used by the Soviet artist and photographer Alexander Rodchenko ostranie – making strange. I think that is what you are trying to do: the paintings no longer sit comfortably on the wall. You can only see them by an act of participation.

BC. Yes.

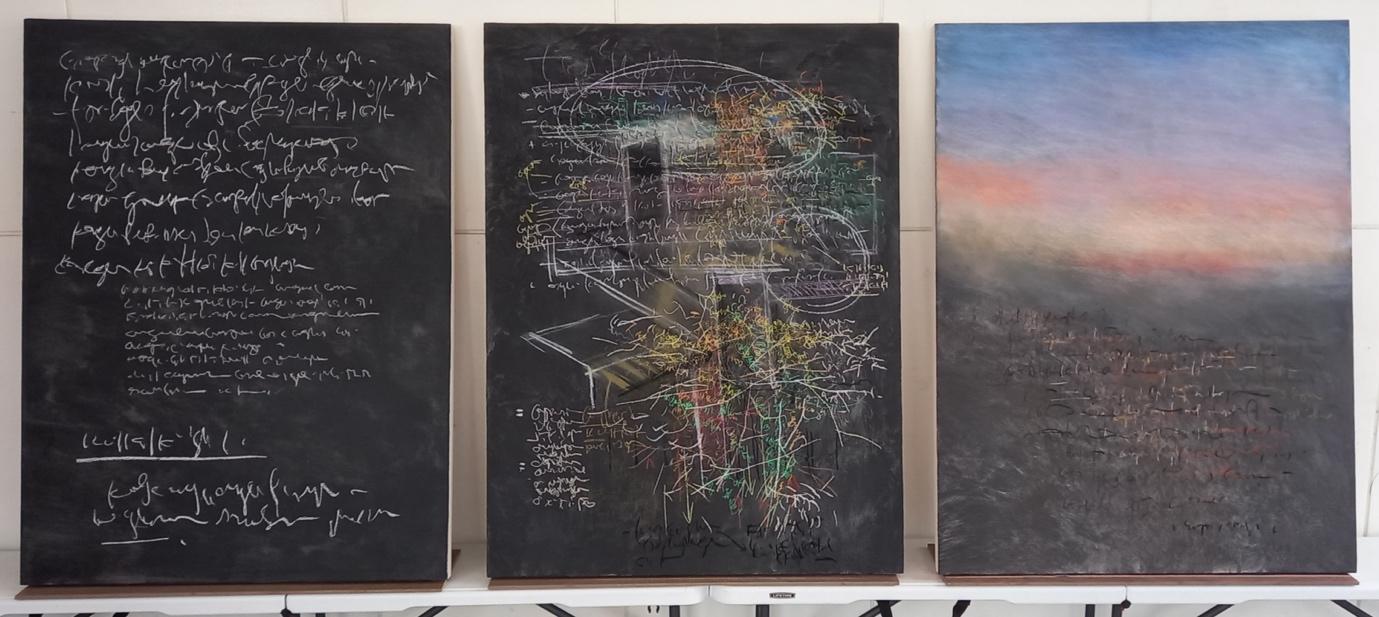

TG. We haven’t discussed your recent triptych Plantscript. Perhaps we could conclude by discussing that?

Buen Calubayan, Plantscript (triptych), 2024

Buen Calubayan, Plantscript (triptych), 2024

BC. There is this lingering phrase that I want to use later on: maybe as an exhibition title, or a performance title. The phrase is “teaching perspective to plants”. It is about observing the movements of plants. This is one of the products of the walks with my dog during the pandemic. And also trying to understand the rhythm of my body in relation with nature, with the world. It is a result of these new diagrams that that I have been discovering or formulating. These are the diagrams at work as a result of the dismantled one-point perspective. Here when I am walking, I am already in nature and then I am avoiding relating to the world around me by using the one-point perspective device. I want to activate the other diagrams that are multi-sensory. I want a holistic approach. This is one such attempt,

TG. In this triptych you progress from writing to writing with a. diagram to writing with what looks like a sunset. Sunset or sunrise?

BC. Both. [laughs] Either. However, I think it is more of a sunset because I never got up early enough for a sunrise. This was shown by Arario Gallery at Art Basel Hong Kong last March. At the moment I have no upcoming solo exhibition, but I send individual works to art fairs.

TG. Is that a problem for you? Recent exhibitions like those at Vargas and Blanc have had a variety of media – painting, installation, diagrams, texts or seminars – but that is not feasible at an art fair. A visitor to Vargas or Blanc had made a specific journey to see your work. We can expect them to give your work some time and concentration. Maybe some will give an hour of their time to your show. But in an art fair you would be very lucky to get more than fifteen seconds of anyone’s attention. Do you just bow to circumstances and get on with it?

BC. It is the system that is in place. It is how the market operates. This is why I want to publish a book: to reach a more receptive audience. Nevertheless, I still hope that my work can be exhibited in museums where it can have deeper and longer exposure. But for now the art fair is a venue and we use it. It is not the only outlet for the work. Other venues will materialise: I have time. I am only forty-four. I have years left to make work in!

- Mark Foster Gage, Aesthetics Equals Politics: New Discourses Across Art, Architecture and Philosophy. MIT Press, 2019 ↑

- The term used in the Philippines for a student’s completed exercise ↑

- See my interview with Burgin can be seen in Block No. 7 Nov 82 and in extracts form in Victor Burgin, Between. Basil Blackwell/ICA. 1986 ↑

- Also known as the Maguindanao massacre. Give details ↑

- Born Herman Dirk van Dodeweerd 1929-2018. Involved in the Situationist Group. A member of Nul group. Well known in Holland and Germany but little seen elsewhere. Founded his own museum which has now closed due to lack of funds. ↑

- Hidalgo., see Jill Paz interview on this website ↑