Wawi Navarroza in conversation with Tony Godfrey

Interviewed 3rd January 2024

TG: Wawi, next week you’re traveling to New York for your show. What’s in it?

Wawi: My solo show is entitled “The Other Shore”. It’s a comprehensive collection bookending 2019 and 2023. It spans those years, when a lot of things were going on in my life.

TG: Yes, Marriage, Istanbul, Childbirth, the Pandemic, Separation, returning to Manila. It’s not exactly a retrospective, more, a selection of recent works.

Wawi: It’s a specific arc of the work.

TG: Which is the most recent work?

Wawi: Rosas Pandan. Volviendo.

53 x 40 in / 134.60 x 101.60 cm

Archival pigment ink on Hahnemühle Photo Lustre cold-mounted on acid-free aluminum.

Artist frame with blue fabric, green lace and artisanal patadyong textile wrapped on wooden mat board and glazed, colored frame

TG: My instant response is, yes, it’s you, it’s a self-portrait again. And then I notice these strange things on your shoulders. And the magic word “Imelda Marcos” flies to mind because she was notorious for wearing such enormous, puffed-up shoulder pads.

Wawi: It’s a traditional Filipino dress called a terno. And it features a prominent butterfly sleeve. That was what Imelda wore often, true. But this piece is not to do with her. It’s more of a bigger recall on the historical and symbolic Filipiniana dress, the terno. It’s been a part of our larger history, from the colonial to the modern; this dress has seen it all and evolved with the times. Of course, a lot of people have seen it in vintage photos, and also popular in beauty pageants and galas. Anyhow, there are a lot of layers to looking at my tableaus. I can speak about it through different doors. Or, put another way, there are many doorways through which you could enter. But I think the easiest to go through is the material. More and more, I realize that in my work there’s a lot of material history. More and more I am involved in the history of material culture, and all its meaningful tangents. In my tableaux, there’s a blend of the artisanal and also commercial stuff that I found in markets.

TG: As someone who’s lived in the Philippines for twelve or so years, I recognize firstly, in the back, behind the black boots, plastic lemonade bottles that have been cut up to make flowers. Whenever you got in a taxi, you used to see one of these on the dashboard. It was like a big thing seven or eight years ago. You saw them everywhere.

Wawi: It was this particularly iridescent neon green that was from the bottle of a specific soft drink and energy drink. They were upcycled to look like plants, to look like vines, or decorative things. In one of my other work some years ago, I had one or two of them that I bought from road-side sellers that I just happened to come across. But this piece (Rosas Pandan) has a profusion of them. Out of curiosity I tried to find a person who was actually making them. And I found a seventy-year-old man who was doing this. I asked him, “where did you learn how to do this?” He was laughing as he said, “you know, people think I just came out of jail because it’s people who are in jail who do these things”. But he learned it from a friend of his. So, there’s a kind of craft and storytelling here. Every material that I use, there’s another layer of story. I just bring them all into the tableau. It’s framing the whole scene here in this piece, almost as if it’s a garden – of recycled up-cycled plastic.

TG: This is a sort of contemporary folk art and he is really good at it. I like that he has added blue, red and violet plastic flowers. There are so many things here! We could talk about this for several hours.

Wawi: That’s the truth. Sometimes when people ask me to talk about my work, it can be very detailed or just about the colours.

TG: When I saw your 2022 show in London (As Wild as We Come) what struck me was that these new works were very much about colour. However, you are absolutely correct. They’re also full of both familiar and strange objects, some of which are very specifically Filipino or Pinoy.

Wawi: And some of them are also from other places. Can I just show you a few of the references for this work? Anyway, the other day I saw an interview with Hiroshi Sugimoto and he said he never hunts for the images but it comes to him, in his mind. Being photographers, a lot of people think we have to hunt for these images, as if to capture them. To capture something, to document it. But with my process, I never hunt in that way. I actually wait for it to arrive as fragments of images like a vision, and then I combine them.

TG: OK. Do you always photograph actual images and actual things, or do you sometimes take things off the Internet?

Wawi: Never from the Internet.

TG: At this moment I’m sitting in what you call your micro studio, a room that is about twenty by twenty feet, and it’s clearly set up for a photograph at the beach. The beach itself, and the sea, is a back-drop one printed on a big cloth, but there’s also a real dress with big, big shoulder pads hanging nearby waiting for you or someone else to wear.

Wawi: Yes, this is where it all happens. Where the whole cargo of visual culture can come. I’m very aware of that lineage of images. I’m also aware of art history and also of local, vernacular, image-related things, be they postcards or whatever. About Rosas Pandan, I was so surprised to get the sudden impulse to work on this because it was familiar but I didn’t pay attention for years. I thought where did I see that? In my head? It felt as if it was there, though I wasn’t thinking about it actively, it was happening through me. And only after I finished the making the piece, it connected to another image — this vintage photo from the American period.

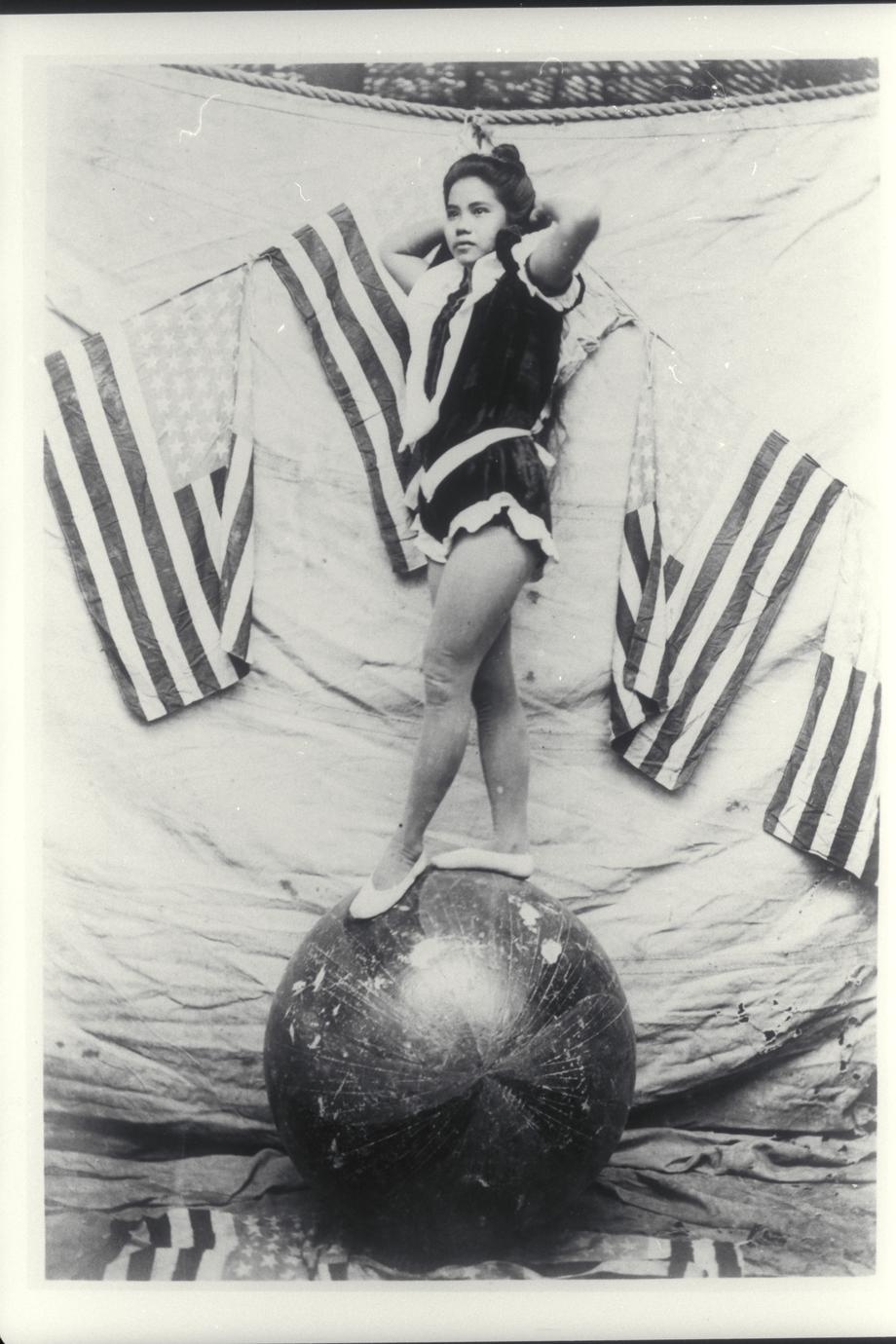

Native female circus performer, 1910-1930

Native female circus performer, 1910-1930

TG: It does look sort of familiar.

Wawi: Then it comes even more alive if you’re a Filipino; it’s something from another layer in our collective past. Another thing that I wanted to bring attention to is the actual title Rosas Pandan. It’s from a folk song — a Visayan folk song that my mom knew. Of course, when we were all growing up, we all thought that folk songs were a bit of a corny thing but now more and more in my practice, I’m reclaiming what we were made to be ashamed about.

TG: Is it in Visayan?

Wawi: It’s in Visayan Cebuano which I understand it perfectly. It has a marching beat, so you can imagine what it sounds like when they play it during the parades in the provinces. And it says that Rosas Pandan was this beauty from the bukid, from the mountains, or from a far-flung place. She comes to town to attend the fiesta; she sings an ancient song and dances the balitaw. And then, because she’s beautiful, every boy and man at that fiesta is just drooling – literally drooling (“nagtabisay ang laway”). To me, it was significant that she’s a probinsyana – from the province. And the fascinating discovery is that this song is famously sung in chorale performances all over the world!

TG: In Visayan?

Wawi: Yes, in Visayan. From Moscow to Budapest, to Kuala Lumpur, to Seoul, to Sydney, to Utah…everywhere they’re singing this song in Filipino dialect. So, in effect, the probinsyana has quite gotten around the world. She’s a transnational. She’s been out in the world singing her ancient song. Loosely speaking, it’s a story about being an artist and being out in the world. Also, this image is about me returning home to the Philippines. But somehow the viewer can’t tell if she’s leaving or coming back. There’s that duality in my work that’s always present.

TG: Did you came from Visayas?

Wawi: My parents are from Leyte. Where Magellan landed. They moved to Manila to start their careers. I was born here in Manila.

TG: But they brought you up in your house speaking Visayan?

Wawi: They did to one another, but as a family we spoke Tagalog. I learned English in school like most Filipinos. I went to school then college in Manila – De La Salle University – to study communication arts. I acquired Spanish and other languages through moving a lot like a gypsy.

TG: What did your parents do?

Wawi: My dad’s a mechanical engineer, and my mother is an accountant. They built an industrial business from humble beginnings and made it grow. I’m quite proud of them.

TG: Like almost all Filipino artists you come from a middle-class family

Wawi: My family is earnest and pragmatic and pretty much had nothing to do with the arts except for singing. Actually, my mom and I have been singing together since I was a kid. Broadway show tunes, Barbra Streisand, Shirley Bassey, you name it…

TG: You used to be the singer in a band? Are you still in that band?

Wawi: Yes. We never disbanded. Music and performing was a huge part of my childhood. Then I got into rock music, post-punk, art rock… I wrote some of the lyrics. We have records out and actually pressing vinyl this year.

TG: Does your band have anything on YouTube?

Wawi: A lot. It’s like a secret that could easily be found. The name of the band is… (She winks scretively.)

TG: How come you went to study Communication Arts, not Fine Arts?

Wawi: I was into writing. I knew how to write, and that was my first big thing. I have loved literature since I was a teenager. I read a lot of books. I love libraries. I go in and out of worlds with literature. I went into communication arts, which is media studies because that was as much about writing as visual stuff. Possibly I felt kind of different about it because it (media studies) was to me an image-based world. And then I guess it’s just the way of destiny, my grandfather was a photographer and plus my mentor was Judy Sibayan who is a conceptual artist related to Roberto Chabet.[1] So in a way I was getting a “Chabet” art school education, secretly, even though I was not at UP. [University of the Philippines, Manila where Chabet taught.] I was divorced from all of that. But I was reading art theory. This was not usual for communication arts! It was the gift of having Judy Sibayan as a mentor that I was reading Susan Sontag, that I was exposed to the work of Diane Arbus, that I was exposed to the Pictures Generation, Cindy Sherman, things like that.

TG: I wanted to go back to an image made in 2007, a self-portrait. But presumably you made a lot of stuff before that.

16 x 24 in / 40.64 x 60.96 cm

Monochrome film capture with hand and chemical manipulation on negative emulsion, printed with archival pigment ink on museum-grade fine art paper

Wawi: Yes! Actually, ever since I was in school, I did my exercises with self-portraits and darkroom work. It has always been that way because, I guess, of the reading and the writing. I’m good being with myself and, also, I was kind of shy to subject others to doing something. I didn’t and don’t want to limit them or limit myself to do something that they won’t probably like. And my parent’s house was rather far off and isolated. It was just my natural way. Even at seventeen years old I was already doing it.

TG: How old were you in 2007?

Wawi: Twenty-six. This time was the cusp of digital and analogue, if you remember. Since I did my thesis in 2002, I always wanted to do something with dark room photography that’s not just about “capturing” the image. I wanted to intervene at every stage of the process and so I developed my self-styled technique where I cooked the negatives and controlled/arrested the obliteration of the photographic image on the gelatine emulsion. I was a mad scientist.

TG: This also looks like a Victorian photograph. An albumen print or from a paper negative, all that wobbliness at the edges.

Wawi: Yes, you’re right. I was really into pictorialist photography, early photography, and alternative older processes. I didn’t want to be a photographer, but an artist making photos. Not just taking it. And that’s remained the case. I’ve tried to kind of step away from that. There’s a period in my practice where I tried to deliberately remove myself from that. But then I circled back in and I realized that was really what is in my DNA then and today.

TG: Obviously, the big difference from what came subsequently is that it is black and white. It’s also very, very romantic. Your work subsequently has been more double edged: maybe romantic, maybe gothic, but also self-aware, as though you’re always standing in there, but also standing back, looking from both in and from the outside.

Wawi: I like that you say that, because instead of fighting it, I just embraced it. I’m really like that. I’m always in between worlds. Yes, it’s romantic in the sense that I felt that there was a world that had to be depicted in form. But it’s weird because a photo has to be created in a space, right? And you cannot just imagine it and put paint on canvas. So somehow that’s how I did it.

TG: Many of your photographs are about being in a room. Obviously, they are studio photographs. They’re in made-up environments, but they also connect to that Virginia Woolf concern with having a room of one’s own. That is persistent in your work, always has been.

Wawi: Yes, even though the rooms may somehow seem transient, and even though the setup could be done in any room. Now I come to think of it the room in Letters Unsent looks like a room by Remedios Varo. I was so gravitated to her work last year.

30.5 x 48 in / 77.47 x 121.92 cm

Lambda Durst C-Prin

This image, the Frida one, is from the same year, 2007. In the same year you see the shift, right? Because that was when I said, “OK, the dark room will stop!” And then I embraced full digital. This is my first project – one of ten photos about my conversation with Frida for her centennial – that had to do with full colour, full digital. It was totally night and day for me, but with the same sensibility.

TG: I think the black and white photograph is very theatrical, but this is consciously theatrical. It’s consciously, obviously staged. Did you have to do any manipulation or did you get the children and the dog to stand still at the same time?

Wawi: Yes, I did! Everything was in-camera at one go. Yes, even the dripping blood and the tilt to that table so the perspective could change.

TG: How long did it take to set up?

Wawi: A day or more. I would call it a studio collage, a very in-situ collaging of different things, all together at the same moment.

TG: This now seems like a very early work. But your work flows from this sort of gathered-together image.

Wawi: Looking at this early work, my current ones have retained that kind of innocence because I always work in a very DIY way – just myself and just sometimes a few people I know working with me on my set. Everything there is my own decision.

40 x 60 in / 101.6 x 152.4 cm,

archival pigment print

TG: After the storm. On the one hand, it looks a bit like what you do when you leave a house, cover all the furniture with dustsheets, on the other hand It looks like a sort of minimal sculpture. It is also like a ghost.

Wawi: And it’s actually very silent, but something is hanging up in the air. The context of this exhibition was about volcanic forces and destruction, architecture, the home, the studio. The destruction of my studio in 2011 by a super typhoon. The debris one imagines under that fabric gives a kind of kinetic weight to the work. It’s very light, and it’s very sculptural in a sense, but there’s something that’s the hidden part there.

TG: Did you actually show this as a sculpture or this was just a set up?

Wawi: No, this was more of an in-situ documentation. But the fabric that I’ve used there has also been the same fabric that I used to cover the volcano. So there was almost a performative aspect when it came to the fabric. It’s the same white fabric that I used in the piece “In A Moment We’re Almost Pure” to cover the lava rocks, the volcano which is a strong symbol of that destructive part of nature. And then I put it back over the remains of the studio, as it were. And it gave shape to it. I was asking, how do you define things? By means of covering and erasure. In a way, absence and presence together.

TG. It was the year after this (2011) when we first met. At that time, I had an ongoing project where I photographed each artist I met up with and then asked them to photograph me. I wish I had carried on with that project. Maybe I should start again!

Wawi: Doesn’t she look like this ancient mosaic found in a dig at Zeugma, Gazantiep, Anatolia?

TG: Yes! I must search for my ancient doppelganger too!

A year later, you did something similar to After the Storm, but for real.

gallery installation: variable size

photograph: 32 x 48 in / 81.28 x 121.92 cm

archival pigment print

Wawi: Everything in my practice has been a call and response, from a period of chaos and then a return to build something again, like the crests and troughs of a cycle. This one came after Spain, when I lost everything, even the digital files, and I had a solo show to do.

TG: Was it shown in Spain?

Wawi: No, this was my homecoming show. I didn’t have anything to show, but I had this sort of a map. I had this kind of matrix or something to build to start with.

TG: And this photograph is from a book project or rather, a project that ended with a book of over 300 pages and many, many images. (Ultramar Pt II: Hunt and Gather, Terraria, Manila, 2014)

32 x 48 in / 81.28 x 121.92 cm

archival pigment print

Wawi: Yes, it ended as a book project, but it was a larger process, in fact, involving other people. This was made after returning from Spain, when I had to rethink again what my relationship to my practice in photography and art was, because I lost everything.

TG: How long had you been in Spain?

Wawi: Two years for Masters. And a decade if you count coming back and forth after that.

TG: And you lost everything?

Wawi: Yes. When I was finishing my Masters, I lost all my digital archive. There is this gap of 2010-2012, where there is no, or very little surviving work. I had to start again somewhere. Having been working with big landscapes I re-started with something that is smaller, something as intimate as the Terrariums.

TG: And all these plants were collected in Manila?

Wawi: Yes, collected by different people. People who wanted to take part in the projects sent samples of weeds, plants, soil and rocks that were taken from different parts of the city. Everything was documented.

TG: Something struck me when I lived in Sampaloc, part of Northern Manila. It’s not a slum, but a very overcrowded quarter of the city. There was no public park, no green recreational space but there were incredible amounts of people who compensated by growing plants in old cans and jars, placed on the sidewalk outside their front door. There was a desperate desire to create a bit of green nature. This I think connects to your project.

Wawi: The book is fascinating because it also carries with it some texts that the contributors wrote about where they got the plants and what they were thinking. Some of them encountered these plants in their daily commute, in the cracks in between the concrete, in a train station. Some of them were taken from buildings and some of them from the backyard. You get that diversity of urban life and nature in Manila. And it was all mapped out in the book. Eventually it became more of a psycho-geographic exercise. And it’s beautiful in the sense of a microhistory. It was a very small output, just the terrariums in jars. But it also led us to talk about the historical places, what happened there, and what it meant for the participants personally. People may have thought these terrariums were a decorative thing. But we were also talking about ecologies, we were talking about migration – the plants don’t move themselves. There was the history of the scientific revolution, when they were taking all these tropical plants to greenhouses in Europe – and here! One of the problems here is invasive plants. brought by the Spanish and the Americans.

TG: Can we talk about this image from 2016. I want to live a thousand more years.

50 x 40 in / 127 x 101.6 cm

archival pigment print on Hahnemühle paper, cold-mounted on acid-free aluminum

The title from this comes from a famous poem by the revolutionary Indonesian poet Chairil Anwar (1922-1949). I think an American or an Englishman might ask, “Why is she quoting an Indonesian poet?” I think everyone in South-east Asia does want to have some sense of kinship within the region. Between the Philippines and Indonesia especially, there’s a very real sense that these are two groups of related people. As one Indonesian said to a Filipino, “you’re like us, but you don’t speak the right language”.

Wawi: Yes, but we borrow words from each other. There’s a lot of non-documented relations between the pan Asian countries. Actually, I just started reading a book titled Asian Place, Filipino Nation.[2] It chronicles the relationship within Southeast Asian countries before and during the colonization period. The Indonesian connection with this piece was that I was doing a residency in Bali when it happened. I got dengue there. A tropical disease.

TG: A really bad one, mosquito borne, some people die from it.

Wawi: It’s debilitating. I was not able to walk after that for a month. That’s why in this portrait I have a crutch. It was really painful. Even after surviving it, it really takes a toll on your nerves. I was hospitalized for about two weeks. Ironically, I got dengue because I was researching plants in Bali. Remember the terrariums? I was into plants. I was investigating the tropical lush things. And then when I was hospitalized, they said, “there’s no cure for dengue”. But my Balinese friends would bring plants that were helpful for dengue. They’re giving me jamu, the roots, and a weed, tawatawa, that turns out to be really helpful in getting your platelets up again. I was drinking different herbal remedies that came from plants. It became that whole thing of cures and diseases, life and death conjoined. And my work changed after that. It just became colourful. I think I would say 2016 was the zero point that changed my work. It’s colourful, but in a different way to let’s say, the Frida Kahlo piece. Things are being chosen for their colour; the composition is to do with colour. Although the colour is always connected to object or a reproduction or a photograph, it somehow becomes very much colour focused.

There’s the Polychrome, which we don’t speak about, but is a birthright for Asian art from Anatolia to India to China, Japan, every country that’s in the greater Asia. We all have a heritage of colour. The polychrome is there. There’s this risk of things being called “kitsch” because of the polychrome. But I’m using it to underline a specific thing.

TG: Polychrome is also very connected in my mind to the sort of Catholicism you have here which came from Spain through Mexico. Also, often when I visit people’s house in the Philippines, I often find an incredible collection, miscellany or clutter of images, objects and colours.

Wawi: Yes. I think that colour also takes us back to that connection to other places, Mexico and even Africa. You see it in the fabrics.

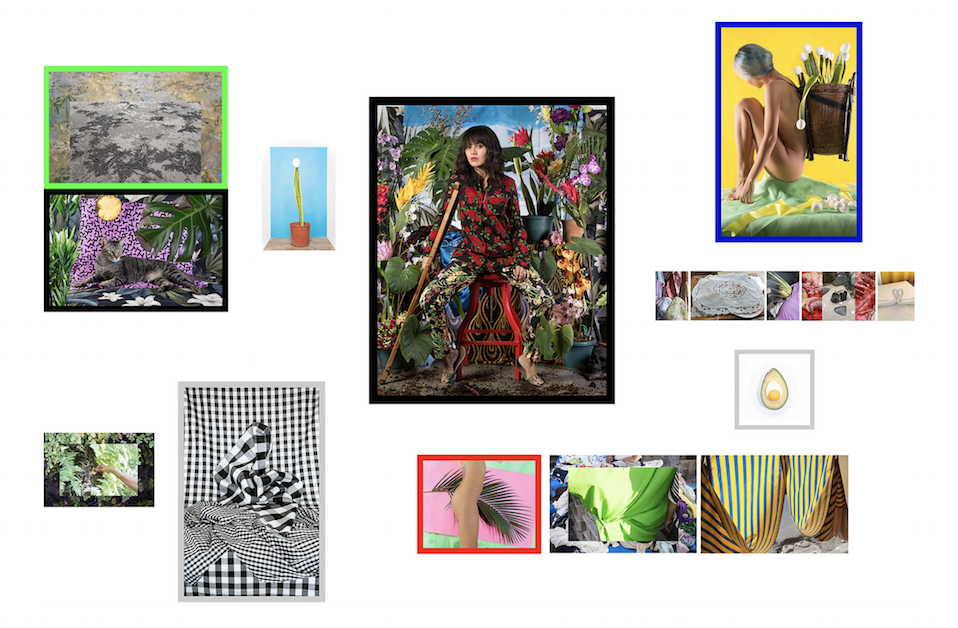

TG: Yeah. I thought we should also show the photograph in the context of the whole series. Looking at individual photographs it is easy to forget you often work in series. We showed this in the show I curated in Slovakia.[3]

dimensions variable – to fit on a wall

Wawi: This is neotropical tapestry with a K. Tropikal. This is the work I made during my residency in Bali and also in response to the great Balinese artist Murni. Some of the pieces here are appropriations of her work, translated from painting to photography. My works and her works combined, plus Balinese fabrics, which is a lot to play with! I’ve become quite a collector: wherever I go, the market is where I first go – in Bangladesh, Cambodia, even in Davao in Mindanao. In Bali, they have a whole market scene. And there’s another layer to Murni: she used to work in a garment factory, and that’s how she came up with those weird colour combinations in her work. You might think, where did that come from? Because it’s not your usual harmony in the colour wheel. So that was something that really stuck with me, and I still apply it now when I combine colours in my tableaux.

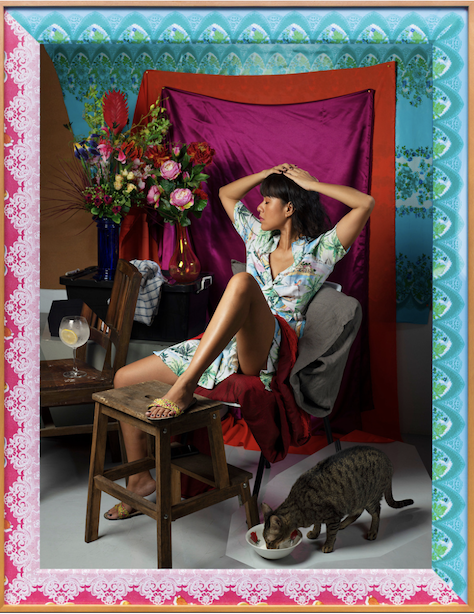

53.30 x 40in / 135.38 x 101.60 cm

archival pigment print on Hahnemühle paper, cold-mounted on acid-free aluminum, with artistʼs exhibition frame i.e. wrapped fabric on custom-tinted double wood frame

TG: It was very brave of you to work with Balthus because he has such a controversial reputation. A bad reputation. Some people assume, incorrectly, that he’s some sort of paedophile.

Wawi: I would never know. All the debates are valid. When I did this, it was to put a mirror to that. I was making it fully aware of art history, and also fully aware of how Western eyes see Southeast Asian women as objects of sexual desire and all of that comes with it.

TG: In later years, he was married to a Japanese woman.

Wawi: I didn’t know that. Reacting to a specific work in art history kind of bobs up and down in my career, as one-off pieces. When I’m traveling, I go to museums, and then I see the actual pieces and I have more of an immediate reaction to it.

TG: Balthus is problematic, nevertheless in many ways he’s actually a great artist: he produces many extraordinary images, he has an incredible sense of surface. I’d be fascinated to see you take him on as a project as you did with the Frida Kahlo. He is not, as Kahlo is, a paradigmatic figure for a South-east Asian.[4]

Wawi: I think she’s like a best friend to me – Frida. Anyway, about Balthus, I read afterwards that the Met was petitioned to remove that Balthus painting from their walls, but the decision was to keep it. In Singapore they showed this (Balthus) work of mine at the 2022 exhibition Living Pictures: Photography in South-east Asia.[5] By doing something like this I was hoping that it would create other conversations. It’s not meant to be a dead end.

TG: He is the great painter of cats.

Wawi: In my work that’s my cat Hunter. You visited my studio at that time, 2019, we had long conversations.

TG: Yes, we had a very long and interesting conversation about the tropical gothic which I wrote up in my Tuesday in the Tropics newsletter.[6] It is sort of still your theme, isn’t it?

Wawi: Yes. It is the special sauce and the red thread that runs through it all. Then when I lived in Istanbul I also realized that I am a magpie when it comes to visual culture. I have amassed this new fascination for the ancient world, the Byzantine, the Mesopotamian.

TG: This was 2020 and you gave birth, correct.

Wawi: I gave birth in the middle of the pandemic here in Manila, moved 5 times in the city, and then moved to Istanbul for two years. There it was like cave time. It was, to me, a cave era. I disappeared.

TG: You were in a marriage, which didn’t go so well.

Wawi: Not a marriage but the partnership didn’t work, there was rupture. There was transformation. I was a creator as an artist, and now I’m also a creator as a mother. Two creators. And here, in these portals, I was visualizing them talking:

44.3 x 40.5in / 117 x 101 cm

archival pigment ink on Hahnemühle Photo Lustre mounted on dibond / artist frame with wooden mat board and glazed, colored frame

TG: That’s your son?

Wawi: That’s my son.

TG: Your photography has often been to do with self-portraiture. Will you use your son more and more as part of that process?

Wawi: I’m not sure yet, but right now, he’s not into photos.

TG: You don’t use self-portraiture in a confessional way. It’s not overtly autobiographical.

Wawi: No. It’s more an allegory for other women to contemplate on. I just used myself as some sort of a medium and channel to communicate, because I believe that women reflect on women through other women. There is always that lineage of women, mothers, daughters. It just flows through that river of time. It’s difficult for me to say it without sounding so mystical. But in a way since having accessed that threshold of motherhood, I got tapped into that eternal passage of time.

As an artist, you get doubled up. One writer described my work as “Janus-faced” because one is looking here, one in another direction – quite overtly in this image.

TG: The patterns in the back at the right, the blue and red flowers, I assume come from Iznik tiles. When I went to Istanbul I was knocked out by those tiles in the old buildings.

Wawi: Yes, Iznik tiles. They’re beautiful. Old ones are especially exquisite. Similar to the ornaments and patterns, I’m using what they call “women’s art” in my tableaux; things like lace, embroidery, fabrics, textile weaving. These are all in the domain of the women as seers. The first artists in the Philippines were actually weavers. I’m rethinking and repositioning all that has been relegated to the side as not belonging to the so-called sophisticated world of high art.

TG: Why do you have eggs all over the floor in this picture?

Wawi: Actually, there’s an Easter egg hunt all over my work.

TG: The egg is an image of maternity, but they also that strange notion of image of purity. I am thinking of that curious painting by Piero with the suspended egg.

Wawi: Or the cosmic egg or the egg as a zero, or the egg as a possibility. I like that shape. I like that symbolism. It actually appeared to me in a dream, so I have no way to explain it, but to say, it is a dream.

TG: Do many of your images and ideas come out of dreams?

Wawi: Not all of them but some are very deliberate. When it said in my dream there are eggs in the four corners, then I had to make the image with eggs in the four corners. And then sometimes it’s the title, sometimes it’s a particular colour that comes from a dream. I can’t explain it, but it comes in this fragmented way, and then I put them together. Yeah. So that’s how it happens.

TG: What do you want as your final image?

Wawi: This one. One of only two works I made in 2023 because I was busy moving.

31 x 24 in / 78.70 x 61 cmArchival pigment ink on Hahnemühle Photo Lustre cold-mounted on acid-free aluminum . Artist frame with wrapped fabric on wooden mat board and glazed, colored frame

Those two stones, one is from Galicia, Spain and its Atlantic coast. The white marble one is from here, from the Pacific. This is a colour experience of pink, purple, red, and white and black. Places where I lived. I found it at the tip of the northwest of Spain, in Galicia. So it’s formed by the Atlantic. It’s your sea, Tony, the one that spreads to England. A cold fairy-tale sea, that sea. And then this is from the tropical Pacific. This is marble from Romblon and curiously shaped like a heart. I’ve kept them. It’s a strong image. That’s why I didn’t add anything more.

TG: It is a simple, strong image. In that it reminds me of your strangely haunting Self Portrait with Bricks from 2012

.

Self Portrait with Bricks (Autorretratro con ladrillos), 2012

41.34 x 27.56 in / 105 x 70 cm

archival pigment print on Hahnemühle paper, cold-mounted on acid-free aluminum

Wawi: This is from when I lost everything. Yes, the bricks. It’s actually from an anecdote, when I was living in that part of Spain, where the wind is crazy coming from the mountain – tramontana.

I was struggling to walk ‘cause the wind was blowing strongly. And then this old lady passing by told me in Spanish, “Hey, little girl, you have to put bricks in your pockets if you don’t want to fly away”. And I said, vale! (“ok”) And when later, I found I had lost everything, I said, “I need those bricks to build again. I will start to build from these two bricks. I have nothing else, just these two bricks and that story.”

I said, “OK”. I am all in white. I had just turned 33, so I felt like Jesus. It’s a place that is all white. Everything is white. The white washed walls of Spain. There’s a white period in my work, when there’s a flash of white, as in After the Storm. It’s cleaning up time. And then there’s another flash of white with the marble work that came after the fire in my studio. There’s my studio destroyed by a super typhoon in 2011, and then the loss of all my work in 2012, and then the studio destroyed by fire in 2016. That’s life happening. It is almost as if making self-portraits as a way of saying “I’m still alive!” Right? Like I’m a cat and I have 1000 lives.

TG: Nine. Cats only get nine lives. Don’t get greedy.

Wawi: Haha. Okay. Nine lives. I hope I don’t run out! Not to mention, I was quite sick with autoimmune diseases when I made “As Wild As We Come” (2022). But look here we are! Women have 1000 lives. I healed myself. I transfigured. I still smile. Something about art makes me continue. So that’s quite good. Okay, thank you, Tony. Let’s stop here.

Wawi’s exhibition The Other Shore is at Silverlens Gallery, New York 11th January to 2nd March 2024

Her website http://wawinavarroza.com has an extensive selection of her past work, images and texts.

-

Roberto Chabet (1937-2013) was a conceptual artist who as a teacher had a profound effect on two younger generation of artists. ↑

-

Nicole Cuunjieng Aboitiz, Asian Place, Filipino Nation: A Global Intellectual History of the Philippine Revolution, 1887-1912, Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2021 ↑

-

Far Away but strangely familiar: twenty-three artist from the Philippines, Danubiana Museum, Slovakia, 2019. Parts of the exhibition Catalogue are available at Attalksea.com ↑

-

Her mestizo ancestry and anti-colonialism, her concern with indigenous culture, the romance of her life have an especial appeal to many artists of the region. Filipina Geraldine Javier and Indonesian Agus Suwage are two of many artists who have referenced her in their work. ↑

-

At the National Gallery Singapore, There is a substantial catalogue for this exhibition, ↑

-

Tuesday in the Tropics 144, 22nd May 2019 at Arttalksea.com ↑