Tony Godfrey. Hi Jill. I have to admit this feels a bit weird and disembodied. I enjoy the experience of sitting opposite the person I am interviewing or sitting next to them when we talked in public last year at ALT art fair.

But the pandemic keeps us at home, stuck to our laptops. So here I am at my desk, on my own typing away. What are you up to? How are you?

Jill Paz. I am drinking coffee and the energy of my home/studio space has become nervous anxiety as I prepare for international travel, not knowing what to expect with all the govt. protocols in the USA and, on my return, the Philippines

TG. Of course, you are just about to fly back to the USA for two months. What will you be doing and seeing there? Whenever I go back to the UK, apart from seeing my children and friends, drinking warm beer and eating English fish and chips I spend as much time in museums as I can. Having lived in London I am used to seeing a lot of art – old art, international contemporary art. I really miss now that I live in the Philippines.

JP. I am traveling with my husband Seth and we will be visiting his family in the Midwest – in Columbus Ohio. Both his parents are ceramicists, each with their own studios and distinct styles. I love attending art residencies and for me, this summer back in the States, hanging out with ceramicists, seems like a perfect place to learn this medium and take on my own personal residency.

Yes, returning home, though Manila is also my home, but returning to my other home, where I grew up, in North America, I do just that. Drink beer (though not warm, and also not with ice cubes as they seem to do in Southeast Asia), eat burgers, and visit museums in NYC if I have a chance. I really miss those days. I lived in NYC for a moment during undergraduate school days. I think I must have spent half my time just visiting museums, galleries, artist studios.

During the lockdown I have been reading a lot of Alice Munro, and mixed in, politics in America, I just finished After the Fall by Ben Rhodes, which looks at democracy in America, among other things. It doesn’t seem necessary to read Stephen King anymore when just reading and listening to America’s political climate can bring chills!

TG. Drinking beer with ice in is one of the most horrible things about South-east Asia! US politics is truly terrifying at the moment and must be especially so to someone like you – a first generation immigrant and a person of what you Americans call “of color”.

JP. Yes, US politics is truly terrifying. In the past few months, there has been anti-Asian hate crimes aside from these debates on critical race theory. Aside from being cautious on mask wearing and social distancing, I need to take that into consideration.

I have been thinking of that actually, what it means to be a first generation immigrant and a person of color. Not to mention that I come from the Philippines, a country colonized by the States.

TG. You tell me this exhibition will be the first time you have exhibited drawings. What led you to do this?

JP. When Manila went into lockdown in March 2020, I was all of a sudden stuck at home. And then the same thing that happened to the whole world is that we were secluded in our domestic bubbles. My home in Manila, or to be more specific, in Quezon City, is a fairly decent sized condo, but my art studio is located in Silang Cavite, which for months I was not able to visit. Getting back to drawing, a practice that I have not frequented since art school in the early 2000’s, really began as a reprieve from everyday home life. I even started to bake bread at home and cook!

TG. I have been baking bread too during the lockdown! And reading lots: the lockdown has been so strict and prolonged in the Philippines.

Presumably, being as you were locked down in the Philippines, you drew from images on the internet or in a book.

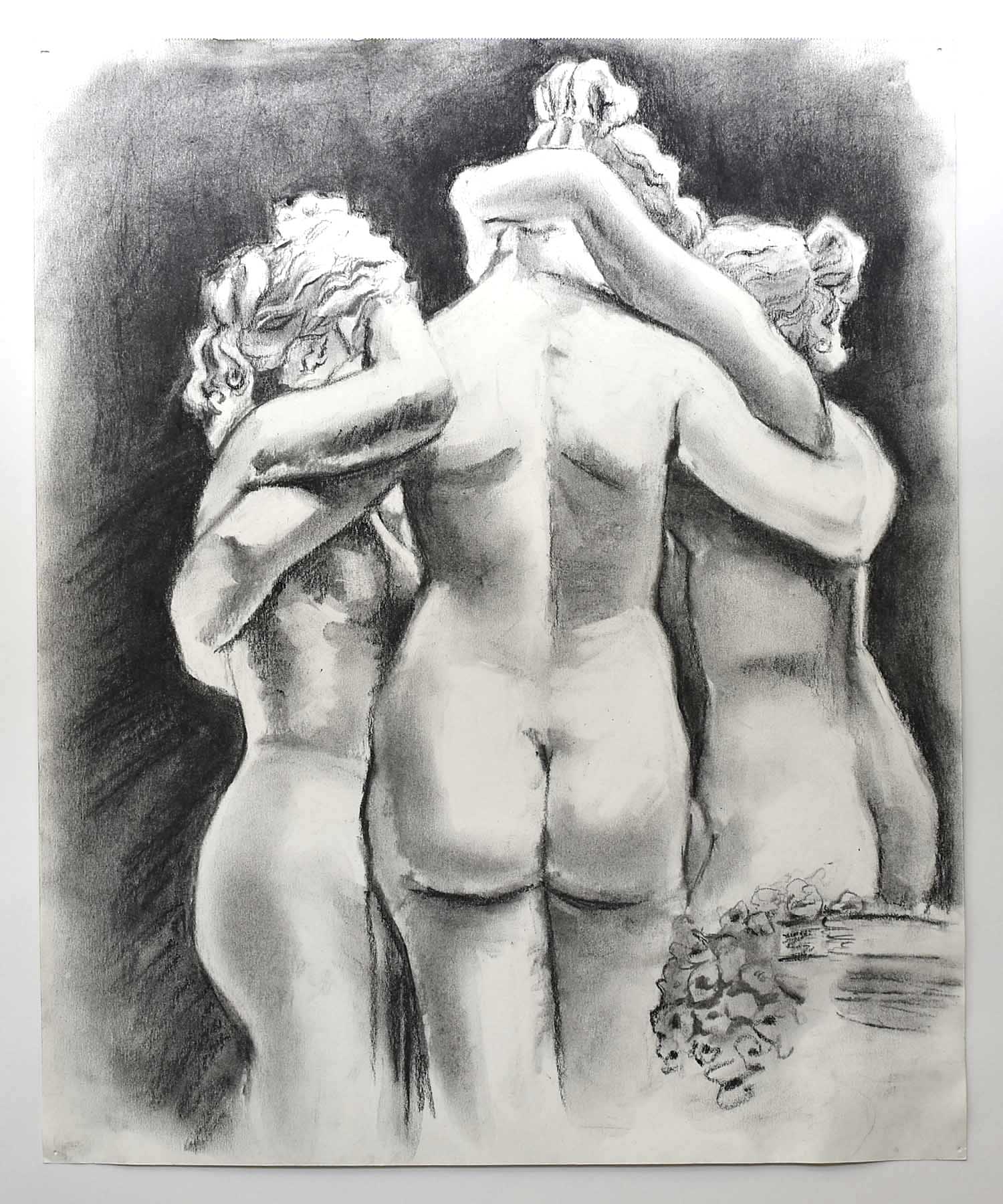

JP. The drawings are from photographs on the internet. I was thinking of Remediation in art, which is the act of transferring the affects of one medium onto another. The all-around views of ‘Three Graces’ that I have been drawing and painting recently, look at the connection and relationship of photography and sculpture, and in particular the methods used by archaeologists in the Nineteenth century: photographs of 360 degree panoramic views to reveal and show the physical tangible. Put another way, this method of archaeological illustrations creates an illusion of dimensionality, an image revolving in space.

TG. Which particular sculpture was it you drew from?

JP. The drawings are based on the classical sculpture Three Graces. Also due to the lockdown and this subsequent desire to travel and see art in person, I would visit the online viewing rooms that became and continue to be more readily available nowadays in museums and gallery websites. I was drawn to the subject matter of the Three Graces. This work of art and subject matter has been explored and depicted in dozens of paintings and sculptures, from artists like Peter Paul Rubens, Raphael, Botticelli, who all took up this motif to express notions about pleasure and relationships with one another. The comforting gaze, the embodiment of charm, beauty and creativity – I wondered what these age old tropes embody for us at this current time?

TG. Botticelli, Raphael, Rubens. These are all men, of course. In their time you would have rarely, if ever, seen a women drawing there. Or, indeed in the life room. The life room was exclusively for men.

JP. Yes that these disciplines – sculpture, painting, drawing – unlike the subject matter! – are embodied as male, just goes to show how women have historically been stuck between allegory and a hard place. Now I cannot recall the female historian/critic who said this, but she said something along the lines that if women are to be part of art history, then all of it needs to be rewritten! I am, of course partial to that idea, of redefining, repairing our histories to be more inclusive. Remediation often has a political aspect, upturning accepted ideologies, be they racist, sexist, whatever.

TG. You were a little hesitant to show the drawings at first. The “real works” are the laser cut pieces derived from them – do we call them drawings or sculptures or paintings? or indeed photographs! But I think to see them together will make clearer that your overall project is about “remediation” – and also in a complex way about archeology.

JP. I tend to call the laser cut pieces ‘paintings’. (Do you?) Yes, I was hesitant to show the drawings. I think I still am actually but I am comfortable, perhaps even confident, that together with the wood panel pieces, the idea of remediation will become explicit.

TG. We will return to the idea (and politics) of remediation in a while. But first, can you fill in your background a bit. You left the Philippines when you were a year old. Can you tell me something about your life in the USA. What did your parents do? Which town and state did you grow up in? Where did you go to college? And what did you study?

JP. I am Canadian American Filipina, that is I grew up in North America but I was born here. Though I had no memory of leaving Manila at age 1, it was 1983 or 84 and my family was seeking to fulfill an American dream, I visited Manila several times throughout my childhood and had a connection to it, the stories shared with me were an alarming paradox of romanticized nostalgic heydays of the 60s and 70s mixed with utter disdain with the government (I remember being on the front page of the University paper in Columbus in the 80’s, I was just a toddler, bundled up in a blue coat with bunny ears, and holding a picket sign in protest of Marcos regime, seems like a good way to get some publicity).

In my understanding, I saw what the writer Nick Joaquin wrote, about this city being in ever-greening, ever-decaying. I remember for example a visit to Manila in the 90s and seeing the MRT trains building up along EDSA, the construction was truly a grand modernist feat, despite it taking longer than usual, the city and country was at a full speed toward modernism, but it seemed to me that this trajectory was on parallel with tyranny.

I grew up in Columbus Ohio, and then spent grade school years in Toronto, Ontario and then mostly Vancouver, BC, Canada, until we moved back to Columbus. When I moved out, I first tried out NYC and then went back to Pacific Northwest, to Vancouver and then Portland Oregon. A couple things about that–we moved a lot simply because my parents wanted to. My parents were architects and though I did not want to study architecture, I liked learning about its history and was inspired by it – the first images I sent you of the hanging mobile sculptures were drawn on Architecture programs.

I studied art at several schools, from a private art college in the Midwest, Columbus College of Art and Design, it was their first year offering full scholarships to international students and I was fortunate to be the first beneficiary, to finishing up at Parsons in NYC and then taking up art history at the University of British Columbia, where I also landed my first job as an assistant at the Museum of Anthropology. I was fond of arts admin work, and felt like my calling was there, I had several years of experience teaching art from elementary to college level during graduate school. It was not until 2012 that I actually decided to get back to my own art studio practice, I began an MFA program at my alma mater, where I again received a scholarship to study. Higher education in the States is costly and I cannot imagine having been able to afford it without my scholarships.

I was considering pursuing a position as an adjunct professor in 2016, but I was exhausted with being in school! Instead I spent months going from one residency to the next, from the Catskills in NY to the Banff Centre in Canada and then to Dresden, Germany. In 2017, Seth and I moved to Manila, because my mother had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease and I am the only child.

TG. You have a Filipino sense of filial duty!

JP. And so this whole mothering from a distance in the States was not enough, and I had to be in the same city with her to oversee her healthcare. And that brings us up to the present moment where am I am now, here in my condominium in Manila.

TG. This sculpture from 2004 may have been made on an architecture programme but it avowedly references Mona Hatoum, an artist whose work is always very personal – dealing with issues of childhood, pain, isolation, the female body. So was your work although looking very constructivist also in some way personal?

JP. After Mona Hatoum (Crib), takes Mona Hatoum’s iconic sculpture from 1994 – Silence – a life-size glass crib. I may have not known these facts of the artist’s personal history back then, I honestly cannot remember, but there was something about Hatoum’s sculpture, the feeling of it, the hostility, and also the comforting, and then displaced sort of vibe that I get from her work, that was something I may have been unconsciously exploring then.

I have included images of both Avid Present Dense Intense, 2011-2012 and After Mona Hatoum (Crib), 2004, because my work continues that path. I often begin from an extreme personal close-up of my life, entering my work from there and then stretching to involve a more expanded view of history and the world. I like the idea of an artist or individual mining their own histories, finding things that may have been overlooked and finding inspiration from that, to make sense of the world. At the same time, these sculptures were done in a process that begins with a computer rendering. There is a duality to my work, of analog and digital, human and machine, and recently, my take on repair and preservation in the works that looks at Hidalgo’s destroyed paintings. And another thing, I am a fan of the unoriginal, of extracting something from an already identifiable existing object.

TG. This is very interesting! I have always sensed that though your work seems quite analytical and dispassionate that it is always about, however elliptically presented, a personal life. Does Avid Present Dense Intense still exist – or only the documentation of it? Indeed can it only ever exist except as the photograph of it when the sticks are in perfect alignment?

JP. The process in Avid Present Dense Intense is a systematic approach of a pictorial world. Also I think I may have taken that term from the David Salle book How to See when he was describing the artworks Roy Lichtenstein, who funny enough, and I am guilty here of speaking in tangents, Lichtenstein’s was the first art exhibition I remember seeing back in Columbus Ohio.

OK! back to your question. I do not think Avid Present Dense Intense still exists, though the files most probably are in my old hard drive. During the move to Manila, I seemed to have misplaced objects from artworks to shoes.

As for the sculpture’s existence, or rather its perfect alignment coming together only in the view frame of a camera, that brings it back to its original state, which is a computer rendering.

Let me also mention the artists that I gravitate to, aside from Mona Hatoum, I go back often to the strange curious works of Rosemarie Trockel, Martha Rosler’s collages and videos of women’s roles, the Minimalist Ab Ex paintings of Agnes Martin, the xerox copies of Barbara T., Smith, Doris Salcedo’s counter monuments to power that is both personal and Conceptual in its making process. I also like Sheila Hicks, her craft to art to craft sort of installation.

TG. Revealing choices! Trockel’s work is frequently incomprehensible to me and then she will make something so precise and unsettling. Martin, Salcedo, These are understated but tense artists. [There is a very good biography of Agnes Martin incidentally!]

JP. I like the term ‘Romantic Conceptualism’ to describe my work. Does this exist already to describe artworks?

TG. Bas Jan Ader has been described as a romantic conceptualist – the Dutch artist whose work was about falling and who disappeared at sea.

JP. That’s right, his work has described as that. I do like the work of Bas Jan Ader. I’m partial to artists who work in photography, using that medium to document sculpture, performance art, and land art.

TG. So we come to Hidalgo and your works from 2014 onwards. You told me you would normally return with your family once a year and would stay for a month or so in the old family house, where there were many paintings and drawings by your great grand uncle, the artist Félix Resurrecíon Hidalgo, seen with Juan Luna as the founder of Filipino painting. Sadly, many of the paintings in the family’s Manila house were destroyed or damaged when the Japanese commandeered the house as an HQ. Paintings by him in other houses were destroyed in the battle of Manila – when the city became the most devastated city in the world after Warsaw.

Making paintings – do we call them paintings? – from Hidalgo: was this to do, however indirectly, with your childhood?

JP. Visiting my grandfather’s home and getting to experience that place where the living and dining rooms were lined with our ancestor’s paintings was truly inspiring. However, from my childhood memory, some rooms and parts of that home are akin to how Miss Havisham’s house in Great Expectations was portrayed. Another element of that house is that it was believed to be a radio headquarters for the Japanese army during the Second World War. Before getting forced out of his own home, my grandfather saved the paintings bequeathed to him by Hidalgo: he took them up to a mountainside for safe keeping, there it was kept away for years. One of the rooms of the house used to be filled with charcoal drawings, sketches for the La Barca de Aqueronte painting, of Charon, the boatman to Hades. From that room, a spiral staircase leads down to the basement, where behind the bookshelves exists a tunnel and bunker. Its opening is filled in with concrete but it’s still there up to now.

To get back to my work, I included the cardboard painting Untitled (After Hidalgo, Libertatem), 2014. This was actually my first painting made on cardboard using the mark making of a laser machine and made during graduate school. And funnily enough, I decided to use this image, of Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo’s Per Pacem et Libertatem (Through Peace and Liberty), an allegorical painting depicting conditions of peace and liberty in the Philippines under American sovereignty. The painting shows Filipinas offering to America an olive branch symbolic of peace and homage. The original life-size painting, completed in 1904, was exhibited in the St. Louis World’s Fair. The painting then returned to Manila and sadly was burned and totally destroyed during the liberation of Manila in 1945. Sketches of this painting were also in my grandfather’s home in Manila.

Something I kept going back to in my art are questions on repair–What goes missing when a home, a person, or a society becomes renovated? What pulses behind the desire to re-build, or create an otherwise new veneer? And in what ways does the skeleton of the old inform the flesh of the new?

Since making Untitled (After Hidalgo, Libertatem), 2014, I often go back to this: the need for and subsequent limitation to repair and renovation.

TG. Was this painting on any old cardboard or were you using unfolded balikbayan boxes for it? If Hidalgo is high Filipino culture, the balikbayan box is everyday Filipino culture.

JP. This painting was just on cardboard, not Balikbayan box cardboard. That’s a good way of stating that.

TG. When did you start using balikbayan boxes? But, Stop! I can hear a reader asking, “What is a balikbayan box?” I should explain! There are five million or more Filipinos working overseas – OFWs or Overseas Foreign Workers. The money they send back is vital to the economy of the Philippines. There is also a well-developed scheme for sending stuff back to: cardboard balikbayan boxes are given to the senders as kits to unfold, refold and tape together, then fill with toys, foodstuffs, candies and other luxuries to send to their relatives back home. People who send them (including myself whenever I am back in the UK) pride themselves on packing them well and squeezing in as much as possible. For the recipients unpacking a box is normally a family affair, the sender hopefully remembering all their relatives.

JP. I often say that the balikbayan box is the ubiquitous symbol of the Philippine diaspora.

I started using balikbayan boxes around 2014 with used balikbayan boxes that I had. The initial piece It’s a Journey Back that I’m Always Taking (Balikbayan Box), 2015, was from a recycled box that was returned to my US address. The box represents something unique to the angst and energy of this paradoxical relationship of being a Balikbayan here in Manila. It represents both engagement and estrangement. During the last 15 months, I’ve come across op ed articles, particularly in the Post and the NYTimes, stories of family members, couples, friends, strained and surviving apart. The longing for one another, of feeling displaced, and in some cases, mothering from a distance, is a common facet of life for a Balikbayan. Not only do immigrants carry a feeling of being both being engaged and estranged, but they also continue a performance of diasporic intimacy. The Balikbayan boxes tapped that identity, that technology of translocality. And similar to the works of artists I mentioned such as Salcedo and Hatoum, evoked a melancholy evident in the lives of those living apart.

The distinctive markings that the optical tool of a laser machine made on the medium of cardboard was happenstance in a way. But I was quick to see that in the breakdown of material, the way a laser can burn a mark onto a cardboard, was a sort of art trope that I wanted to explore. It really has been an exploration of the process, as well as the hierarchy of painting and the mundane banality of material.

TG. Am I correct in saying that It’s a Journey Back that I’m Always Taking (Balikbayan Box) was the only one of these pieces to be shown re-assembled as a box? All the others, I am not sure how many you have made since then have been displayed flat against the wall. Were all of them after 2015 made on unfolded balikbayan boxes? And did all of them have images taken from Hidalgo paintings laser-cut or etched into them? This piece if I remember correctly has an interior etched inside it – the interior of Hidalgo’s house.

JP. Yes correct, It’s a Journey Back that I’m Always Taking (Balikbayan Box) was the only one of these pieces shown re-assembled as a box and all of the works in cardboard after 2015, were installed on the wall – like paintings.

Though I moved to Manila in 2017, I did not set up a studio space in Silang till the following year. I mostly lived there in Silang in 2018, taking walks each day around the neighborhood. This inspired me to make a body of work that I exhibited at 1335 MABINI in September 2018. Drawing from my daily experience compelled me to look at the genre of landscapes–in a way, I was trying to reorient myself and the landscape subject matter seemed fitting. From an outsider’s perspective, it was alarming to see the juxtaposition of skyscrapers next to slums, and peppered in all this is nature—a tropical jungle interlaced into every crack and corner of the urban jungle.

TG. I want to ask about the work shown in 2018 and subsequently, but two questions first: Going back to the box when I showed it in an exhibition in Slovakia that I curated I did not also show the video piece. Should I have? Do you see that as an integral part of the work? Secondly, is the work from 2016 you have chosen – Untitled #12 – atypical or one of a larger series I do not know of? Works that are distressed like so much of your work, but essentially abstract?

JP. In response to your first question: the box and video do not need to be together. I wanted to include an image of the video just prior to the last image I included in the PDF from 2016, because in my personal timeline, that video’s mapping from the US to Manila, is intrinsic to my move or return migration to Manila. Though the video lacks a refined aesthetic of a videographer, there is something haunting or foreboding about its non-narrative documentation.

Untitled #12, from 2016, was made during a summer and autumn residency in Dresden Germany that year. Here is a link to my website of the Vector paintings:

https://jillpaz.com/works/vector-paintings. They are distressed as you stated, but no, they are not abstract. The image is actually taken from a single scanned photograph of a crumpled piece of paper, blown up, and copied, re-photographed and then though painterly in appearance, burned into the canvas or Belgian linen by a laser machine. I was repeating the rasterizing or burning/etching process on successive areas of the canvas, for the larger scroll-like canvases, and allowing for imperfections to creep into this precise mode of technology. I am fascinated with how images traverse our visual and material culture. And when it comes to my paintings, I am questioning the very idea of painting itself, which falls within a longstanding artistic reconsideration of the idea of what a painting entails.

TG. How do you view Hidalgo’s paintings aesthetically? What did they entail at the time? What do they entail today? I remember you telling me your unease that in the Philippines he is seen as a Great Master, but in Art History as written in the West he is not even a footnote.

JP. There are several rooms in the National Gallery Singapore that showcase South-east Asian artists from the 19th century–a period of colonization in the Philippines. It was surprising to see the amount of work that depicted romantic landscapes, a subject matter that did not speak of the trials and burdens of European colonization. Since I have been focused on my ancestor’s work these past few years, I realize now that Hidalgo touched on the subject at least once, and not inadvertently, with the painting The Assassination of Governor General Bustamante, which is on permanent display at the National Museum here in Manila.

Aesthetically, I find Hidalgo’s work appealing and made with an Academic hand. To be honest, his work made in the Neoclassical style, of ‘La Barca’ for example, was a bit dated. However the landscape and seascape paintings and sketches of the early 20th century begin to reveal a painter more confident and looser on his brushwork. In the bigger picture, he was not written into Art History; he is a marginalized figure even here in the Philippines next to his counterpart, the painter Juan Luna. In the Frick Collection library in NYC, where I spent an afternoon searching for his name in the 19th century books that documented the salons of Paris all I was able to find was a single phrase that mentioned his name.

TG. So you are more interested in calling attention to him as a neglected artist, like most artists working on the geographical periphery, than critiquing him?

JP. Yes I am more interested in calling attention to him as a neglected artist. From a personal point of view, my works that take his destroyed paintings as compositions and subject matter is a way for me to unearth marginalized stories that are overlooked, while also understanding more of my own history and culture in the process.

TG. You have a one-woman show coming up at Silverlens gallery in Manila. Are your concerns and methods the same? Which work would you like to show me from that show?

JP. Yes I have an exhibition coming up at Silverlens opening September 9th, a little before the Singapore exhibition. I think the concerns and methods follow the path, process and trajectory of my themes.

I have a statement or blurb for that exhibition: Recently I have been exploring the abstractions, repetitions, and systems of our everyday lives that often get neglected. My domestic life has been magnified in the midst of this pandemic; and though I am not seeking an overtly personal project, my starting point is the pre-existing composition of my ancestral home. From there, I am extracting something new from identifiable objects, as well as textile grid patterns that are deeply rooted in the history of Modernism and Abstraction. By exploring formalist tensions and the breakdown of material, I continue to ask myself: what is the meaning of repair and preservation? And what does it mean to craft a visual vocabulary that speaks of formal elements such as repetition and the slow time of domesticity? The new body of work titled Domestic Abstractions consists of 20 intimately scaled panel paintings. Each painting has an intricately detailed surface, made by the digital optical tool of a laser machine and then layered with acrylic washes on top of a gesso ground. This rigorous consistency of the framework appears to be a conceptual process, but within these systematic conditions opens up the possibilities of exploring a pictorial world.

TG. What about the future? Do have ideas on what comes next. Will you try and work with ceramics when you return to the Philippines in September? And will you do what you spoken of before: move to the country? I think like many other people you find the noise, pollution, traffic jams and general over-crowding just too much!

JP. Since the lockdown and getting stuck in our domestic bubble in the city, I have been dreaming of being out in nature. I’ve been making plans to build a house on a piece of land that I purchased a few years ago in Silang Cavite. In the meantime, our architect, who also happens to be my dad, has completed the blueprint and is getting involved with finding the materials and engineering of the house. I’m just waiting out this rainy season for construction to begin. Hopefully the Philippines will be looking safer from this pandemic too.

Perhaps I might even make an additional space for a ceramics studio.

As for this summer back in the States, I am pretty excited and also nervous. Travel has never looked so meticulous and finicky. But having the opportunity to learn ceramics in Columbus will be such a treat. I often come into my studio with a set of guidelines for how to start; but coming into ceramics, I have no idea where to begin. Perhaps the potential for art is in those fallible attempts.