MARK VALENZUELA INTERVIEWED BY TONY GODFREY

By email

PART ONE: 11-14.8.24

TG. Hi Mark, it was good seeing you last month by Pablo Capati’s kiln in Batangas. Of course, I was not there when the kiln was emptied. What did you put in to fire? How did it come out?

MV. In response to your question, it was a great firing. We fired the kiln for sixty hours at least, taking shifts. I didn’t place too many of my own works in the kiln. I ended up drawing in underglaze pencil on clay forms made by some of the other artists. Anagama firings are always collaborative acts, and so I used the making process to extend the artistic collaboration rather than making my own individual works. I was also interested in the effects of anagama wood-firing on the underglaze pencil. I thought the drawings and markings might disappear when subjected to such a high temperature and long firing, because the underglaze pencils usually tolerate a lower temperature. However, it came out really well. I might consider doing this again in my own practice.

TG. Do you have any images of those collaborative pieces your fired? It would be great to see some? Did you or Pablo take photos?

Before the firing

Before the firing

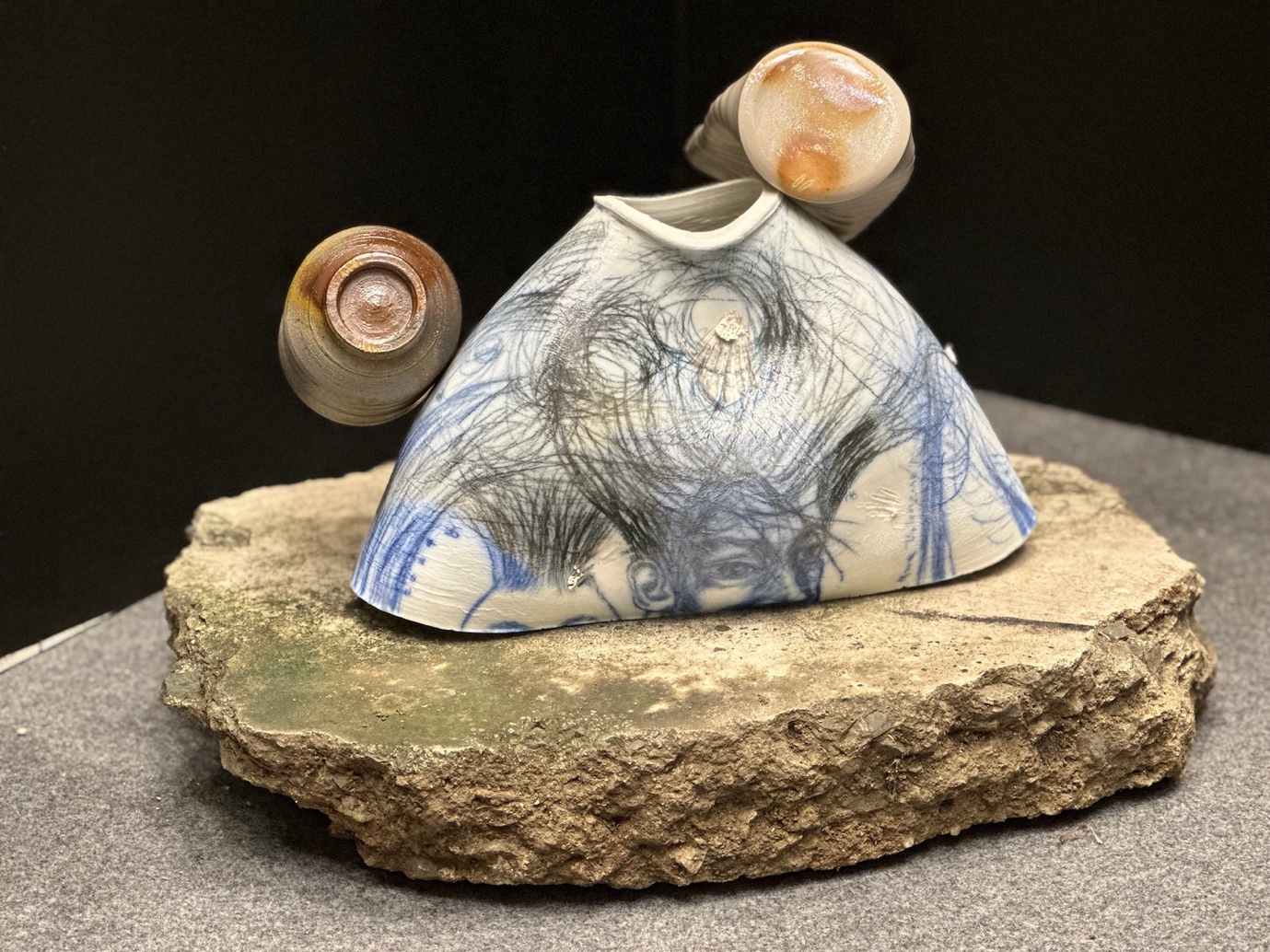

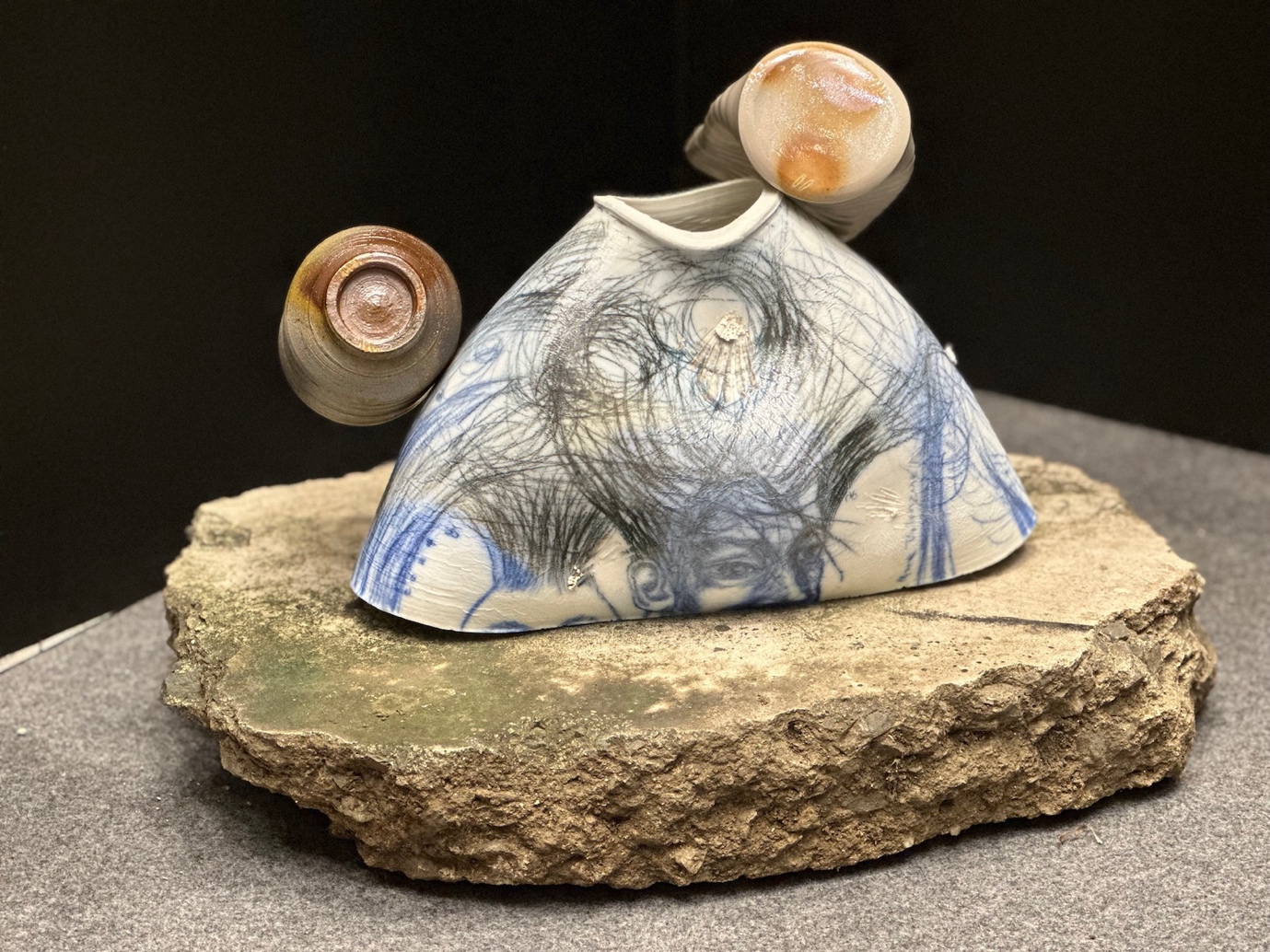

The final work after the anagama firing where other works from other artists got stuck on MV’s work. Some underglaze pencil lines turned blue instead of just black due to very high temperature and reduction. The collaborative work with Alvin Tan Tech Heng (thrown body) plus Paolo Lozano and Ella Mendoza’s cups that got stuck after firing.

After the firing. A collaboration by Pablo Capati and MV

After the firing. A collaboration by Pablo Capati and MV

A small blue jar by Pablo Capati with MV drawings on it. The photo was taken in MV’s studio installed with his other ceramic works with underglaze pencil

In talking about your work there are two issues to deal with. Firstly, that your installations often use many different elements and to illustrate them properly takes many photos! In your recent monograph one multi-part piece Once Bitten, Twice Shy gets 13 separate images! Secondly, that monograph deals with your work from 2015-2022 in some detail so I am going to suggest we deal with maybe just three works from that period: New Folk Heroes, 2017, Tambay, 2019 and Still tied to a tree 2022 and put more emphasis on your early work and your work of the last two years, Are you OK with that?

Or, to put it another way, the book illustrates almost nothing you made before 2013. It concentrates on your Australian years. But looking at the chronology in that book you seem to have been very busy in those early years! By 2012 you had had six one person show and been in at least 22 group exhibitions. I am sure there were some things worth talking about in them.

MV. Sure, I’m happy to focus on works not covered by the monograph, before 2015 and after 2022. Part of the reason the book has so many images of more recent works is that my early exhibitions weren’t well documented and we didn’t have many printable images. My partner Anna’s essay talks a little about my first solo show, but you will notice that the images have been printed quite small to retain the resolution.

However, I think the years you suggest (pre-2015 and post 2022) would be interesting because in the early years I was just starting to experiment with installation-based practice, but the various disciplines I was working in (painting, drawing, sculpture) were not very integrated. Over the years, I have increasingly integrated the materials I work with and become more ambitious in my approach to space and installation. So, there is quite a contrast there. Also, the early years remain interesting to me because that is when I was sourcing my own clay and making use of the local resources in Dumaguete. This period really established my love and understanding of ceramics. Anyway, I may be getting ahead of myself. I would be happy to talk about any of my early works/exhibitions – probably my solo shows are more interesting, because group exhibitions during that period tended to treat my works as individual objects (which even then, I was trying to move away from).

TG. It’s great that you agree! But before we delve into your ancient history can we firmly place you as you are now, in Australia, far from Dumaguete? What is in your studio, what are you working on this moment?

MV. I’m currently working on a small project for an upcoming event in just over a week. It is a collaborative work that will accompany the gig of an Indonesian band called Gabber Modus Operandi. For this, I have reconfigured a steel structure (police hat) that was part of my 2022 exhibition, Still Tied to a Tree. In this iteration of the work, I have bound several ceramic sculptures to the structure using string. I have also created some white panels, which my collaborator Miles Dunne will project a light and video work onto. Please see attached an image of the work in progress.

PART TWO: 16th August 2024

TG. Mark, can we go to the beginning. What sort of family did you come from? What did your parents do? were you brought up in the country or a town?

MV. I was born in Pagadian City in Zamboanga del Sur, Mindanao. I am the eldest of four children. When we were little, my father was a soldier so we moved around a lot, throughout Mindanao. Later on, both my parents became teachers.

TG. What did they teach? at school or college? and when they settled was that in Mindanao? (To which incidentally I have never been.)

MV. My mum taught grade school for many years and just retired last year. My dad taught high school and also retired two years ago. He’s now back in the reservist army.

I think I was around 7 or 8 years old when we stopped living in army base camps and settled in Pagadian City. We moved around a bit within Pagadian City, as there is a military presence in the city and several base camps. My parents stayed in Pagadian from then on, but are currently looking to move to Dumaguete City where my sisters now reside (and where I regularly visit).

TG. Where do you think of as home: Pagadian in Mindanao or Dumaguete in the Island of Negros, Visayas? Or has your army background made you restless – like Jack Reacher in Lee Child’s books – or longing for fixity? My father moved every year in his childhood because his father was a major – in the Salvation Army. I think it left him hungry for a sense of place, an unchanging home.

MV. That’s a very interesting question. In the Philippines, I now think of Dumaguete as home. I moved there when I was 17 and lived there for more than ten years. I am a bit restless, in that I don’t like to be fixed in one place for too long without travelling. But for the places that I consider home (Adelaide, Australia and Dumaguete) I like to have a base, and a space to play around. I used to have a place in Dumaguete but not anymore, and I am wanting to re-establish a studio and place to stay there.

TG. You are obviously close to your three siblings. Are they sisters or brothers? What have they gone on to do?

MV. Two sisters and one brother. Yes, we’re a pretty close family. My two sisters work from home for international companies and my brother is a mountaineer by profession. He lives in Ilo-Ilo so I don’t see him as much, but we try and organise the occasional climb together. My siblings all have their own families and children too.

TG. Do you have children?

MV. I have an 18 year old, Azul, and a 5 year old, Nailig. Azul is currently studying in Melbourne and our little one has just started school.

TG. Is Azul by an earlier relationship? Is he named Azul as in sky? Is Nailig a Gaelic or a Tagalog name?

MV. Yes, Azul is from an earlier relationship. He has lived with us in Australia since he was nine. His full name is actually Lazuli – as in the stone, lapis lazuli. Nailig is a Cebuano word, although it is very old language so not many people know it. The root word is Ilig, which means ripple or flow, therefore Nailig would actually translate as there is a ripple or there is a flow (as na is a shortening of naa, which means “there is”). It is also the name of a lake in the crater of Mt Talinis – a place in Dumaguete that I have regularly climbed since college. Anna and I met in Dumaguete so we decided on a name that had a connection to the place.

TG. What wonderful names! Is Nailig a girl or a boy? Have you and Azul become Australian citizens? This is really a question for later as is also whether having a child has affected your work. Having children certainly changed the way I think about art, life and teaching. I maybe had some effect as both the daughters have become artists!

MV. Nailig is a girl. Yes, we are both Australian citizens but are also allowed to maintain our Filipino citizenship. Yes, definitely kids have impacted my work. It has made me less transient for one thing. I now look for residencies where I can bring the kids because I don’t like to be away from my family for too long. I find being around young kids is great for creativity – they are uncarved blocks when it comes to creativity, they don’t have boundaries and inhibitions yet and so are very present and observant.

TG. My memories of when my four children started school is that you suddenly had more time but that part of their life became unknown to me. That their experience of the playground, class etc was something they could never share with their parents.

MV. That is really true when they start school. You go from knowing every part of their world to having to let go and accept that they have their own lives. When I named Azul, it was because he was like a precious stone to me. But as he grew, I realised that he wasn’t mine in the sense that I owned him. He is his own person, which I really love and admire.

I’d be interested to hear how having children changed your way of thinking too.

TG. I think being in reminded of the importance of play. and the fun of play! The need to explain things clearly – my then teenage daughter was my reader for my Conceptual Art book. If she couldn’t understand what I meant I had to make it clearer. And deeper down there is a sense of continuity: things will carry on after I kick the bucket. Kids are also very good at pricking one’s pomposity.

I think you could also add vis-à-vis children that there was a terrible sense of loss when my first marriage fell apart and my first two children moved over a hundred miles away. I carried on seeing them as much as I could but it was difficult to deal with.

MV. I agreed with everything you said about kids, about play and also continuity. And I love that your daughter helped test out your book in that way. Yes, I felt that loss you speak of when I first moved to Australia and Azul was living with my parents.

TG. Looking at the otherwise very extensive chronology in your book, the only thing listed in the first fifteen years of your life is that at the age of six you started playing chess competitively. Are you an aggressive chess player or a cool, cerebral player? Do you still play? When I look at your works which are almost always multi-part I can see a connection to the chess board with its 32 movable pieces.

MV. I think I can be both types of players… I play blitz sometimes and that is a more aggressive way of playing as you’re also chasing time. Yes, there is definitely that connection with my work. Also, there are endless possibilities with chess, which I think relates to my tendency to keep reconfiguring and repositioning works. There is also a connection between chess and my interest in space and territory and occupation.

TG. I am trying to imagine your early years. In your home were there any books on art? Were either of your parents interested in art? Did you like making things as a kid? models? Lego? etc.

MV. No Tony, no art at home. It was a struggle. But I was always drawing and making things. I was not that privileged in terms of toys when we were kids. But not having too much was probably a good thing because I had to make my own toys. Also, my grandpa was a carpenter so I spent time in his workshop.

No art books at home either, but many about military tactical formations. I didn’t read any art books until I went to university. I was studying accountancy and later on engineering, but I was more interested in art so I started reading whatever was available in the Silliman library.

But as I’ve grown older and reflected on my early years, I have realised there was art in my childhood. There was music, storytelling, performance etc. But there was certainly none of the kind of contemporary art I encountered later on: that I had to actively seek out.

TG. As a kid I was fascinated by military tactics. I once recreated the battle of Waterloo in my bedroom. I loved looking at maps of battles – all the battalions and squadrons and artillery batteries arrayed in formation. And I can see that sort of map – patterns imposed on chaos – echoing in your works too. My dream was to be a general. But as a skinny, slightly autistic kid a career in the army was never likely! Chess of course is a war game – witness the knights and castles. Do you still read books on military matters?

MV. I think we would have been friends as kids! I can clearly memorise military formations up to now. I became a Battalion Commander when I was in senior high school as part of the Citizen Army Training (CAT). It was very competitive because each high school had to participate in a tactical inspection. My dad had all the books because he was a tactical inspector for the university and sometimes in high school. But I don’t read about war or military matters anymore – I somehow dropped it but that history still comes out in my works. I love that description, “patterns imposed on chaos” – there is always a tension in my work between control and subversion, whenever I create a pattern, I then try to subvert it and vice versa.

TG. I was fascinated that in your book you included four photographs of your passing out parade as battalion commander. Should I call you Colonel Valenzuela? It was important to you?

MV. Haha, it would be Cadet Colonel but please don’t call me that! It was important to me because the military shaped my childhood in so many ways. And I almost went further down that path. And then my departure from this path to become an artist represented such a seismic shift in my life.

TG. This happened at university. You went to Silliman University in Damuguete. Was there a fine art department there? I have read in your book’s chronology that you studied accountancy and then engineering but by your second year were more interested in art and according to your chronology painting and drawings. Traditional, representational things I assume. It is indicative that you do not say in your chronology whether you actually graduated. Did you? And in Engineering? How did your parents feel about your change of direction?

MV. Hehe that is a very good pick up – no I did not graduate. My sisters still tease me for spending so many years at university and coming out with nothing, at least not with a piece of paper. I studied management in between accountancy and engineering as well! There was no fine arts course at Siliman, or the other universities in the city, at the time. Yes, I started off with very representational works, most of which now make me cringe. My parents were not happy about my change in direction. It caused a rift for a while but I understand where they were coming from. They worked hard for us and wanted us to have a good future.

TG. When did they come to terms with your errant trajectory in life?

MV. It was some years, but I think they just accepted it in the end because they realized they would never be able to stop me.

TG. The next few years up to 2007 when you have your first one-man show can be described as a very varied apprenticeship. Like many other artists you credit the curator Bobi Valenzuela as an influence or mentor. Were you related to him? What did you learn from him? You did a lot of work organising exhibitions in Dumagaete at this time. Were you considering a career as a curator rather than an artist?

MV. Yes, my early years as an artist were very varied, as I was educating myself and trying to soak up experience and knowledge in every way possible. I’m not related to Bobi, we met when he visited Dumaguete to conduct a workshop for artists. I learned many things from him. His legacy is all about the power of art in the community, and the social relevance of art. These early lessons have stuck with me.

I never really considered a career as a curator. Artists in Dumaguete organised almost all of the exhibitions during that time, as there were no formal art institutions and galleries. I took the lead on a lot of projects because I have always liked gathering people – and I guess I was avoiding my university studies hehe. But this approach to art, which is more collaborative and blurs the lines between artist and curator, is I think a common experience for many artists in the Philippines. As opposed to Australia, where art practices are more individual and projects are often initiated through institutions and formal art structures.

PART THREE: 21st August 2024

TG. You went to Silliman University in Dumaguete which was the first university set up by the Americans. It’s a Protestant university, and saying that, I realise I have not asked an obvious question: “Were your family Catholic or Protestant?”

MV. My family are Catholic.

TG. And have you stayed a Catholic? Do you ever go to church? Or are you, like most Filipino artists a lapsed Catholic who may still pray?

MV. No, I haven’t stayed Catholic. I’d call myself agnostic – I have a sense that there is something greater than me but I don’t subscribe to a particular religion.

TG. Mark, I am fascinated. Dumaguete is not a big town. The census of 2020 found 134,103 people. A town that size in the UK would be most unlikely to

have a serious art scene. What makes Dumaguete special? Is it the Universities? Have any of the other artists you showed with in Dumaguete gone on to establish a career in Contemporary Art?

MV. Yes, the universities play a huge part because there is a large student population. There’s also a big writing community in Dumaguete and their annual writer’s workshop is highly regarded. There have been many contemporary visual artists who have lived or studied in Dumaguete, Paul Pfeiffer, Maria Taniguchi and her mother Kitty Taniguchi, Kristoffer Ardena, to name a few.

TG. Were any of those there at the same time as you?

MV. Paul was before me but I remember him in Dumaguete and then we met later on when he would visit. Maria is my age, but I think she left for uni and I was much closer with her mum, Kitty. I used to hang out at Kitty’s place, Mariyah gallery (one of the few artist-run initiatives at that time) and organise shows. Kris was one or two years older than me and he left the city too, so I met him later on. The people I mentioned are primarily those that left Dumaguete and had international practices. But there were also several really good artists who I worked with at the time, like Babbu Wenceslao, Jutze Pamate, and the late Michael Teves, who stayed in Dumaguete and focussed more on the local art scene.

TG. I think you went up to Manila in 2004 – was it difficult to meet artists there and make ends meet?

MV. I think it was in 2006 that I went to Manila. It was definitely difficult to make ends meet. I actually got stuck in Manila for a while, as many people from the provinces do. Luckily for me it was only two or three months. But it was a very difficult time. I was stubborn and didn’t want to ask for help.

TG. But the next year (2007) you had your first person show in Manila at Duemilla gallery, Warzone. It was (a) mainly of ceramics, but (b) an installation of ceramics and (c) overtly anti-military. Was this a conscious attempt to negotiate your way in that uncertain gap between studio ceramics and contemporary art? Was it also an attempt to exorcise the military aspects of your childhood?

And did you sell anything from that show?

MV. I can’t quite remember. I sold some works, but it wasn’t a sell out as I still have a few. What I remember is that my terracotta installation was sold, but it was split up among several people. As a young artist I wasn’t really in a position to dictate the way my works were sold. But these days I’m pretty clear about selling my works as installations and rarely sell individual ceramic pieces. Sometimes this means works don’t sell, but I’m okay with that.

Warzone, 2007

Warzone, 2007

Warzone, detail, 2007

Warzone, detail, 2007

The show had one installation of terracotta works, but also had a series of mixed media works. The mixed media works also referenced conflict and the military, with images of conflict made up of children’s toys: toy soldiers, transformers. So yes, exorcising the military and the conflict from my childhood is the perfect way to phrase it. At the same time, it was also a broader exploration of conflict and ideas around conformity and resistance.

Untitled, from Warzone 2007

Untitled, from Warzone 2007

I never really saw myself as a studio ceramic artist; I began using clay because it was a readily available material. Artists in Negros tend to use terracotta because it is a backyard material and not because they have chosen ceramics as a discipline. Many artists work across a few materials, of which terracotta is one. But once I started working with clay, I became a bit obsessed with it and its never-ending possibilities. However, I was never drawn to becoming a studio ceramic artist. I have always been interested in how this material can work with other materials, and how I can use it for installation, and how it relates to the concepts I want to explore.

TG. Was this a very isolated position to be in the Philippines of 2007? I can’t think of anyone using ceramics in such a non-craft way. I do recall some years ago you saying to me that you wished ceramicists in the Philippines were more open to innovation elsewhere – that, for instance, that they would look at the very hybrid work of Grayson Perry.

MV. There were a few artists at the time using ceramics in their contemporary art practices – Joe Geraldo, Charlie Co, Kitty Taniguchi, Julie Lluch, to name a few. My observation during those times is that many artists were using ceramics for sculptural practices. I was always interested in space and formations, so I never really looked at my clay works as individual objects or sculptures. For example, I had a work in 2005 that combined a series of terracotta sculptures with hundreds of plastic toy soldiers. I think some of the artists I mentioned were experimenting with groupings, so I don’t think it was an isolated position. But I couldn’t say if their intention was the same as mine. I was always most interested in space and how to fill a space. I think this is why I have also always liked organising and designing exhibitions.

TG. Were you looking at installation artists such as Kabakov, Boltanski or Anne Hamilton? Obviously, you would only know of them by magazine or book and, by 2007, internet.

MV. I wasn’t familiar with those artists at the time. My knowledge was very locally focussed, plus whatever I could read, which was often art history as opposed to what was happening currently.

TG. Coming from the UK I was used to artists being openly influenced by overseas artists: de Kooning, Stella, Guston, Baselitz, Gerhard Richter, etc. It remains a surprise to me how rarely Filipino artists refer to contemporary artists overseas. The exceptions are Chabet’s students. He made a point of making them acquainted with artists that might interest them – for instance he leant a book on Rauschenberg to Geraldine, a book on Jannis Kounellis to Poklong Anading. I don’t think this is just about lack of access to overseas art. Nor some petty chauvinism. I think this is a “we must show we can do this on our own” attitude. Am I right?

MV. That’s really interesting. It was a bit of both I think. There was a genuine lack of access for me. I wasn’t able to study fine arts so I didn’t really have anyone giving me books on international artists or pointing me in those directions. Although, when I met Bobi he introduced me to John Berger’s writings. I was always interested in what was happening outside of the Philippines and I would try and educate myself by going to the library, but as I mentioned, most of the books at that time were historical rather than contemporary. But yes, there was at the same time a sentiment that we wanted to make our own art and not get co-opted by the West. I really admired artists like Santi Bose, Roberto Villanueva, and Tence Ruiz, who were internationally engaged but also making art rooted in their experiences as Filipinos.

TG. And since you moved to Australia where there is much greater access to global art do you find your attitudes changing? Did you get interested in people like Perry and Edmund de Waal?

MV. In the years between my very early self-education in art and moving to Australia, I had managed to build my knowledge of contemporary international art. Increasing access to the internet and my experiences in Manila helped with that. And then moving to Australia certainly added another layer to my knowledge and experiences. I like Perry because he does many things, from ceramics, to textiles, to performance. In terms of ceramic artists, I also like the works of Peter Voulkos because of his skill and experimental attitude, and Viola Frey because of her colourful larger than life sculptures. I’m drawn to artists who push the boundaries of ceramics. Beatrice Wood was another one in her time.

TG. The 2007 exhibition could also have been aligned with social realism, something I believe Bobi Valenzuela had promoted. How was your attitude to Social Realism at that point? Obviously, you were feeling anti-military at this point, but were you politically active in any way?

MV. I was definitely aware of and influenced by the social realist movement. I had a great respect for those artists and for Bobi of course. I think my direction at that time was different to that of the social realists, but there were definitely points of connection and intersection. Yes, I was politically active for a time but I’ve always felt more comfortable questioning and critiquing through my work, as opposed to more explicit forms of activism.

TG. Was the most important consequence of the 2007 show at Duemilla that you got into the Ateneo art awards for 2008? That has often functioned as a gateway to a career in art jn the Philippines. Annoyingly, I have all the Ateneo award catalogues but only from 2009 onwards! What other artists were in it? Who won the actual awards?

MV. Having a solo show in Manila was a big deal for me. I felt like it was a make-or-break moment. And then getting nominated for Ateneo was very important to me as an emerging artist. I think the artist that won was Poklong Anading.[1]

TG. In 2009 you showed again at Duemilla with a show called Platoon of Strangers. Are there any images of that show? If not could you give me an idea what it was like: was it an extension of Warzone in 2007 or a new direction?

MV. Yes, it was an extension of Warzone. As with Warzone, the works featured covered faces, conflict imagery, and military formations. I was continuing to explore ideas around conformity and resistance. There was a sense of distrust that ran through the show, with featureless or covered faces – it was kind of about not knowing who your enemy might be. It wasn’t my favourite show… it was a bit weak. But it was an attempt to merge the two different disciplines I was working in at the time, painting and ceramics. It was important in that sense. I recall I had a big painting of a figure with a gun and I positioned it in such a way that he was aiming at a formation of ceramic figures on the other side of the room. And then there was a much smaller painting with a figure aiming his gun at the big painting. This kind of play between different works (and different mediums) was the start of something for me… the act of creating narratives and relationships between works within an installation.

TG. Paintings! Not something you have persisted with, I believe. But this play of eyes – this drama rather – is interesting. You were using art works a bit like actors on a stage – or dancers. Were you involved in the theatre in any way during your Dumuegete years?

MV. I still paint but I only occasionally include paintings in my installations. And I think of many of my ceramic works as paintings and drawings also. I was never part of the theatre, but I occasionally helped to paint the sets or backdrops for Silliman University productions, West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof. Interesting your phrasing about eyes and actors, because I do kind of think of my works as being alive. Part of why I am constantly reconfiguring my installations and moving things around is because it reanimates the works (meaning it’s alive again as opposed to being stale or dead in one spot) and also it makes the space somehow alive as well.

TG. I would be interested to see how you “curate” the objects in your house. I rather assume you do.

In 2011 you shifted gallery to Artinformal who have represented you ever since. Your first show with them in 2011 was entitled Zugwang which in German means a compulsion to move, when your opponent has put you in a position where all your potential moves are bad.

Was the show the breakout show, that as you have intimated, Platoon of Strangers was not?

MV. Yeah, I do love placing and arranging works and objects in my house. But I do this more often in my own studio. I like the idea of a studio as a work in progress itself rather than just a working space for projects and exhibitions. In this way I can constantly play around with my old works.

I think Zugzwang was pretty successful as far as commercial gallery shows go.

Domino Effect, in Zugwang 2011

Domino Effect, in Zugwang 2011

Domino Effect, detail, 2011

Domino Effect, detail, 2011

One of the works in Zugzwang was called Domino Effect and consisted of about fifty terracotta ears, each encased in a rectangular glass box and installed in a line like dominoes. Other terracotta works were installed on crates and slabs of wood. In this show I started to combine ceramics with other materials (as I did in my last show at Duemila in the same year) and try to move away from putting ceramics on plinths… the fixings/platforms etc with which I install ceramics have become more and more important parts of the works themselves over the years.

TG. I do like this way of discussing art works of which there are no illustrations. It’s a new experience for me! Just like discussions about classical Greek paintings of which all are lost but we have verbal descriptions of them.

MV. Haha, I’m sure I can dig up some photos for you if you would like them. They won’t be great quality though!

TG. Well, like any good dramatist you have to begin with the stage! has this instinct to make complex multi-part works made it difficult for Tina at Artinformal and other dealers to sell your work?

MV. Yes, I’m sure I have made it tough for Tina and others. Artinformal has always afforded me a lot of freedom with my works though, which I have appreciated. But many commercial galleries/opportunities aren’t looking for installations, which is understandable. I have moved away from this direction a little because I don’t think my work is a great fit. I’ve had a few opportunities in recent years to make large works outside of the commercial gallery space, which has been really great. It has allowed me to push my practice and work at a different scale.

Going back to Zugwang, yes, the compulsion to move… the show was all about being stuck or controlled, having limited options or pathways open to you, and whether there is potential for resistance when in that position. It was about individuals in the face of oppressive power, I guess.

TG. Alas, I can’t find my copy of the 2012 Ateneo Art awards in which you also appeared – so much for my librarian skills! Perhaps more importantly that year you had a one person show in Australia. Was it serious a culture shock working in Australia?

MV. Yes it was, even up to now Tony… or probably forever… I was already 30+ when I migrated to Australia. And it’s always easier to move to a different country when you are a lot younger, it’s easier to adapt. But the beauty is it offers you a different perspective too.

TG. In that year (2012) you also had a show at Artinformal in Manila. Did you make different sorts of works for the Philippines than Australia? If so what? I guess I am asking if you started becoming a different artist, a different person even, in Australia. And, yes, I myself am conscious of working differently in the Philippines than I did in the UK. However, also I am now intensely aware of being English.

MV. Yes, they were quite different shows. Entry was my first exhibition in Australia and consisted of ceramic works I had fired in a wood kiln that my partner and I had built (this was an experiment – my one and only solo show of woodfired works). It was about my experience of this new place, but mostly about looking back and reconsidering my decisions. It is exactly as you said of your experience, I became intensely aware of being Filipino and felt that I saw the Philippines with new eyes, now at a distance. My show in the Philippines in the same year was a series of drawings, mainly because it was easier to transport them to Manila from my new base in Australia. The drawings depicted a series of floating balloon-like body parts – I think I was feeling quite fragmented at that time, from the migration. Moving to Australia has changed both me and my practice in some ways, but I’ve also resisted the adaptation or assimilation process a fair bit. It has made it harder for me in some ways but I needed to retain my sense of self. I still go to the Philippines for a few months every year and that has kept the balance.

PART FOUR: 24th August 2024

TG. Since moving to Adelaide in 2011 you have tried to maintain a sort of umbilical cord to the Philippines by various means: firstly, an ongoing working relationship with my neighbour, ceramicist Pablo Capati, secondly, an organisation run by you and your partner Anna, Boxplot. Is Boxplot still active?

MV. Yes, I have definitely tried to keep my connection to the Philippines. I spend at least three months of every year there for a start.

My friendship with Pablo has also been important. Working with Pablo is always an experience. He is like a brother to me and has always been very supportive. I like his idea too of helping the next generation of ceramic practitioners. And of course, the occasional wood firing which I really love. We’ve been doing it for some time now, gathering and firing the kiln (we’ve been functioning as a collective for a while and it was just recently that we officially called it watchfire collective). I really love the collaborative aspect of wood firing.

Yes, Boxplot definitely came out of my need to maintain a connection with friends and artists in the Philippines. And we wanted to maintain and promote that collaborative way of working that is so strong in the Philippines. Boxplot kind of came to a natural end with the birth of my second child and then Covid. But we are going to relaunch it under a new name soon (Aliwarus Exchange), as we are still interested in doing the kinds of projects we did under Boxplot.

TG. How many projects did you do under Boxplot? Did you get some public funding for it? Which was your favourite or the most successful?

MV. A quick glance at our Boxplot resume tells me we did over 15 exhibitions, plus other projects and residencies. We did almost all of them without funding – it is difficult to obtain grants here for international artists, they mostly go to Australians. So usually, we would support the Australian artists to apply for individual grants and then figure out the rest somehow. My favourite project was Tambay for the Australian Ceramics Triennial in Hobart in 2019 – and we actually had some support for this project. Babbu Wenceslao, Pablo Capati and I undertook a three-week residency at the University of Tasmania to make our works, leading to an installation and performance for the duration of the Triennial. But I enjoyed all the projects we did for Boxplot, in Adelaide, Singapore and the Philippines. We also got to travel to Yogyakarta as part of a curatorial collective, which was cool.

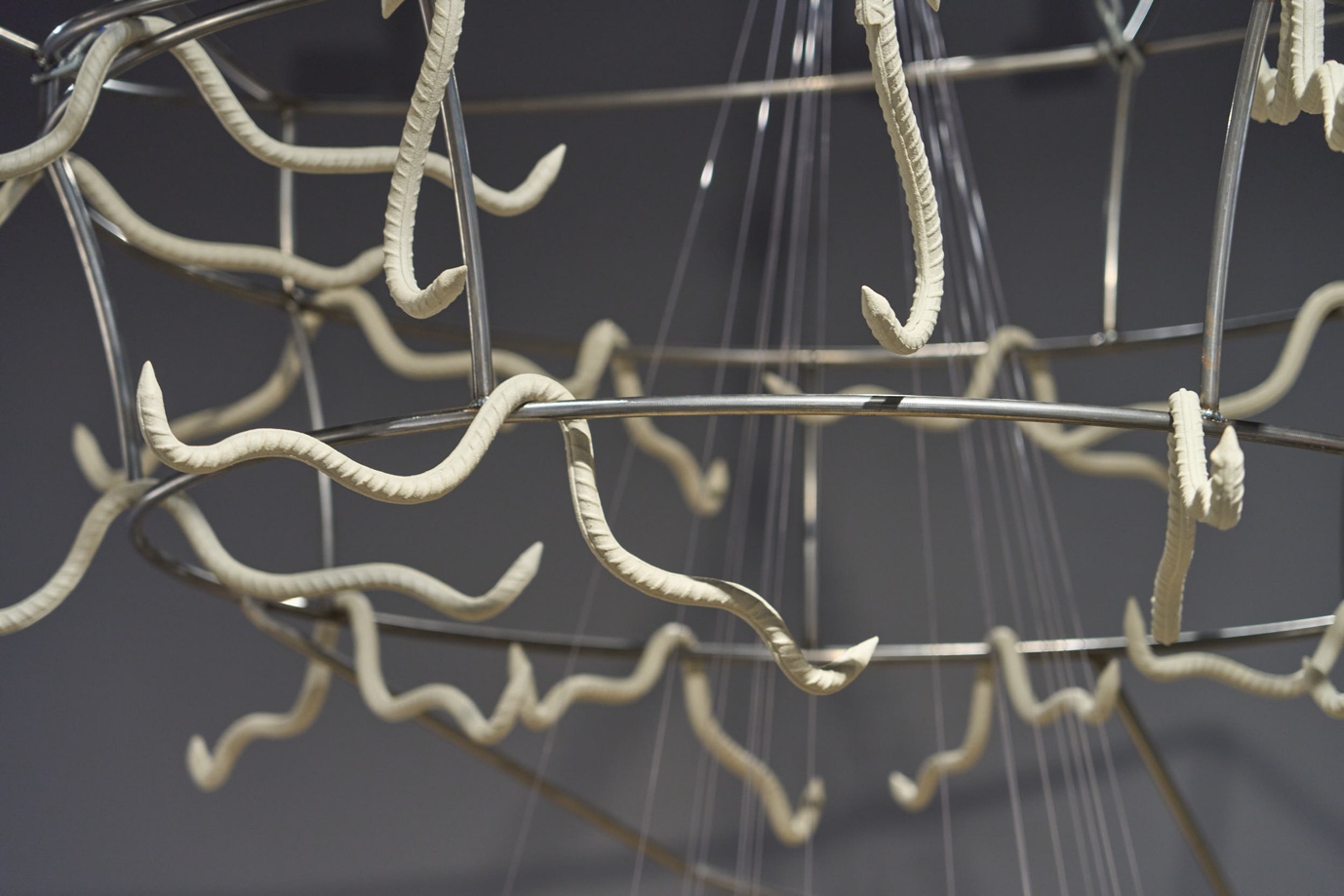

Tambay, 2019

Tambay, 2019

Tambay, detail, 2019

Tambay, detail, 2019

TG. It is tough doing collaborative type projects with no finance but it does mean you have freedom! You don’t have to fill in loadsa forms or make awkward compromises. I have never sought any funding for arttalksea.com because I wanted that freedom – and who in Philippines would fund something like that anyway! But I think at some point a bigger organisation should take it over and commission more interviews than I am capable of doing. There is a big lack of the sort of archival-level interviews that are done in US and I guess Australia. Also, I am sure another person would have far better computer skills than I!

MV. That’s so true. We would often say to each other “let’s just do it ourselves!” because we wanted that freedom and we didn’t want our projects to be dependent upon financial support. And I love the DIY approach as well. We will probably focus on this when we re-launch because there is so much freedom when doing it yourself. Also the grants here require you to have everything planned out well ahead of time, which is not how artists and projects usually work in the Philippines. So the grant system just wasn’t a great fit for what we were trying to do, it can take away that spontaneity.

I think it’s fantastic that you are creating that archive. It is such a valuable resource. A huge amount of work, I’m sure.

TG. I helped run an interview magazine with 35mm slides attached back in the late Seventies. But getting it printed was too expensive and after the break-up of my first marriage I was not in a good place so we only managed five issues. The internet allows you to do things differently – the only worry is that everything can get wiped off so easily. I hope someone somewhere is printing off the interviews on paper and storing them!

What does Aliwarus mean? Will you be doing different things than in Boxplot?

And why is your new collaboration with Pablo called “watchfire”? For some reason the great Jimi Hendrix song All along the Watchtower is now screaming in my head! Will it be doing something different from what you and he have done before?

MV. Yes, I hope so too!

Aliwarus is a very old Cebuano word that means rowdy or restless. My grandfather used to call me “aliwarus” when I was being pesky. But I have kind of taken the word and applied my own meaning to it, as like an interruption or subversion. Rough and rowdy like the 2020 album of Bob Dylan, who was the one who wrote All along the watchtower… but the same with me, it’s Jimi Hendrix’s version that sticks.

I think Aliwarus Exchange will focus more on DIY projects and residencies, and less on exhibitions in formal gallery spaces. The activities we do could be anything from experimental sound nights, to film screenings, to zines, to street art. It will be spontaneous and informal and make use of my studio here.

Watchfire is the name we have given to the collaborative projects and works of the ceramic artists we regularly work with. It is a collective that has been going for many years, but the boundaries and membership is pretty fluid and ever changing – and we have only recently given it this name. We took the name from an exhibition we organised at Silverlens in 2019, another Boxplot project, that included Jon and Tessy Pettyjohn, Alvin Tan Teck Heng, Shozo Michikawa, Joey de Castro, and Pablo Capati. Once again, this exhibition considered the collaborative act of woodfiring, quite literally the need to watch the fire in shifts.

TG. I am looking at images in your book of New Folk Heroes. There are eleven separate elements – most of which are multi part. Dominating are three figures that look like wobbly dolls with Batman type masks, Around them are several shapes that are like ducks or muscles with human fingers for heads. It seems to be sort of a transformation scene. On the walls a collection of coat hangers melt – and there are neat drawings of ducks and hands and feet – and a hood in which the face has transformed into spaghetti or thin rolls of clay. Did this begin with a narrative or did you just improvise the pieces as they were made one by one? Folk heroes? Folk stories? Often your works look like folk or children’s stories that have taken form in a different way. Are you a fan of the Brothers Grimm or Angela Carter’s reworkings of their stories?

MV. In the Philippines, we’ve always had these folk heroes who were brave fighters as part of the resistance etc. And then later, because the justice system has always been so inadequate, we’ve had vigilante type figures who adopted that folk hero status. I made this work in the context of the Duterte death squads and the rise of violence in the war on drugs. In this context, there were so called “vigilantes” who were actually operating on behalf of powerful forces. So the concept of “New” folk heroes is meant to be paradoxical and undermine the kind of hero status of the vigilante. If that makes sense? But yes, I do often incorporate imagery from my childhood but it’s probably more drawn from the comics I was obsessed with than the Brothers Grimm. I’m not familiar with Angela Carter, I will look that up. The morphing of animals and body parts and hybrid creatures also draws on animism and the folklore I heard as a kid.

TG. You should try Angela Carter. The Bloody Chamber, Vintage, 1995. Feminist re-writings of folk stories. Well-written.

Did you hear folklore from your parents or other children? Were they stories very specific to Mindanao. Yes, in 2016 with the early years of Duterte’s presidency one would have picked up the reference to vigilantism and the “War on Drugs” quickly. Did people do so in Adelaide though?

MV. It needed more explanation in Adelaide, which is why I was really glad for the opportunity to reconfigure the work for Art Fair Philippines the following year.

Yes, I heard a lot of stories growing up from my parents and elder neighbours. In Pagadian, we lived in a very tight knit community with lots of distant relatives. All the kids used to gather around to hear the stories. There was also lots of playing music, which is how I learnt to strum the guitar and even playing chess and dama (Cebuano form of draughts).

TG. How did you do the “explaining”? By a wall text or just talking to people?! How did you change it both for the Philippines, and for an art fair context?

MV. Mainly just talking to people. There was a beautiful essay written on the show (a group show) by Cath Kenneally which touched on it in an indirect way. The main difference was that at AFP I responded to the space – the concrete rough environment of the car park.

New Folk Heroes, 2017 in Art Fair Philippines

New Folk Heroes, 2017 in Art Fair Philippines

New Folk Heroes in Adelaide 2017

New Folk Heroes in Adelaide 2017

TG. More brutal and more painful than in Adelaide. I remember that now.

You have said that increasingly your interest is in public projects. What is your most recent public project?

MV. Haha yes I love that description!

I’m interested in opportunities to show in alternative spaces and contemporary art spaces, rather than commercial galleries. It’s not that I am opposed to the commercial scene, I think it is essential. It is just that the works I want to make are no longer a great fit for galleries that require sales and have a quick exhibition turn around. I like to spend three to four weeks just installing, which can be longer than the length of an exhibition in a commercial gallery, ha ha. But these opportunities don’t come up all the time, which is why I also like making works for the street and doing random projects and collaborations.

TG. We should talk about Still Tied to a Tree.

MV. It would be cool to talk about Still Tied to a Tree, because it was the exhibition that I made to coincide with the book launching. Therefore it wasn’t included in the book and hasn’t been written about.

PART FIVE: 16th October 2024

TG. Mark, many apologies for the delay in getting back to you. I had hoped to write some questions for you on the flight back to UK but, perhaps inevitably, it was impossible to work cramped up in a plane. I could read, yes, but not write. And then on my return it took some while to get back in the mood of writing. It took me a week to write the thousand words of my last Tuesday in the Tropics. Do you manage to work every day or do you have days where nothing will work?

MV. I work every day but there is not always a tangible output. Some days are for thinking and not making. But yes of course, I do have days when nothing works. At that point I step back and give my work space and channel my energy into something else. I roast beans and brew coffee, I play chess, listen to or play music, spend time in the garden.

Mark Valenzuela. Still Tied to a Tree, 2024

Mark Valenzuela. Still Tied to a Tree, 2024

The following 8 images are details of the same work

TG. There was once (1976) an exhibition in the UK curated by R.B.Kitaj entitled The Human Clay. Looking through the many images you sent me of Still Tied to a Tree that came to mind, even though Kitaj’s exhibition, a call for a return to life drawing, and the necessity of art to be based on the human figure, may not one have been one you would have wanted to show in. Basically, in your installation, things made with clay are animate, possibly human, but things made with wood, metal and rubber are the environment, or prison, they live or are contained in. I guess that is true of all your work: clay stands for flesh. In the Old Testament there are several references to God as like a potter making men from clay (see Job 33:6 or Isaiah 64:8 or Jeremiah 18:6) And as Job so cheerfully reminds us clay easily crumbles to dust:[1]

Remember, I beseech thee, that thou hast made me as the clay, and wilt thou bring me into dust again? (Job 10: 9 King James Bible)

MV. What a beautiful observation. That is very true that the clay elements of my work are the embodiment of flesh or life, they are the animated objects that are held by (and often resisting) the fixed structures. I also used steel and timber elements to create a space for the ceramic works to occupy, similar to what a canvas does for paint and paper for drawings, it is somehow like a stage for my works.

Your religious references are interesting and I’m familiar with the story of golem. Philippine belief systems also speak of humans being made from clay. I’m not quite sure if this is the Christian influence or if it predates that.

TG. Mark, yours is a very Foucauldian vision. That is to say one very much in tune with the emphasis Michael Foucault places on the role of order, taxonomy and disciplines in controlling not only our work, but how we live. Have you ever read Foucault, especially The Order of Things or Discipline and Punish?

MV. I’ve read a little Foucault – I didn’t finish the texts you mention. I must go back to it with this observation in mind. It is true that I am preoccupied with the systems that control us.

TG. Is the discontinuity of experience between the Philippines and Australia a problem for you, or does it inspire you? For instance, in Still Tied to a Tree there is an image very familiar to me the simple tent-like huts I see in many fields and gardens of the barangay where I live – basically two planks propped up – the shelters that fighting cocks are tethered. But very few viewers in Australia would have had that association.

MV. I’m comfortable with the discontinuity of experience. My work always has several layers and having these two worlds now allows me to layer these perspectives and experiences. The works you mention reference both the shelters for fighting cocks in the Philippines as well as the picket fences you see here in Australia, both of which speak to ideas of being tethered or contained by boundaries. I’m aware that audiences won’t always understand every reference, but I also think it is important to present audiences with unfamiliar imagery and ideas.

TG. In terms of understanding, how much written explanation did you or the curators put up on the walls for Still Tied to a Tree? Often curators want to put up more written information than the artist.

MV. In fact, there was no written text at all for that exhibition. It was the show that corresponded with the launch of my monograph, so I think the focus was on the book in terms of writing about my work. But actually, it worked really well for this show not to have any written text because either the curator, Andrew Purvis, and/or I was always present during the exhibition. So we were able to talk to audiences about the work, which was great. I set up a little chess set in the space and made puzzles for visitors. I also like to play with my work and reconfigure it, so visitors would often find me in the space moving my works around like chess pieces.

TG. Are you secretly a performance artist?

MV. Haha! Perhaps. There are often performance elements to my works, whether I am moving things around or brewing coffee or playing chess. I like to interact with the work and with audiences, so being present in the space helps me do that. I suppose that could be considered performance, although it is not really planned most of the time.

TG. I am fascinated by issues of interpretation or understanding or association with a complex work like Still Tied to a Tree. Can I just give some responses to some of the elements?

MV. Sure!

TG. OK Mark, here are some responses to six images if Still Tied to a Tree. Do you want to respond to my responses?

Your work often asks to be seen anthropomorphically, or metaphorically. A black man hanging on a gibbet. Some skittles in the background.

MV. This work is perhaps another one that requires some explanation for non-Filipino audiences. The hanging objects are ceramic banana hearts, which reference a story that I was told as a kid. The story is based on ancient indigenous beliefs that the banana heart will drop a pearl (mutya) at a certain time, and anyone who is able to consume the mutya will become invincible and even immortal. However, one is very vulnerable in that moment when the mutya drops as that is when other creatures and monsters also appear to vie for its power. In this work, I reconfigured the story and introduced the steel elements to speak of more contemporary power struggles and structures of control. Anyway, that was a bit of a tangent but reinforces what you say about my tendency towards the metaphorical and anthropomorphic. The creatures surrounding the banana hearts certainly have an anthropomorphic quality as object-beings.

TG. Worms or coat hangers. As always, a contrast between the organic and the inorganic.

MV. Butcher’s hooks / coat hangers. But I love that they could also be seen as worms.

TG. I always like the vagaries of the alphabet. On my book shelves your book sits between Meyer Vaisman and Remedios Varo. Exiles or ex-pats all three. You are a sort of opposite to Vaisman the appropriation artist and maybe in ways akin to Varo, a late surrealist, her works filled with a delicacy of touch, mysteriousness and constant longing. But her work, despite her exile from Franco’s Spain, lacks the menace that often lurks in your work.

Ears growing on trees is definitely a surrealist image. But a pile of ears is more like something from Goya – some war atrocity.

Drawing on clay tablets is only a step aways from painting tiles. A massive tradition, especially in Holland and Portugal, but one normally seen as decorative. Have you ever tempted to tile?

MV. I like that you see menace in my work. The work with the ears was an old work reconfigured for this show. I made it in response to the massacre of journalists in Maguindanao – so yes, an atrocity of civil conflict. I haven’t explored tiling yet. If I did, I would want to find a way to move away from the idea of surface decoration. When I draw on ceramics, the drawings are related to form – so that when they fuse in the firing process they become a single cohesive work – as opposed to a decoration on a surface. The drawings in this image are actually works on paper – I still draw almost every day and this was a body of work that I made alongside the ceramic elements.

TG. Is this yellow-black tape called hazard tape? The vase (?) on the left with the two breasts (?) reminds me of Minoan or early Greek ceramics of women (maybe priestesses with snakes). Are you interested in such early ceramics?

MV. Yes, it’s hazard tape. I often use it in my installations to denote boundaries and borders.

I’m definitely interested in early ceramics. I like the freedom of form in the early sculptural ceramics. I read a lot about ceramic history, and then try not to be bound by it. There are a lot of rules in ceramics that come with such a rich history. I like to know these rules… and then find ways to break them.

TG. A vessel with a moustache next to a fallen vessel. But your vessels never quite look human. A bit human-like: they might trigger some sort of recognition, but probably not empathy. Do you want us to show empathy? Or make us feel estranged and curious: e.g. “What sort of thing are we looking at?”

MV. That is an interesting observation. I have a love for each work I make, but not empathy exactly – and I’m not surprised that they don’t trigger empathy in others. It may be because I often make works that reference human flaws or things that I want to challenge – my works are often monsters or creatures that reference people’s tendencies towards violence, control, domination etc. Often my works will have these very strong masculine elements – moustaches, testicles etc – which is a critique of machismo and the violence that goes along with it.

TG. Was this the view from the entrance? Or a view looking at the entrance? Lifted high the “worms” or butcher’s hooks look more like squiggly drawings of birds in flight.

MV. This view is towards the entrance. I like that this work has a beauty from a distance. Up close, you can see that the steel structure is in the shape of a police hat and the “worms” are hooks. So I like the idea of violence and control concealing (or projecting) itself as something beautiful.

TG. Thanks for all those responses to responses. It really is a complex work!

When we started this interview, you were making a piece for a performance by Gabber Modus Operandi re-using elements of Still tied to a tree. Was Still Tied to a Tree a work or a collection of works? Was it conceived as a whole in advance or brought together more expediently for the show? Were separate elements for sale?

I am minded that Christian Boltanski always remade his works for exhibitions. Collectors who lent works they owned were often perturbed when an installation they owned was returned with five light fittings instead of seven or nine light fittings but of a different make.

MV. Yes, I reused some elements from Still Tied to a Tree for a recent work. Speaking of performance, it actually ended up being a separate performance itself. My work was combined with a sound element, which I collaborated on with Aly Bennett, and a light projection by Miles Dunne. A group of us (Aly Bennett, Yan Cinco, and Tating Destros) then performed with the work (Gabber Modus Operandi were later on in the line-up for the night).

Still Tied to a Tree was conceived of as a whole installation. It was almost entirely made up of new works. There were two or three ceramic works that had been in previous shows, reconfigured for this show… or making a cameo :). There were some separate elements for sale. It really depends on whether I can see a work as being able to stand alone or not.

I love that about Christian Boltanski. Artists that work in installation are often confronted by the fact that after an exhibition, the works need to be stored or kept somewhere and they become dead. So I love the approach of reconfiguring and reusing a work as it keeps it alive. It is more sustainable also.

Regarding selling, when I sell my works or a grouping of works they always need to be reconfigured anyway, as they need to be adapted for the space they are in.

TG. After showing Still Tied to a Tree in Adelaide you showed it in Manila at Artinformal. How did you change it for there?

MV. The Manila manifestation of Still Tied to a Tree included an installation of the ceramic butcher’s hooks. The show in AI (Artinformal) was much smaller, really to launch the monograph. All I could bring over at that time were the butcher’s hooks. I also showed the series of drawings from Still Tied to a Tree and some old works (the trigger fingers) from New Folk Heroes.

TG. So it is a bit like when opera or theatre companies go on tour with a smaller cast and limited scenery, improvising as they go.

MV. Haha! Yes exactly, and making sets from what they can scrounge.

TG. Apart from transport issues – i.e. what was feasible to bring over – AI is a commercial gallery. I presume you sell more work in the Philippines than Australia, Although the public sector support for art here is weak the collecting base is I suspect wider here than Australia.

MV. Yes, I have a stronger collector base in the Philippines. And the thing I like about Filipino collectors is that they are more open to buying ceramic installations.

TG. It was a surprise to me when I moved here to see how adventurous some collectors are here.

There were a lot of elements in Still Tied to a Tree. How long did it take to create them all? a year or more?

MV. Still Tied to a Tree took a year. But I was entirely focussed on the show during that time and not doing much else.

TG. Since showing Still Tied to a Tree are you working on another major project?

MV. I’m working on a solo show for next year at Adelaide Contemporary Experimental (ACE). I received the Porter Street Commission for 2025, which is funding from ACE to develop a major new work.

I’m also currently hosting two artists from the Philippines. They are undertaking a five-week residency here in Kaurna Country/Adelaide, staying with us and working in my studio. This is part of the project I have with my partner, Aliwarus Exchange.

TG. Will your show at ACE be a selection of works including the new major work they have commissioned or something with a greater coherence? eg an installation. Do you have a title for it? Is something bugging you or interesting you at this time that is affecting how you conceive the show. (I must admit at this moment I am totally focussed on Trump and the US election.) How do you begin thinking out a show? by spending time in the space you will show in? Sketching? Reading? Walking about and thinking?

MV. The show at ACE will be an installation. The installation will be one major work made of many components.

The word commission is perhaps a bit confusing, as ACE don’t actually acquire the work. Rather, they provide funding for the artist to develop new work (or a body of work) for the exhibition. I wrote a proposal for the commission opportunity, but I kept it a little loose as I am inclined to keep changing things as I go along. I don’t have a title yet, but it will be broadly focussed on defensive and offensive mechanisms or strategies within a space. Here is a short excerpt from my proposal describing a portion of the work:

I intend to install a crumbling concrete wall from which will protrude white ceramic rebars. I have used these ceramic rebars in previous works as a way of playing with ideas of fragility and strength, and more specifically, to undermine the strength of certain structures – walls, boundaries, things that claim and defend space – by conveying an underlying fragility. In this case fragility will speak to the sense of insecurity that is at the heart of the impulse to defend. Along the top of the wall will be broken shards of ceramics – a defence mechanism usually made of glass that is common in the Philippines when people want to protect their space from intruders. It is symbolic of the economic inequalities in my home country (although the truly wealthy have no need for glass shards – their gated communities are protected by armed guards). I will combine these shards with the type of spikes used in Australia to deter pigeons. Facing the wall will be a steel structure covered in ceramic sculptures. Each sculpture will have a speaker inside it to create a wall of sound. The ‘concrete’ wall and ceramic rebars will vibrate, as if from the sound, again exploring the fragility of these structures.

Anyway, that is part of what I proposed, but knowing myself it will probably shift a bit before the show.

Now as always, I start developing a show with a long period of thinking. Yes, I definitely spend time in the space if I can. For the ACE show, the primary reason why I applied is that I am so familiar with the space. I have visited it often since I arrived in Adelaide and would imagine how my works might occupy this beautiful space.

TG. Have you completed any of the components you mentioned yet?

MV. Nothing is complete… but I have made some of the ceramic elements – some rebars, and also some works inspired by the three cornered jack (considered a weed in this country), which will be another element of the show.

Mark Valenzuela. “Three cornered jacks” 2024

Mark Valenzuela. “Three cornered jacks” 2024

TG. When will you next show in the Philippines?

MV. I’m not sure when I will be showing next in the Philippines. But I’m going home for two months in November, and I’m thinking of making a project while in Dumaguete. I’ve been talking to some artists there about some ideas for the street, using ceramics. We will see!

TG. I look forward to seeing that. Thanks for your time, Mark

-

Winners were Poklang Anading, Marina Cruz & Kawayan de Guia. Other artists shortlisted were Christina Dy, Lyra Garcellano, Robert Langenegger, Rachel Rillo, Mark Salvatus, Mac Valdezco & Mark Valenzuela. ↑

MARK VALENZUELA INTERVIEWED BY TONY GODFREY

By email

PART ONE: 11-14.8.24

TG. Hi Mark, it was good seeing you last month by Pablo Capati’s kiln in Batangas. Of course, I was not there when the kiln was emptied. What did you put in to fire? How did it come out?

MV. In response to your question, it was a great firing. We fired the kiln for sixty hours at least, taking shifts. I didn’t place too many of my own works in the kiln. I ended up drawing in underglaze pencil on clay forms made by some of the other artists. Anagama firings are always collaborative acts, and so I used the making process to extend the artistic collaboration rather than making my own individual works. I was also interested in the effects of anagama wood-firing on the underglaze pencil. I thought the drawings and markings might disappear when subjected to such a high temperature and long firing, because the underglaze pencils usually tolerate a lower temperature. However, it came out really well. I might consider doing this again in my own practice.

TG. Do you have any images of those collaborative pieces your fired? It would be great to see some? Did you or Pablo take photos?

Before the firing

The final work after the anagama firing where other works from other artists got stuck on MV’s work. Some underglaze pencil lines turned blue instead of just black due to very high temperature and reduction. The collaborative work with Alvin Tan Tech Heng (thrown body) plus Paolo Lozano and Ella Mendoza’s cups that got stuck after firing.

After the firing. A collaboration by Pablo Capati and MV

A small blue jar by Pablo Capati with MV drawings on it. The photo was taken in MV’s studio installed with his other ceramic works with underglaze pencil

In talking about your work there are two issues to deal with. Firstly, that your installations often use many different elements and to illustrate them properly takes many photos! In your recent monograph one multi-part piece Once Bitten, Twice Shy gets 13 separate images! Secondly, that monograph deals with your work from 2015-2022 in some detail so I am going to suggest we deal with maybe just three works from that period: New Folk Heroes, 2017, Tambay, 2019 and Still tied to a tree 2022 and put more emphasis on your early work and your work of the last two years, Are you OK with that?

Or, to put it another way, the book illustrates almost nothing you made before 2013. It concentrates on your Australian years. But looking at the chronology in that book you seem to have been very busy in those early years! By 2012 you had had six one person show and been in at least 22 group exhibitions. I am sure there were some things worth talking about in them.

MV. Sure, I’m happy to focus on works not covered by the monograph, before 2015 and after 2022. Part of the reason the book has so many images of more recent works is that my early exhibitions weren’t well documented and we didn’t have many printable images. My partner Anna’s essay talks a little about my first solo show, but you will notice that the images have been printed quite small to retain the resolution.

However, I think the years you suggest (pre-2015 and post 2022) would be interesting because in the early years I was just starting to experiment with installation-based practice, but the various disciplines I was working in (painting, drawing, sculpture) were not very integrated. Over the years, I have increasingly integrated the materials I work with and become more ambitious in my approach to space and installation. So, there is quite a contrast there. Also, the early years remain interesting to me because that is when I was sourcing my own clay and making use of the local resources in Dumaguete. This period really established my love and understanding of ceramics. Anyway, I may be getting ahead of myself. I would be happy to talk about any of my early works/exhibitions – probably my solo shows are more interesting, because group exhibitions during that period tended to treat my works as individual objects (which even then, I was trying to move away from).

TG. It’s great that you agree! But before we delve into your ancient history can we firmly place you as you are now, in Australia, far from Dumaguete? What is in your studio, what are you working on this moment?

MV. I’m currently working on a small project for an upcoming event in just over a week. It is a collaborative work that will accompany the gig of an Indonesian band called Gabber Modus Operandi. For this, I have reconfigured a steel structure (police hat) that was part of my 2022 exhibition, Still Tied to a Tree. In this iteration of the work, I have bound several ceramic sculptures to the structure using string. I have also created some white panels, which my collaborator Miles Dunne will project a light and video work onto. Please see attached an image of the work in progress.

PART TWO: 16th August 2024

TG. Mark, can we go to the beginning. What sort of family did you come from? What did your parents do? were you brought up in the country or a town?

MV. I was born in Pagadian City in Zamboanga del Sur, Mindanao. I am the eldest of four children. When we were little, my father was a soldier so we moved around a lot, throughout Mindanao. Later on, both my parents became teachers.

TG. What did they teach? at school or college? and when they settled was that in Mindanao? (To which incidentally I have never been.)

MV. My mum taught grade school for many years and just retired last year. My dad taught high school and also retired two years ago. He’s now back in the reservist army.

I think I was around 7 or 8 years old when we stopped living in army base camps and settled in Pagadian City. We moved around a bit within Pagadian City, as there is a military presence in the city and several base camps. My parents stayed in Pagadian from then on, but are currently looking to move to Dumaguete City where my sisters now reside (and where I regularly visit).

TG. Where do you think of as home: Pagadian in Mindanao or Dumaguete in the Island of Negros, Visayas? Or has your army background made you restless – like Jack Reacher in Lee Child’s books – or longing for fixity? My father moved every year in his childhood because his father was a major – in the Salvation Army. I think it left him hungry for a sense of place, an unchanging home.

MV. That’s a very interesting question. In the Philippines, I now think of Dumaguete as home. I moved there when I was 17 and lived there for more than ten years. I am a bit restless, in that I don’t like to be fixed in one place for too long without travelling. But for the places that I consider home (Adelaide, Australia and Dumaguete) I like to have a base, and a space to play around. I used to have a place in Dumaguete but not anymore, and I am wanting to re-establish a studio and place to stay there.

TG. You are obviously close to your three siblings. Are they sisters or brothers? What have they gone on to do?

MV. Two sisters and one brother. Yes, we’re a pretty close family. My two sisters work from home for international companies and my brother is a mountaineer by profession. He lives in Ilo-Ilo so I don’t see him as much, but we try and organise the occasional climb together. My siblings all have their own families and children too.

TG. Do you have children?

MV. I have an 18 year old, Azul, and a 5 year old, Nailig. Azul is currently studying in Melbourne and our little one has just started school.

TG. Is Azul by an earlier relationship? Is he named Azul as in sky? Is Nailig a Gaelic or a Tagalog name?

MV. Yes, Azul is from an earlier relationship. He has lived with us in Australia since he was nine. His full name is actually Lazuli – as in the stone, lapis lazuli. Nailig is a Cebuano word, although it is very old language so not many people know it. The root word is Ilig, which means ripple or flow, therefore Nailig would actually translate as there is a ripple or there is a flow (as na is a shortening of naa, which means “there is”). It is also the name of a lake in the crater of Mt Talinis – a place in Dumaguete that I have regularly climbed since college. Anna and I met in Dumaguete so we decided on a name that had a connection to the place.

TG. What wonderful names! Is Nailig a girl or a boy? Have you and Azul become Australian citizens? This is really a question for later as is also whether having a child has affected your work. Having children certainly changed the way I think about art, life and teaching. I maybe had some effect as both the daughters have become artists!

MV. Nailig is a girl. Yes, we are both Australian citizens but are also allowed to maintain our Filipino citizenship. Yes, definitely kids have impacted my work. It has made me less transient for one thing. I now look for residencies where I can bring the kids because I don’t like to be away from my family for too long. I find being around young kids is great for creativity – they are uncarved blocks when it comes to creativity, they don’t have boundaries and inhibitions yet and so are very present and observant.

TG. My memories of when my four children started school is that you suddenly had more time but that part of their life became unknown to me. That their experience of the playground, class etc was something they could never share with their parents.

MV. That is really true when they start school. You go from knowing every part of their world to having to let go and accept that they have their own lives. When I named Azul, it was because he was like a precious stone to me. But as he grew, I realised that he wasn’t mine in the sense that I owned him. He is his own person, which I really love and admire.

I’d be interested to hear how having children changed your way of thinking too.

TG. I think being in reminded of the importance of play. and the fun of play! The need to explain things clearly – my then teenage daughter was my reader for my Conceptual Art book. If she couldn’t understand what I meant I had to make it clearer. And deeper down there is a sense of continuity: things will carry on after I kick the bucket. Kids are also very good at pricking one’s pomposity.

I think you could also add vis-à-vis children that there was a terrible sense of loss when my first marriage fell apart and my first two children moved over a hundred miles away. I carried on seeing them as much as I could but it was difficult to deal with.

MV. I agreed with everything you said about kids, about play and also continuity. And I love that your daughter helped test out your book in that way. Yes, I felt that loss you speak of when I first moved to Australia and Azul was living with my parents.

TG. Looking at the otherwise very extensive chronology in your book, the only thing listed in the first fifteen years of your life is that at the age of six you started playing chess competitively. Are you an aggressive chess player or a cool, cerebral player? Do you still play? When I look at your works which are almost always multi-part I can see a connection to the chess board with its 32 movable pieces.

MV. I think I can be both types of players… I play blitz sometimes and that is a more aggressive way of playing as you’re also chasing time. Yes, there is definitely that connection with my work. Also, there are endless possibilities with chess, which I think relates to my tendency to keep reconfiguring and repositioning works. There is also a connection between chess and my interest in space and territory and occupation.

TG. I am trying to imagine your early years. In your home were there any books on art? Were either of your parents interested in art? Did you like making things as a kid? models? Lego? etc.

MV. No Tony, no art at home. It was a struggle. But I was always drawing and making things. I was not that privileged in terms of toys when we were kids. But not having too much was probably a good thing because I had to make my own toys. Also, my grandpa was a carpenter so I spent time in his workshop.

No art books at home either, but many about military tactical formations. I didn’t read any art books until I went to university. I was studying accountancy and later on engineering, but I was more interested in art so I started reading whatever was available in the Silliman library.

But as I’ve grown older and reflected on my early years, I have realised there was art in my childhood. There was music, storytelling, performance etc. But there was certainly none of the kind of contemporary art I encountered later on: that I had to actively seek out.

TG. As a kid I was fascinated by military tactics. I once recreated the battle of Waterloo in my bedroom. I loved looking at maps of battles – all the battalions and squadrons and artillery batteries arrayed in formation. And I can see that sort of map – patterns imposed on chaos – echoing in your works too. My dream was to be a general. But as a skinny, slightly autistic kid a career in the army was never likely! Chess of course is a war game – witness the knights and castles. Do you still read books on military matters?

MV. I think we would have been friends as kids! I can clearly memorise military formations up to now. I became a Battalion Commander when I was in senior high school as part of the Citizen Army Training (CAT). It was very competitive because each high school had to participate in a tactical inspection. My dad had all the books because he was a tactical inspector for the university and sometimes in high school. But I don’t read about war or military matters anymore – I somehow dropped it but that history still comes out in my works. I love that description, “patterns imposed on chaos” – there is always a tension in my work between control and subversion, whenever I create a pattern, I then try to subvert it and vice versa.

TG. I was fascinated that in your book you included four photographs of your passing out parade as battalion commander. Should I call you Colonel Valenzuela? It was important to you?

MV. Haha, it would be Cadet Colonel but please don’t call me that! It was important to me because the military shaped my childhood in so many ways. And I almost went further down that path. And then my departure from this path to become an artist represented such a seismic shift in my life.

TG. This happened at university. You went to Silliman University in Damuguete. Was there a fine art department there? I have read in your book’s chronology that you studied accountancy and then engineering but by your second year were more interested in art and according to your chronology painting and drawings. Traditional, representational things I assume. It is indicative that you do not say in your chronology whether you actually graduated. Did you? And in Engineering? How did your parents feel about your change of direction?

MV. Hehe that is a very good pick up – no I did not graduate. My sisters still tease me for spending so many years at university and coming out with nothing, at least not with a piece of paper. I studied management in between accountancy and engineering as well! There was no fine arts course at Siliman, or the other universities in the city, at the time. Yes, I started off with very representational works, most of which now make me cringe. My parents were not happy about my change in direction. It caused a rift for a while but I understand where they were coming from. They worked hard for us and wanted us to have a good future.

TG. When did they come to terms with your errant trajectory in life?

MV. It was some years, but I think they just accepted it in the end because they realized they would never be able to stop me.