Who lives in my patch? What sort of people live in Maritime South-East Asia? (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore).

As I understand it, and it is very complex and many details are in dispute, there is a vestigial negrito population – small, dark skinned people that arrived maybe fifty thousand years ago and are called orang asli (original people) in Malaysia, Igorot in the Philippines or Papuan in East Indonesia, etc. The majority population is Austronesian – people originating from Taiwan a few thousand years ago. (2.3 % of the population of Taiwan is still Austronesian not Han – see my letter 41 from Taiwan.)

Maritime South-East Asia is a crossroads. It is where you have to sail through to go between India and China. Many people have come here to trade in the last three thousand years. They brought their cultures with them. The great Buddhist and Hindu temples of Java bear witness to the impact of the Indians who came here. Then followed Arabs, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, English, Americans, Japanese – and others. They all left traces: languages, buildings, myths, stories, and, of course, DNA. Some settled. (You have to remember that until recently this region was, with maybe the exception of Java, lightly populated. There was lots of room. As recently as 1900 when the population of the UK was 38,000,000 the population of the Philippines was only 8,000,000. Now it is over 102 million whereas that of the UK is 64.5 million. OK it is an extreme case!)

The most important group to settle was the Chinese. Between sixty and eighty per cent of overseas Chinese live in South-East Asia. (The variance in figures follows from including or not including those who over the years have intermarried and either assimilated, or created a mixed mestizo culture – normally called peranakan here.) With assimilation policies Chinese names have been discarded so artists Agus Suwage (Indonesia) and Manit Srimanichpoom (Thailand), for example, are all of Chinese ethnicity. You cannot understand the art world of South-East Asia without a sense of their presence. Also, importantly, they constitute the majority of the collectors.

But it is the Japanese I want to talk about. Their presence is not so obvious – even though they are the largest ex pat. population in Singapore.

When I first went to Tokyo, I asked an English friend who had lived there what I should go and see. She told me I should stand on the street corner and just look at people and see how weird they were. Well, I have to admit she had a point, but let’s use the word “different” not “weird”. How we regard the Japanese is often a personal thing. That’s to do with history and how we react to a culture that was and still is very different from elsewhere.

Whilst my uncles were fighting at Alamein and Arnhem and Beirut, eventually coming back traumatised and angry, my father was refused permission to go to front line as a padre. He continued his work as a curate in the Isle of Portland. His parish included a large prison where he met German and Japanese prisoners. After the war one Japanese soldier he had befriended sent back a print by way of thanks for the companionship he had given in bad times.

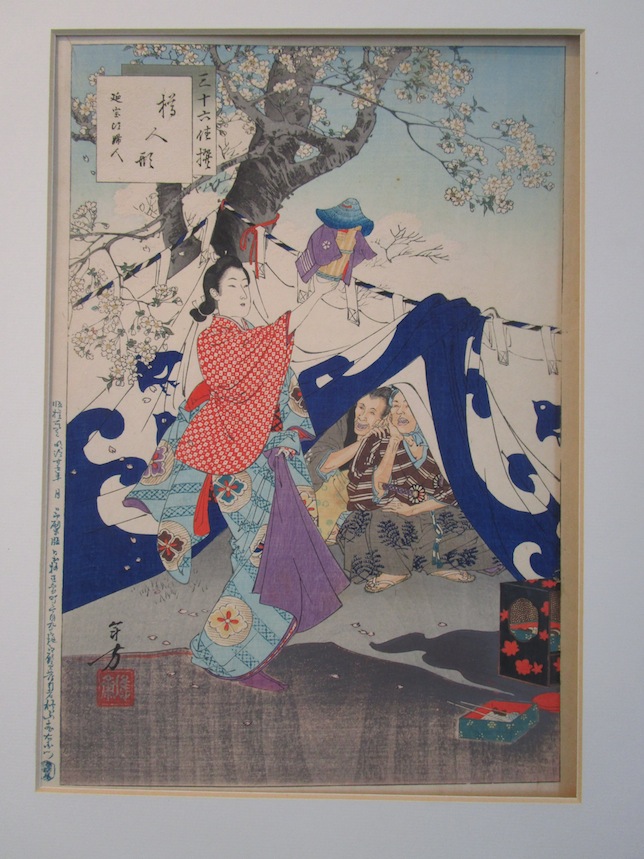

It hung on the wall of my bedroom as a child. It was double sided: on one side some elegant women cross a bridge; on the other a scary looking soldier prepares to fire an arrow. As a result, I grew up thinking that Japanese women were beautiful and Japanese men were ferocious. When I actually met Japanese people, I found the first assumption was true, but the second was not.

Sadly, I no longer have the print: my indigent elder brother sold it, but I’d love to find it again one day. Just recently I bought two Japanese prints – they are not expensive if you know where to look – and I tapped straight back into that mood.

The delicacy, the asymmetry and that very particular colour sense. Even now in the age of manga it is still there. Those wonderful Studio Ghibli films have it. Japanese art is almost always very recognizably very Japanese. Or remember if you saw it Sugimoto’s project at the 2015 Venice Biennale: glass tea house Mondrian. It is very contemporary but yet so Japanese: if they had time travelled to this summer Toshikata and Kunisada would have recognized a fellow countryman’s work.

I think it was my favourite thing in Venice: so precise, so poetic, so thoughtful. Even the attendant was in costume! I enjoyed sitting there in peace, at least until a group of Italians entered and started talking to the attendant at great speed and very loudly. Oh dear, there’s another national stereotype spilling out!

If you ask many artists in my patch where they would most like to go they often say, “Japan”. It fascinates them as much as it does us. In many ways the Japanese are as different from them as they are from us Europeans. Historically, there are mixed feelings: the war-time atrocities balanced against the prestige of being the first Asian country to both industrialise and defeat a Western power (Russia in 1905).

This is just one of many reasons to not think of Asia as a single uniform continent or culture. In a way it would be better if this word “Asia” had never existed and we thought rather of six sub continents or mega-cultures: the Middle East, Central Asia, the Indian sub-continent, South-East Asia, the Chinese world and Japan, which is a nation uniquely sui generis.

Have a good Tuesday,

Tony